A bipartisan bill introduced by Senators Lankford (R-OK), Tillis (R-NC), and Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) would prevent the transfer of F-35s to Turkey and keep the country from establishing a maintenance depot for the stealth fighters. Turkey has been one of six prime F-35 partner nations since 2002 and one of its biggest customers, with 116 of the stealth fighters on order.

Under this legislation, the White House would to certify that Ankara isn’t working to degrade NATO interoperability, exposing NATO assets to hostile actors, degrading the security of NATO member countries, seeking to import weapons from a foreign country under sanction by the U.S., and wrongfully or unlawfully detaining any American citizens.

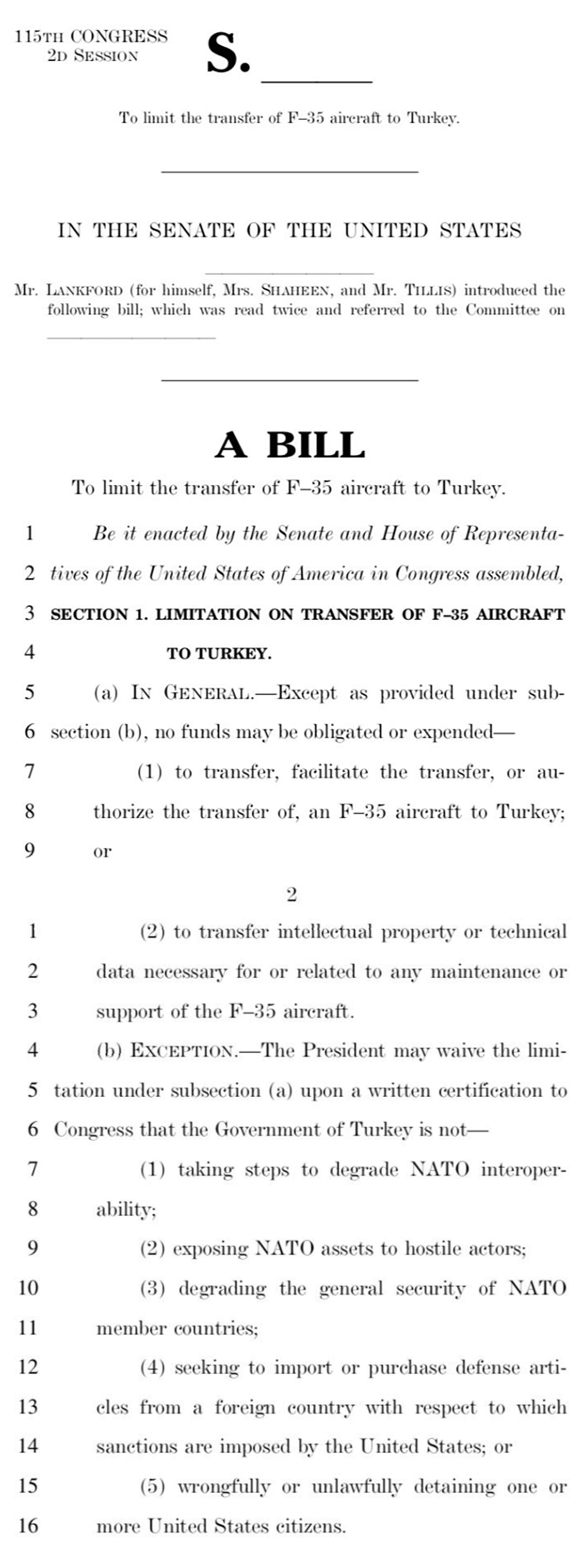

The bill reads:

Senator Lankford said the following in an official statement regarding the reasoning behind the bill:

“Senators Shaheen and Tillis have worked diligently with me and others in Congress to address America’s rapidly deteriorating relationship with Turkey… I applaud our State Department for their ceaseless work to improve the US-Turkey relationship, but President Erdogan has continued down a path of reckless governance and disregard for the rule of law. Individual freedoms have been increasingly diminished as Erdogan consolidates power for himself, and Turkey’s strategic decisions regrettably fall more and more out of line with, and at times in contrast to, US interests.

These factors make the transfer of sensitive F-35 technology and cutting-edge capabilities to Erdogan’s regime increasingly risky. Furthermore, the Turkish government continues to move closer and closer to Russia, as they hold an innocent American pastor, Andrew Brunson, in prison to use him as a pawn in political negotiations. The United States does not reward hostage-taking of American citizens; such action instead will be met with the kind of punitive measures this bill would enact.”

Though not specifically stated, the first four points deal almost entirely with Turkey’s planned purchase of S-400 surface-to-air missile systems. Since 2015, the Turkish military has been looking to purchase a new, long-range SAM to replace a number of aging Cold War-era systems it still has in service. That year, a previous plan to buy Chinese FD-2000s collapsed amid pressure from the United States and other NATO members for many of the reasons Lankford and Shaheen cite in their proposed legislation. You can read more about that saga in detail here.

But in 2017, Turkey announced it had signed a contract with Russia to buy the S-400s, with an eye toward some level of domestic industrial cooperation or co-production, which had always been a major secondary goal for the deal. As they had when Turkish authorities said they were going to buy the Chinese weapons, the United States and other NATO members expressed their dismay over the plan, saying that the Russian systems wouldn’t work with the alliances networks and other constructs and that they could risk exposing sensitive information to the Kremlin. Concerns about the potential of Moscow gaining information about the F-35 and how the S-400 performs against it have only grown since then, especially after Turkey stated that it would seek to fully integrate the F-35 with the rest of its own military networks.

Unlike in 2015, though, Turkey, and in particular its President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, have been defiant and insisted that the S-400 deal will go ahead no matter what. The Turkish president has specifically stated that there is a double standard at play since Greece already owns and operates older Russian S-300PMU surface-to-air missile systems. However, Greece is not part of the F-35 program and only ended up with those weapons as part of a deal to allay Turkish concerns about Cyprus’ military capabilities. Cyprus, which is not a NATO member, has been in the middle of a conflict between Greece and Turkey since 1974, when ethnic Greek Cypriots staged a coup, prompting Turkey to invade ostensibly to protect the island’s ethnic Turkish minority, leaving it partially divided to this day.

When Cyprus purchased the S-300s in 1997, Turkey threatened a military strike to destroy them. The Greek government then stepped in and took them in a swap for other air defense systems that Turkey saw as less threatening to its interests. It’s true that Greece has been looking to either upgrade these systems or potentially purchase newer versions, such as the S-400, from Russia for more than a decade, but there has been no real movement in that regard as of yet.

Otherwise, Turkey’s relations with the United States had already been strained following a coup attempt in 2016. Erdoğan blamed former political ally and Muslim cleric Fethullah Gülen of masterminding the plot, though he has yet to provide any firm evidence of this. Gülen, who lives in self-imposed exile in the United States, is an outspoken critic of the Turkish leader’s increasingly authoritarian tendencies. The United States has refused to extradite him to stand trial in Turkey until the government there provides substantive evidence to support its claims.

In response, Erdoğan has sought to increase ties America’s traditional opponents in the region, including Russia and Iran, and has openly threatened American troops in neighboring Syria over their support for Kurdish groups that the Turkish government sees as terrorists. The Turkish president himself has accused the U.S. military of running a “terror Army” and has launched unilateral intervention into northwestern Syria in January 2018 against the expressed wishes of the U.S. government.

The United States, in turn, says Turkey’s actions have drawn attention away from fighting ISIS terrorists at a critical moment, which appears to have given the group space to regroup. This could also be seen as a reason for Lankford and Shaheen to suggest Turkish authorities may be “degrading the general security of NATO member countries,” many of whom have seen ISIS sympathizers return from fighting in Iraq and Syria or have suffered outright ISIS-inspired terror attacks on their soil.

The last point has to do with Turkey’s arrest of Andrew Brunson, an American evangelical Presbyterian minister, who has lived and worked in Turkey for more than two decades, on charges of espionage and attempting to overthrow the government. Turkish officials detained him as part of a massive crackdown following the 2016 coup attempt that saw thousands of Turkish citizens expelled from public service. Many of those individuals subsequent faced arrest for various charges. Not surprisingly, Erdoğan has offered to exchange Brunson for Gülen.

With all this in mind, there have been repeated calls for stopping the export of the F-35 to Turkey and for the U.S. to pull its tactical nuclear weapons out of Incirlik Air Base in Turkey, but this is the first time those calls have morphed into legislation. It will be interesting to see how the Trump administration, which has retained relatively close ties with Erdogan since coming into office, and Turkey itself reacts to the bill. But considering Turkey has already spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the F-35 program, has billions in industrial offsets tied up in the deal, and has been molding its future air power strategy around it, it’s safe to say that the move will make some serious diplomatic waves.

Maybe the biggest take away from this development is that it is yet another signal that the long-held relationship, even on a military level, between the U.S. and Turkey is eroding at an increasing rate. What that means for the NATO alliance and the region as a whole is still yet to be fully understood.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com