As the U.S. Navy considers retiring one or both of its purpose-built hospital ships, it has established a formal team to examine whether a larger number of smaller ships could provide a viable alternative in at least some situations. A number of proposals already exist, including a conversion or purpose-built medical derivative of the San Antonio-class amphibious ship, a similar variant of Spearhead-class Expeditionary Fast Transport, and a modular hospital package for the service’s new giant Expeditionary Sea Bases.

U.S. Navy Vice Admiral William Merz publicly disclosed the existence of the so-called Requirement Evaluation Team, or RET, at a hearing before the House Armed Services Committee Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee on April 13, 2018. It first emerged the month before that at least one of the service’s two dedicated hospital ships – USNS Mercy and USNS Comfort – could end up in mothballs by the end of 2019, which quickly drew the ire of lawmakers who cited those ships’ value for both combat and humanitarian missions.

“The problem with those [hospital] ships is, there’s only two of them, and they’re big, and we’re moving to a more distributed maritime operations construct,” Merz explained at the April 2018 hearing. “There’s no lack of commitment [to this medical capability]; matter of fact, we’re taking a broader look at the capabilities on whether or not they are aligned with the way we plan to fight our future battles. So you’re going to see that requirement surface probably this year, and then we’ll start the process on how we’re going to fill that requirement.”

Although the Navy is still crafting these requirements for a future afloat medical force, the ship-building industry appears to have already gotten the message that there could be demand for new and novel hospital ship concepts. So far, the potential designs are all based on existing hullforms.

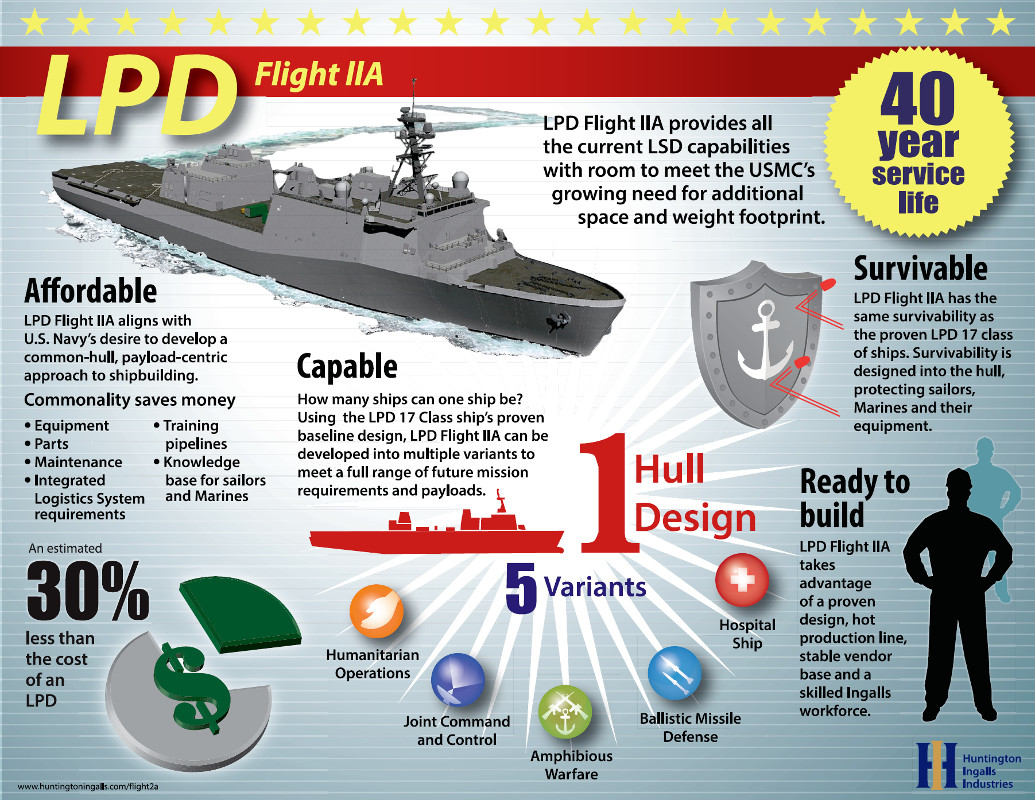

Huntington Ingalls has suggested its future Flight II San Antonio-class landing platform docks, or derivatives using a single hull shape, could fill the hospital ship role. At present, the Navy is already planning to buy more than a dozen of these ships, which it had previously referred to as LX(R), and could potentially decide to convert one or more to a hospital ship configuration.

The Newport News-based shipbuilder had also proposed the amphibious ships as the potential basis for new command and control vessels, ballistic missile defense platforms with interceptors and additional radars, and a purpose-built humanitarian relief type – a multi-mission concept it calls Flight IIA. This would be possible thanks to the use of standardized mission spaces within the common hull, but the different types would not be rapidly reconfigurable after construction.

With the added benefit of a well deck, a San Antonio-derived hospital ship might offer new capabilities over the Mercy and Comfort, able to get patients on board via helicopters or V-22 Osprey tilt-rotors, landing craft, or other small boats. This could both potentially speed up how fast personnel get to medical care, as well as offering more flexibility in how to get them to the ship at all in what could be a life-or-death situation.

This commonality, combined with an in-production design, could make it a cost-effective proposition to buy additional San Antonio-based hospital variants on top of the existing buy, as well. Huntington Ingalls claims that based on its existing experience, plus the Navy’s established training and logistics pipelines, will make its updated version significantly cheaper to build and operate than the original examples.

This cost factor could be an important consideration since a San Antonio-based ship may not be able to truly offer a one-for-one replacement for either Mercy or Comfort. The current versions of the landing platform dock are more than 200 feet shorter and a displacement of 25,300 tons – around a third of that of the dedicated hospital ships.

In turn, it’s not clear whether it would be able to house a full Role 3 medical facility, as is the case with Mercy and Comfort. Based on the U.S. military’s definition, this level of capability includes multiple capable operating theaters, additional diagnostic facilities, and more specialized intensive care facilities, along with other on-board resources such as a blood bank and oxygen generation plant.

There’s just a matter of overall volume, as well. Mercy and Comfort can accommodate up to 1,000 patients at a time, a floating medical capacity that simply does not exist in any other navy in the world. That being said, the existing San Antonios do already have space to accommodate an amphibious force of more than 700 individuals, along with garage and storage space for vehicles and other equipment, on top of their crew of more than 300 personnel.

If it does have more limited capabilities, a San Antonio hospital ship might only be able to act as a more intermediary care center, with the Navy then having to develop operating concepts to rapidly move seriously injured patients on to more robust facilities. This could be a difficult proposition, especially during the kind of distributed operations Vice Admiral Merz mentioned as being increasingly important.

These same issues apply to transforming the USS Lewis B. Puller, or either of her two future sister Expeditionary Sea Bases, into a floating hospital using modular medical packages. With the Navy only planning to acquire three of those highly specialized ships at present, it also difficult to imagine the service wanting to limit their capabilities by assigning them a single role. We at The War Zone previously examined this particular proposal in greater depth, which you can find here.

Regardless, in any potential crisis in the Western Pacific, for example, the “tyranny of distance” could quickly place American forces hundreds, if not thousands of miles from more established medical care. It simply might not be practical to have hospital ships without a Role 3 capability, even if it might be possible to operate more of them for the same cost as Mercy or Comfort.

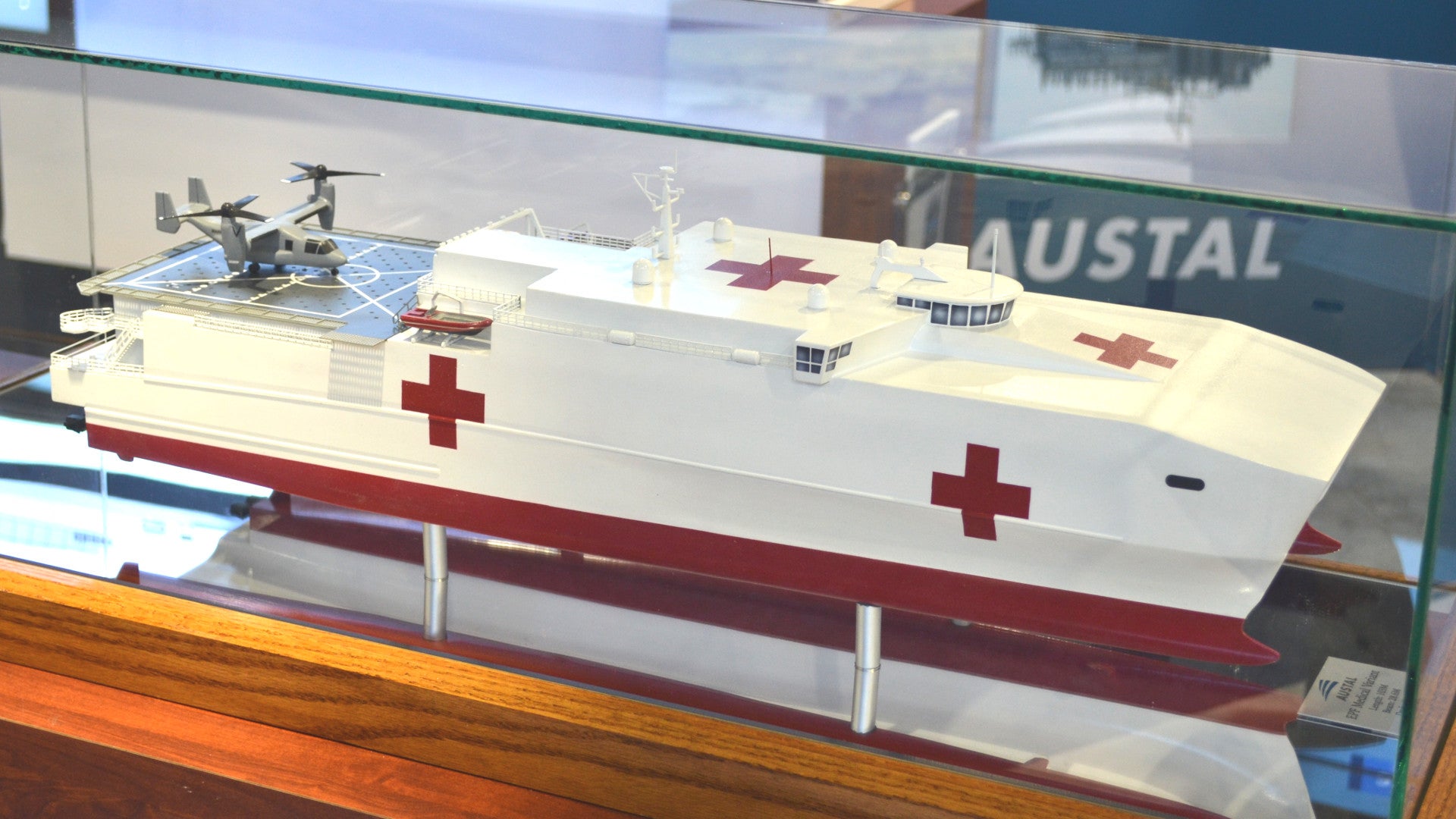

And there is where a separate proposal from Austal USA might come into play. The Alabama-based subsidiary of Australian firm Austal has pitched an even smaller, more potentially distributed idea using the Spearhead-class Expeditionary Fast Transport, also known by the abbreviation EPF. Previously known as the Joint High Speed Vessel, or JHSV, the Navy eventually expects to have a fleet of 12 of these catamaran ships, which can reach a top speed of 50 miles per hour.

The EPF would be even less able to carry a Role 3 medical facility, but might be able to act as a fast-moving link between a combat zone or other crisis area and larger afloat or land-based medical facilities. The Navy has already been using these ships as a means of quickly repositioning ground forces in the Pacific and is exploring other potential uses for the vessels, including as small, distributed platforms loaded with mine-hunting capabilities, unmanned aerial vehicles or tethered aerostats, or even stand-off weapons, such as electromagnetic railguns.

Both Huntington Ingalls and Austal USA also note that their ships have flight decks that will be able to accommodate the V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor, which could further extend their ability to rapidly accept, stabilize, and move patients onward for further treatment. As it stands now, the landing pads on Mercy and Comfort do not have the heat treating necessary to withstand the blast from that aircraft’s turboprop engines during a vertical take-off or landing.

One of the Navy’s future missions could be an “a distributed hospital capability, and these are going to be fairly challenging requirements,” Vice Admiral Merz said at the April 2018 hearing. “It’s going to have to be able to support a V-22, for instance, so how do you manage the size of that and the speed and how it’s going to go.”

Having some mix of less intensive medical ships that are cheaper to operate might also free up ships like Mercy and Comfort, or any future replacements, for more demanding missions, as well. A major criticism of the larger hospital ships is that it takes a significant amount of time and resources to activate them for any mission then the vessels often incur exorbitant costs just to perform limited humanitarian port visits where the crew might not even see 100 patients. While these sorts of “soft power,” non-combat missions are invaluable for advancing American interests abroad, it’s reasonable to ask whether this is an appropriate use of unique and specialized capabilities.

At the same time, though, it’s not clear how using San Antonios or Spearheads would necessarily provide more operational flexibility or present a cost-effective alternative to a more purpose-built design akin to the existing Mercy or Comfort. The planned purchases of the landing platform docks and expeditionary fast transports are based on long-standing, established requirements. Putting them even semi-permanently into a dedicated medical role would prevent them from performing those other tasks.

Purchasing additional ships of either class, no matter the potential cost savings, could be just as expensive a proposition as extending the life of the existing hospital ships or purchasing new ones. Even with a 30 percent reduction in unit price, the San Antonio FLight IIs would still be more than $1.4 billion apiece. The Spearheads are around $180 million each.

The Navy only asked for $120 million in its most recent budget request for the 2019 fiscal year to sustain the Mercy and the Comfort, and has proposed putting Mercy in a reserve status with a skeleton crew for half the year that will trim $23 million from the typical annual operating costs. The service could increase that budget by a factor of 10 and it would still be cheaper than buying just one potentially less capable San Antonio-based hospital ship.

However the Navy decides to proceed, it will have to do so relatively soon. Comfort is increasingly in desperate need of a major overhaul, which could sideline the ship for months and is among the factors that prompted the service to consider putting her into a reserve status or retiring her outright. Mercy is in better condition, but having just one of these ships would inherently limit the Navy’s ability to rapidly provide this capability or do so in multiple theaters at once.

“[Comfort’s] replacement’s not ready, so we are evaluating what it would take to do a life extension on her,” Merz told legislators in April 2018. “Her sister ship is in good shape, she’ll be around for quite a while, and there may be other opportunities to fill in the sea-based medical support that we need to provide. So we’re casting a wide net on how to meet that specific capability.”

All told, it seems increasingly clear that the Navy is interested in a more varied set of afloat medical capabilities. It remains to be seen whether a combination of smaller, less capable ships will truly be able to fill the gap leftover if the service does retire one or both of its specialized hospital ships.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com