The U.S. Navy is looking into whether it might be feasible to install a so-called “hard-kill” self-defense system to physically shoot down incoming missiles that could go onto various transport, tanker, and other combat support aircraft, or equip an entirely new unmanned escort platform. The contracting notice comes as the U.S. military as a whole is becoming increasingly concerned about the vulnerability of these assets in any future high-end conflict, especially as potential opponents, such as Russia and China, continue to develop and field more capable air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles, as well as associated sensors.

On May 3, 2018, Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) announced it was interested in what it calls the Hard Kill Self Protection Countermeasure System (HKSPCS) in a request for information it issued on the U.S. government’s main contracting website, FedBizOpps. At present, the Navy has no formal plans to purchase any such equipment and the notice only provides basic parameters, asking interested contractors to submit proposals that would meet those requirements.

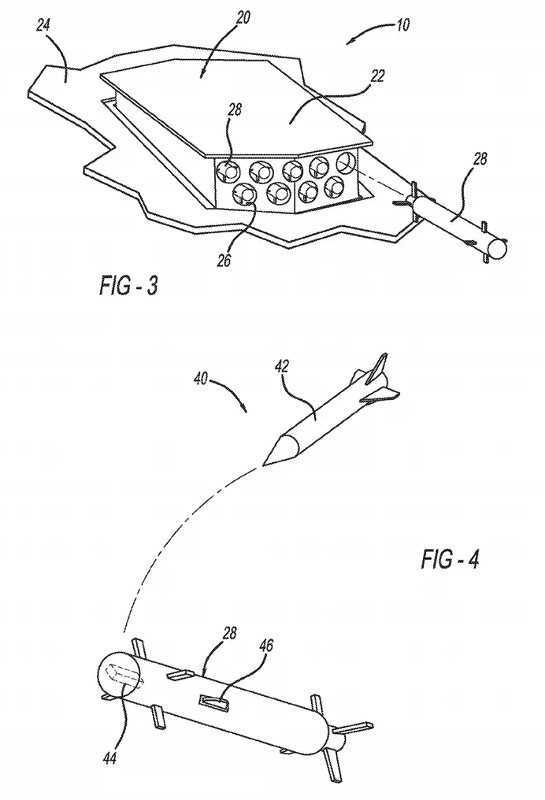

The notice says that the HKSPCS could serve as an “alternative and/or adjunct to more conventional electronic self-protection solutions.” The rudimentary requirements do not specify the exact means of interception, but the most likely concept would be a salvo of some form of miniature, highly maneuverable interceptor missile. Northrop Grumman patented a system matching that basic description in 2017 and we did a large feature on it and its potential applications.

Since modern air-to-air and surface-to-air missiles use proximity fuzes and fragmentation warheads to shoot down aircraft, other systems that employ an explosive charge or burst of shrapnel, similar to the active protection systems on ground vehicles, would be largely ineffective for aerial use. On top of that, the debris from those close-in detonations near the host platform could easily damage sensitive equipment or clog air and engine intakes, or worse, with potentially disastrous results.

However, the same launcher could eventually fire various other types of munitions as well, just as existing countermeasures dispensers can already release both flares and chaff. Active electronic warfare expendable decoys, such as Leornado’s BriteCloud, are already steadily gaining popularity around the world.

NAVAIR says it wants the HKSPCS concepts that will be able to have enough shots to successfully defeat at least four to 10 incoming missiles. The systems could either be internal to the aircraft or an external pod that will work with any standard BRU-32 bomb rack.

The Navy wants an internal system to weigh 2,300 pounds or less, while the podded arrangement could be anywhere from 850 to nearly 2,890 pounds. The external type would need to be less than 210 inches long and have a maximum diameter of just over 31 inches.

The request for information specially says the platforms that NAVAIR is interested in installing the added defenses on include derivatives of Lockheed Martin C-130 family, the McDonnell Douglas DC-10, and Boeing’s 707, 737, 757, and 767. This would effectively encompass almost all of the U.S. military’s large, airliner-sized combat support aircraft, not simply those in Navy service. The Air Force, for example, is the only operator of a DC-10-based platform, the KC-10 tanker.

This broad requirement would also include a slew of other aircraft, such as, but not limited to KC-135 tankers, RC-135 spy planes, E-6B airborne command and posts, C-32 and C-40 personnel transports, P-8 maritime patrol aircraft, and any of the myriad variants of the C-130 in use across the services. By naming the 767, the Navy also appears to be considering a system that would work with the Air Force’s forthcoming KC-46A tanker, as well as any future combat support aircraft that might emerge based on that design.

A common, U.S. military-wide system would help reduce training and logistics requirements and allow for larger, block buys that could help push down the unit costs. The U.S. Navy is already familiar with this model when it comes to aircraft self-protection systems, having acted as the lead service when it had come to the development and procurement of directional infrared countermeasures (DIRCM) systems in use across the services.

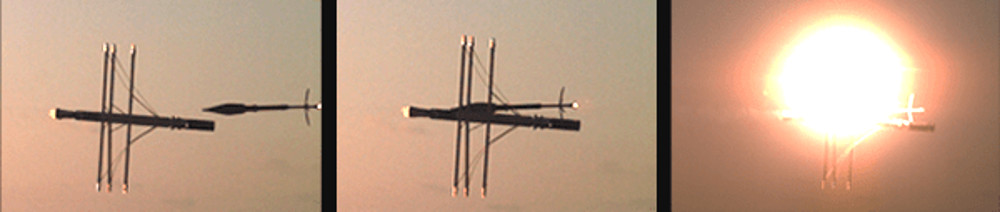

The video below shows a directional infrared countermeasure system deflecting a missile during a test.

Those are soft-kill active defense systems that use a laser to confuse and disrupt the seekers on infrared missiles. Many of the aircraft NAVAIR mentions in its contracting notice question already have DIRCM defenses.

A large number of American allies and partners use military aircraft based on these same platforms, which could open up the possibility for foreign participation in development or procurement. This, in turn, could help drive down costs even further.

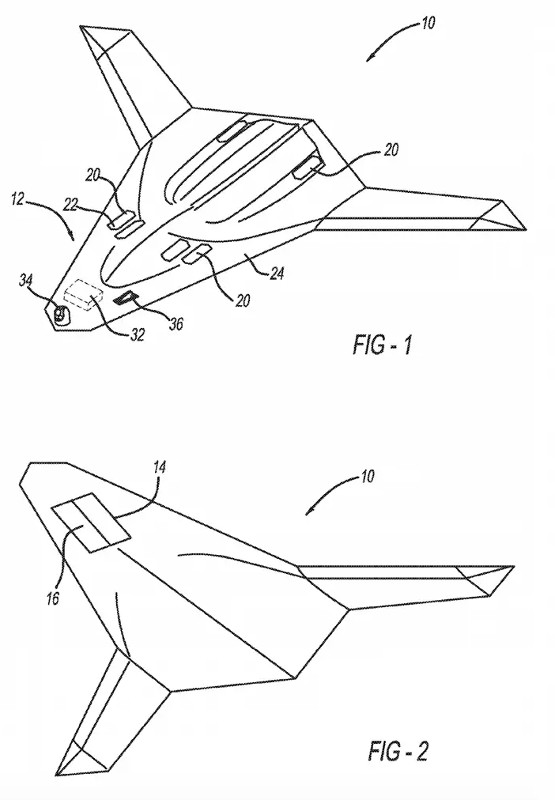

More interestingly, though, NAVAIR specifically mentions the possibility of adding this system to future unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) that would act as escorts for the U.S. military’s combat support aircraft. The Air Force has been particularly active publicly in this space, advancing the concept of a pilotless “loyal wingman” that can coordinate semi-autonomous operations with aircraft. The U.S. Marines Corps has conducted similar experiments, as well. The main focus of those efforts has been teaming the drones with combat jets rather than with larger combat support platforms.

But providing an aerial perimeter defense against those platforms would make a lot of sense. America’s potential opponents have long been growing more aware that they might be able to significantly hamper U.S. military operations by focusing kinetic and non-kinetic attacks

on the tankers, command and control, and other aircraft supporting an increasingly large fleet of low-observable aircraft. Using unmanned aircraft in this role would free up manned platforms, or more advanced UCAVs, from having to provide this localized defense, as well.

Of course, the Navy’s HKSPCS concept is hardly the first time the U.S. military and private contractors have investigated adding self-protection systems using small, kinetic interceptors to aircraft. In 2015, Lockheed Martin revealed it was working on a similar defensive suite for the Air Force as part of that service’s Miniature Self-Defense Munition (MSDM) program. The next year, Raytheon received a $14 million contract for various missile development, including additional work on the MSDM system.

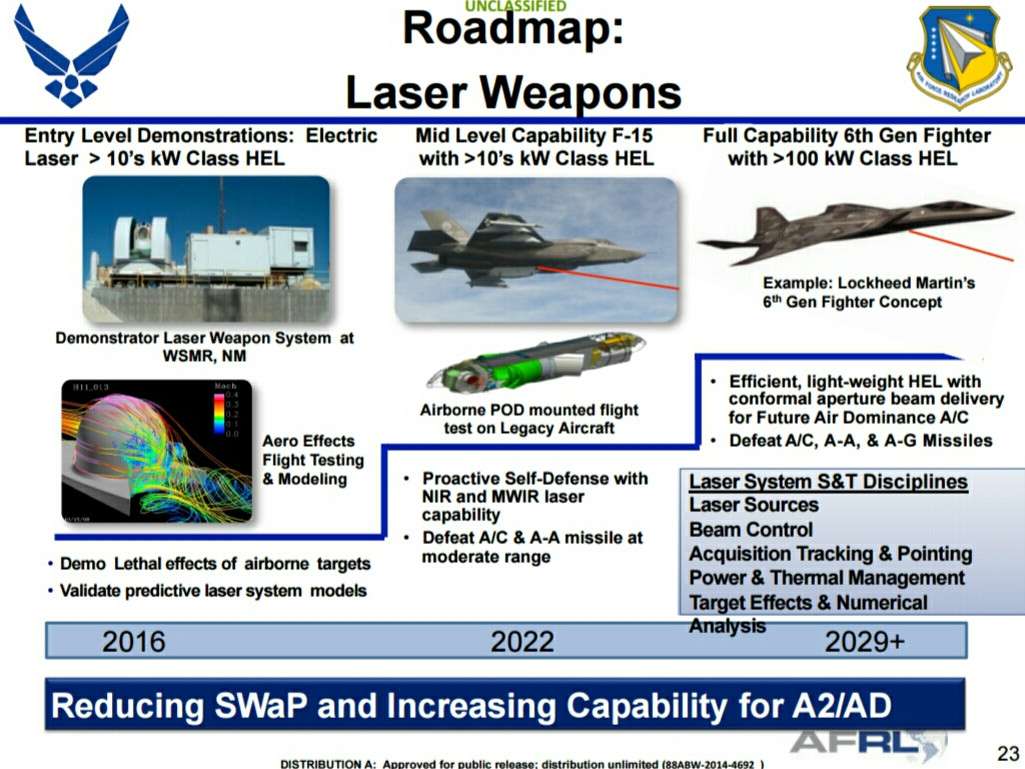

It’s unclear whether or not this system is still in development. The Air Force has publicly shifted attention to a laser-based hard-kill system called the Self-protect High Energy Laser Demonstrator (SHiELD). This program has focused mainly on getting that system onto fighter jet-sized aircraft, but the service has since said it is looking into adding it to larger aircraft, such as tankers, as well.

And, as already noted, Northrop Grumman’s patent shows almost exactly the kind of system NAVAIR seems to be describing. The associated imagery showed the system on what appeared to be a stealthy UCAV, but the description said it could be suitable for any type of aircraft, including helicopters.

The Navy itself is working on a separate hard-kill active protection system to defend rotary-wing aircraft from rocket-propelled grenades. This program, called the Helicopter Active RPG Protection (HARP), is the only hard-kill self-protection system for aircraft that the Navy included in research and development portion of its budget request for the 2019 fiscal year. In 2012, Israeli firm Rafael demonstrated a prototype of an air-launched interceptor that could shoot down RPGs.

A hard-kill system for larger aircraft might also be able to tackle these less advanced threats and would definitely be an added boon in guarding against the increasing danger of short-range, man-portable surface to air missiles. These shoulder-fired systems continue to proliferate around the world and terrorist and insurgents continue to make good use of them to bring down low- and slow-flying aircraft and drones.

The biggest limitation of all of these hard-kill systems using physical interceptors is their magazine depth, which effectively turns them into dead weight when they run out of ammunition. Laser-based systems could offer significantly more total engagements, but each projector can only shoot at a single target at a time and needs to keep its beam on the target for an extended period of time. Clouds, smoke, and other obscurants can easily impact the range and power of the beam and only one of the turreted lasers can’t provide full 360 coverage around an aircraft by itself.

NAVAIR’s HKSPCS may indicate the Navy, as well as other services, are looking for additional alternatives as a hedge against one type of weapon, such as a laser, being able to offer total protective suite by itself. A hard kill system would also likely work best as part of a layered defensive approach “adjunct” to existing and other future defensive suites, rather than a straight alternative to them, providing a last line of defense against an incoming missile.

As noted, the final launcher design might be able to fire decoys or other types of projectiles to expand its capabilities, too. The various systems might be able to share a common set of sensors to detect and target incoming threats, as well.

Combining the hard-kill system and other defenses with a picket of unmanned platforms might be able to mitigate these limitations. An individual UCAV might only need to carry one or two types of protective systems, reducing its overall size and cost. It could then work in concert with other drones in a small group to provide the most effective anti-missile bubble possible around one or more manned aircraft.

Whatever the Navy ultimately envisions for its hard-kill self-defense arrangement working, the aircraft the service is interested in protecting are increasingly vulnerable now to potential adversaries such as Russia and China, which have made significant investments in advanced aircraft and improved, networked air defenses. While HKSPCS might not offer a complete defense for larger transport and combat support platforms by itself, it would definitely be an important part of a multi-part defensive suite for those vital aircraft.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com