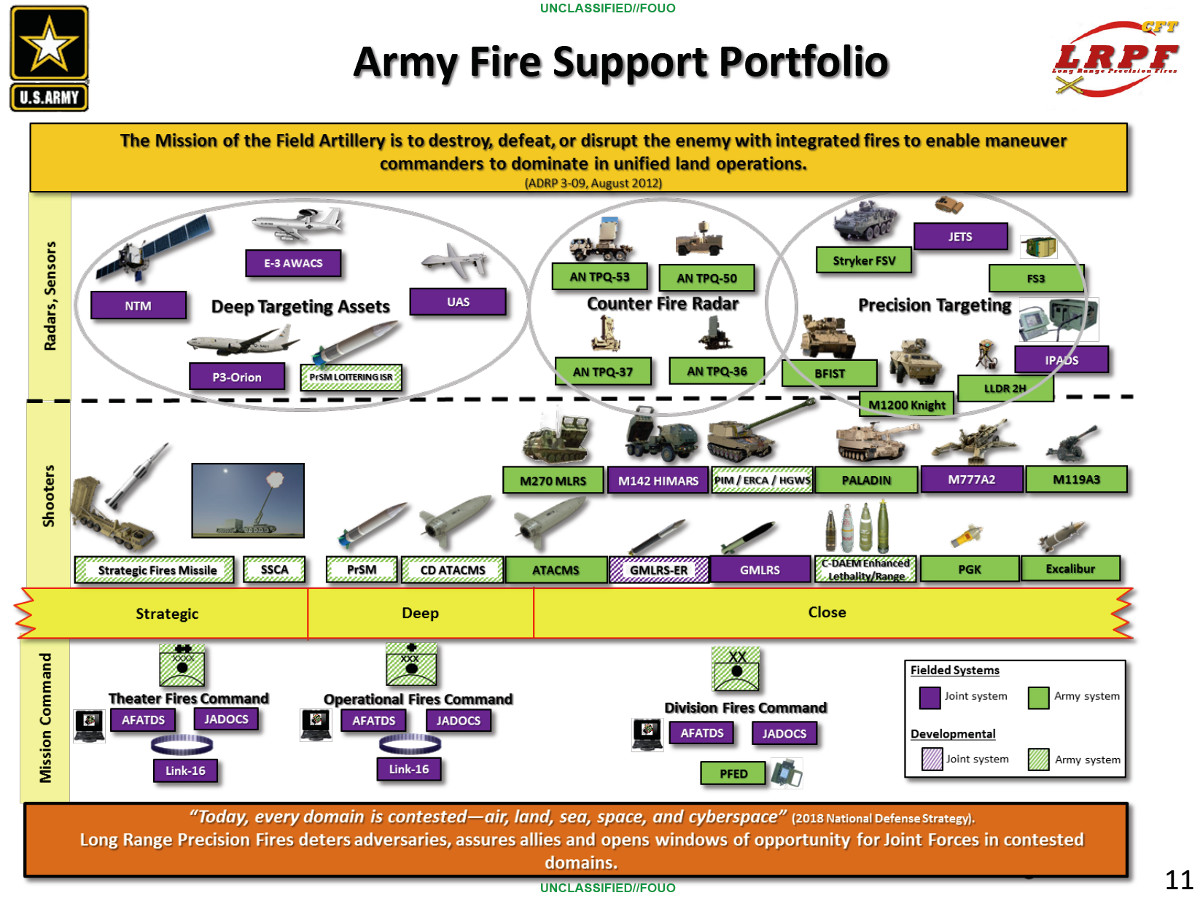

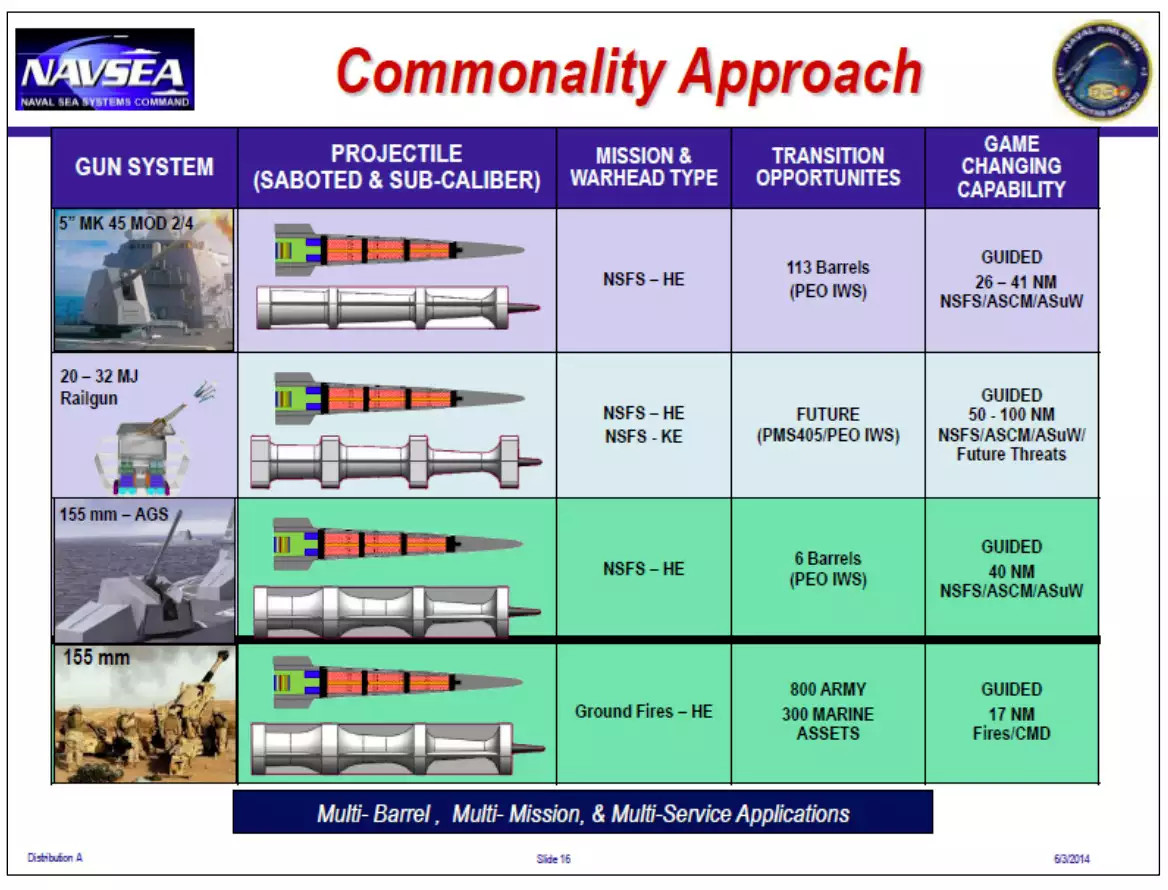

The U.S. Army is looking to develop a slew of new extended range artillery weapons to counter what it views as a growing imbalance in this regard with potential opponents, especially Russia. These new proposals include the addition of a hypervelocity or ramjet-powered projectile for existing cannons, a new quasi-ballistic missile with anti-tank and loitering munition payloads, an ultra long range “supergun,” and a potentially treaty-busting medium-range missile.

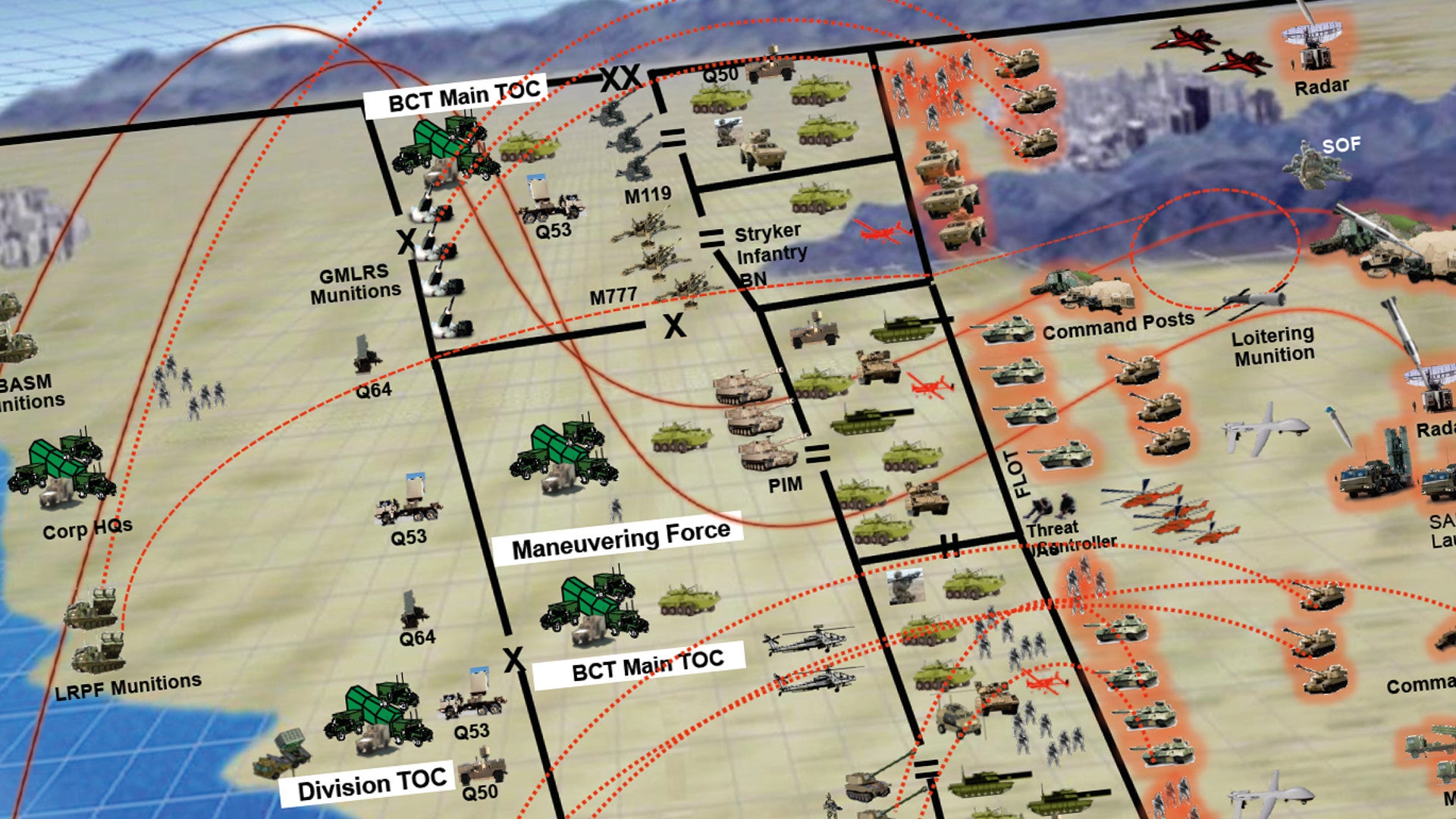

Representatives from the service’s new so-called “cross functional team,” or CFT, for Long Range Precision Fires, or LRPF, described this potential mix of systems at the Association of the United States Army’s Global Force Symposium in March 2018.

In 2017, the Army announced plans to create eight CFTs within a new Futures Command, bringing together service members and subject matter experts to explore new technologies in a variety of different functional areas. In addition to LRPF, these include groups focused on developments relating to the Next Generation Combat Vehicle; Future Vertical Lift; Network Command, Control, Communication, and Intelligence; Assured Positioning, Navigation, and Timing; Air and Missile Defense; Soldier Lethality; and the Synthetic Training Environment.

“We’ve got to push the maximum range of all systems under development for close, deep and strategic, and we have got to outgun the enemy,” U.S. Army General Robert Brown, head of U.S. Army Pacific Command, said during a panel discussion at the Global Force Symposium. “We don’t do that right now; it’s a huge gap. … We need cannons that fire as far as rockets today. We need rockets that fire as far as today’s missiles, and we need missiles out to 499 kilometers.”

At the same talk, U.S. Army Brigadier General Stephen Maranian, head of the LRPF CFT, outlined how the service might be able to go about meeting that demand. Many of the systems he described initially are already in development to one degree or another.

Extended-range howitzers

The Army is already testing the XM1113 rocket-assisted, high-explosive 155mm shell. This will extend the maximum range of the service’s M777 towed howitzers and M109A6 and A7 self-propelled types from approximately 19 miles with existing rocket-boosted ammunition to some 25 miles.

Maranian said that the new shells would begin reaching operational units in two and half years, though it’s not entirely clear why it will take so long. As noted, shorter range rocket-assisted projectiles are in service and this one has been in development for some time already. In addition, the latest M777 and M109 howitzers can already hit targets at 25 miles with the M982 Excalibur GPS-guided shell.

There is also work underway to add a longer barrel cannon and more robust breech mechanism to the M777s and M109s in order to further push their maximum range all the way out to 43 miles. An auto-loader capability on either weapon could also further improve their capabilities, especially when coupled with a computer-assisted targeting system.

This would allow artillery crews to rapidly fire a number of shells from a single weapon at a variety of points close together, with the rounds all falling in rapid succession, to saturate an enemy unit while giving them little time to react or seek cover. Many of these features were present on the Army’s abortive XM2001 Crusader self-propelled 155mm howitzer, which the service cancelled in 2002.

These upgrades would put the weapons on par with Russia’s autoloader-equipped 152mm self-propelled 2S35 Koalitsiya-SV, which also has a range of approximately 43 miles. This weapon, which has been in some level of service since 2016, is one of many the Army is concerned about outranging their existing systems, which could allow them escape immediate counter battery fire during a potential conflict in Europe.

The Army isn’t content to be on par with potential hostile forces, though. The goal is always to have a definitive “overmatch” in capabilities that gives American troops the edge.

Railguns and ramjets

So when it comes to cannon artillery in maneuver bridges, the service is hoping that rocket assisted rounds and longer barrel cannons will only be a prelude to more game-changing weapons. This Extended Range Cannon Artillery Program, or ECRA, is presently considering one of two options, either a hypervelocity projectile or a gun-launched, air-breathing ramjet-powered, quasi-missile.

The Army is already experimenting with electro-magnetic railguns that can fire projectiles at hypersonic speeds, above Mach 6, and extremely aerodynamic projectiles that its conventional howitzers could be able lob at near hypersonic speeds. Units with a mobile, land-based rail gun might be able to effectively attack targets anywhere within an 80 to 100 mile radius – greater than that available with the Army’s existing 226mm guided artillery rockets – of their firing position and do so rapidly, accurately, and with little to no warning to the enemy.

The speed and precision of a railgun mean that could be able to take on an anti-aircraft or counter rockets, artillery, and mortar mission in addition to a conventional artillery role. And without relying on chemical propellant charges, it would be able to do this with greater magazine depth and less strain on the Army logistics chain.

A gun-launched ramjet-powered round could be capable of high supersonic speeds, as well, but might have the benefit of being able to independently maneuver after launch. This would allow for distributed attacks from numerous directions, which could confuse an enemy or otherwise disrupt their plans.

The Precision Strike Missile

In line with General Brown’s comments, with cannon artillery that can hit targets at the ranges of existing rockets, the Army is looking to push the range of those weapons to land-attack cruise and short-range ballistic missile ranges. There is an effort underway to extend the range of standard 226mm GPS-guided artillery rockets to approximately 75 miles.

However, the big push is development program for what is now called as the Precision Strike Missile, or PrSM. Also known as DeepStrike, Raytheon is crafting this weapon as a replacement for the existing quasi-ballistic Army Tactical Missile System missile, or ATACMS.

The PrSM will be able to strike targets just over 310 miles away – a very specific range we’ll come back to later on – nearly 125 miles greater than that of ATACMS. It will also be more accurate and smaller.

This latter design decision means that two of the new missiles will be able to fit in the same space as a single one of the older types. As such, a truck-mounted High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) launcher will be able to carry two of the long-range weapons at once, while the tracked Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) will be able to fire four before needing to reload.

At present, the Army expects that a combination of manned battlefield surveillance and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft, drones, and space-based sensors will be able to provide the necessary targeting information for these weapons against both static and mobile targets. In the future, low-observable platforms, such as the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, will be able to further extend that sensor range into denied areas. Land-based radars and artillery spotters on foot and in vehicles would continue in their traditional roles for the short-range cannon artillery.

Additional capabilities

Beyond that, the service is interested in whether or not the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) itself, or a variant thereof, might be able to provide intelligence gathering capabilities, according to Brigadier General Maranian’s presentation. It’s not clear how this would exactly work, but it seems likely that the concept would involve a small drone payload in the missile. A weapon with a ballistic or quasi-ballistic trajectory does not otherwise lend itself to surveillance or reconnaissance duties.

A single missile carrying some sort of reconnaissance payload might be able to act as a spotter for other missiles in denied, though, feeding them target information based on a set of baseline parameters. The U.S. Air Force is also exploring the potential of this concept of operations with regards to air-launched cruise missiles.

A more robust sensor package could also just open up the possibility of adding a man-in-the-loop targeting capability that would allow for more precise adjustments during the weapon’s terminal phase, which can be especially useful for engaging moving targets. This provides additional time to abort an attack if it becomes apparent that innocent bystanders have entered the target area, as well, potentially reducing collateral damage.

The video below describes the features of the Israeli Spike anti-tank missile family, which have a man-in-the-loop targeting capability.

It might be able to turn the weapon into a loitering munition of sorts or the missile could carry smaller such systems that it could deploy over a target area. The Army says that by adding smart or loitering sub-munitions with some additional stand-off capability might be able extend the functional range of the weapon out an additional 125 miles or so.

This would make HIMARS and MLRS launchers more capable than Russian extended range rocket artillery and their acknowledged ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles, such as Iskander-M, Iskander-K, and Bastion-P, the latter being officially an anti-ship missile, but having demonstrated a secondary land-attack capability in Syria. Perhaps more importantly, it could allow PrSMs to strike long-range integrated air defense positions with surface-to-air missile systems such as the S-300 and S-400, which could limit the effectiveness of American or allied air power in the initial stages of a conflict.

“Because of the power and range and the lethality of these Russian air defenses, it’s going to make all forms of air support much more difficult, and the ground forces are going to feel the effects,” Dr. John Gordon, a senior policy researcher from the think tank RAND and another member of the AUSA panel in March 2018, said. “It’s certainly going to put a premium on U.S. Army field artillery.”

Getting to ‘strategic’ range

Air defenses, especially long-range radars and other sensor nodes that might even be able to spot low-observable aircraft in the future, are among the main drivers for the Army’s interest in new, weapons with what it calls “strategic range.” This would also be able to strike at base areas, hardened command centers, and other similar targets well behind the front lines in a high-end conflict.

The two systems in question, the Strategic Strike Artillery Cannon and the Strategic Fire Missile, are also the least defined as of yet. The underlying issue, however, seems clear.

Russia and the United States are party to a bilateral arms control agreement known as the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF. Despite its name, this deal prohibits either side from fielding conventional or nuclear-armed ground-launched cruise or ballistic missiles with maximum ranges anywhere from approximately 310 miles to 3,420 miles.

The agreement forced both sides to retire a number of different weapon systems. It’s also why the PrSM’s planned range tops out at around 310 miles, since otherwise the weapon would be in violation of the INF.

The United States has publicly accused the Russians of being in violation of the treaty with ground-launched cruise missile system called the 9M729 or SSC-8, which uses the same transporter-erector-launcher as the Iskander-M. he Kremlin in turn denies that this weapon even exists.

Using a loophole in the INF that allows for land-based missile research and development, the U.S. military has already begun studying the possibility of its own treaty-busting missile. The idea here is both to counter the capabilities of the SSC-8 and offer a potential bargaining chip to goad the Russians back into compliance with the agreement. We at The War Zone have already written in depth about the how such a negotiation might play out, which you can read here.

The Strategic Fires Missile, though, sounds exactly like the system reportedly under study. The Army says that it this weapon would have a range between 310 and 1,400 miles, will within the limits the INF prohibits.

At the Global Force Symposium in March 2018, Brigadier General Maranian suggested that this weapon would be INF-compliant, but it’s difficult to imagine how that could be the case. This would almost certainly require some creative legal interpretation of the deal.

Perhaps the Army might look into whether a missile with a 310 mile maximum range that launches a second “air-launched” missile skirts the accepted definitions. Using Army watercraft as the launch platform might allow the service to avoid the “land-based label.

Regardless of how it is configured, any such a weapon would be almost certainly to provoke complaints from Russian officials. In turn, it might make them feel vindicated in their decision to secretly abrogate the INF’s terms.

A ‘supergun’

And this is where the Strategic Strike Artillery Cannon would come into the picture. The INF does not cover such weapons, regardless of their range.

A cannon firing a chemically or electro-magnetically propelled round nearly 1,000 miles away could offer a way to strike targets well within denied areas, but in a way that is clearly compliant with the INF. The Army would actually have a surprisingly deep knowledge base to draw from in this regard, too. The service captured examples of the lesser known Nazi “vengeance weapons,” the V-3 long range gun, during World War II and extensive evaluated them afterwards.

Then, during the 1960s, the United States and Canada teamed up on the High Altitude Research Project, or HARP, which used modified 16-inch naval guns from fixed sites on land to explore the possibility of the system as a cost-effective means of launching objects into space. Though that weapon set an attitude record for a gun-launched projectile, it was only 110 miles.

It could serve as a good starting place for a larger “supergun,” though. The HARP gun’s designer, Gerald Bull, definitely thought so, shopping the idea of an ultra-long-range artillery weapon around the world after the project ended due to steadily improving rocket boosters and a loss of interest on the part of both the American and Canadian governments.

Infamously, Bull finally pitched an improved concept to Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein in the 1980s. The Babylon Gun’s design was supposed to offer a range of more than 450 miles, which would have put targets within Iran and Israel in strike distance.

The final weapon never came to fruition though. Assassins, alternately linked to Israel’s Mossad or Iran’s VEVAK, killed Bull in the Belgian capital Brussels in 1990. British customs also seized components for the weapon before they could reach Iraq and the project came to a complete halt after the United States-led intervention to liberate Kuwait and beat back Iraqi forces in 1991.

Bull’s concept for a multi-chamber artillery piece would still likely be one of the best chances for the Army to achieve the ranges it’s looking for with a gun system. The V-3 used a similar mechanism, with the Nazis referring to its multiple sections as a “high pressure pump” to cover its true function.

These types of designs work by propelling a shell with multiple explosive charges. Combined with a long barrel, this method gradually builds up pressure behind the projectile just like a rocket, which extends range and reduces wear and tear on the system at the same time.

Another option would be to pursue a larger railgun that might offer similar range. The conceptual design of the Army’s 32 mega joule electro-magnetic gun already requires two separate vehicles to carry the necessary power source and offers a maximum range of around 100 miles. A system with 10 times that range could have immense power requirements.

Strategic mobility

It’s questionable how mobile either a chemical supergun or a massive railgun might be at all, though. Historically, plans for super guns have called for them to be fixed in place, aimed broadly in the direction of a large target, such as a city, intended to cause terror and chaos rather that than more specific strategic effects. The World War I-era Paris Gun could traverse 360 degrees, but was still effectively immobile, as were the guns the Germans and the British used to shell each other across the English Channel during World War II.

The Strategic Strike Artillery Cannon might not need to move though. A fixed and properly hardened position could be able to hold a wide area at risk, which could deny an enemy freedom of movement through a large area.

This could be useful for trying to close of access to certain areas in a potential European conflict, especially in constrained multi-domain environments, such as the Baltic Sea or Black Sea. In those cases, various long range artillery weapons could work to neutralize anti-ship threats, as well as anti-aircraft ones, too.

By the strategic weapons, missiles or guns, might actually be better suited to the Pacific theater, where being able to deploy them with any rapidity to small island outposts could easily present a significant challenge to other potential opponents, such as China or North Korea. These weapons would have the range to engage targets in North Korea from distributed sites in South Korea and Japan or various Chinese outposts in the South China Sea from territory belonging to allied or partner nations, such as The Philippines or Vietnam. If they were capable of firing hypersonic projectiles, the weapons in those positions would be even more effective, able to take on time-sensitive targets or otherwise launch strikes with little advance warning.

This “an anti-access, area-denial capability all of our own to make potential adversaries think twice,” Brigadier General Maranian explained. They would “be deterred before making a decision of whether cost is worth the benefit of being provocative.”

A broader, joint-service approach

A Strategic Fires Missile with a mobile transport-erector-launcher could use the decks of amphibious ships as a firing platform, as well. In that regard, it’s very likely that the U.S. Marine Corps might be interested in a variety of the artillery systems the Army is proposing, including the PrSM, which would fit in that service’s HIMARS launchers, as well.

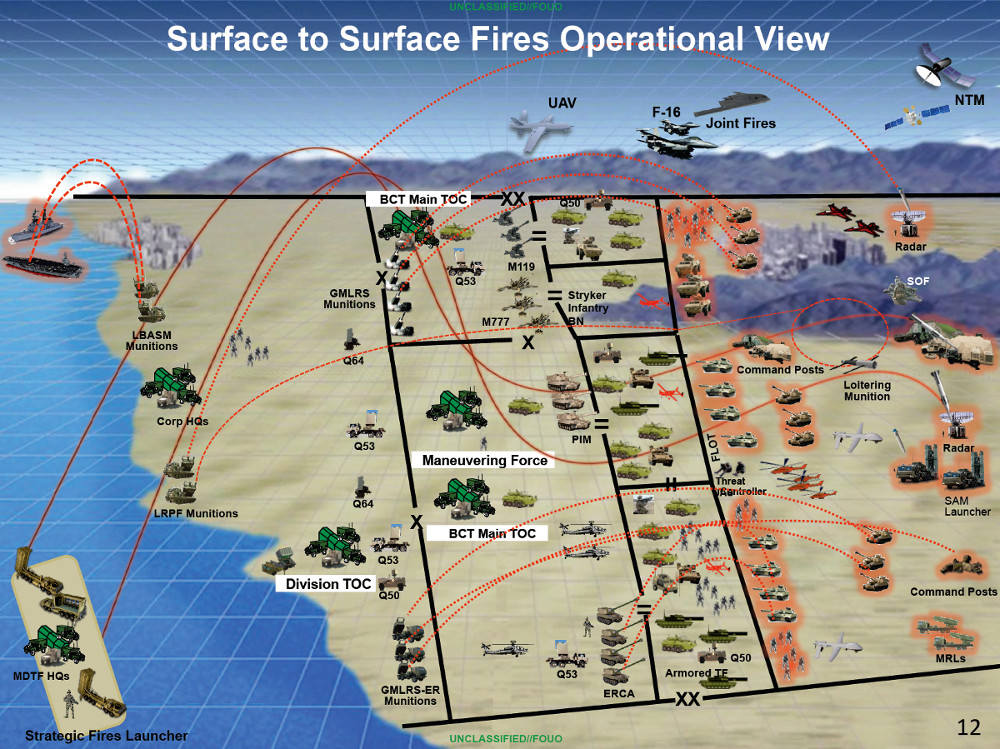

Interest from the Marines, or even from other services such as the U.S. Navy in related technologies such power sources for electro-magnetic guns, could help reduce the burdens on the Army both in terms of cost and other resources, too. This could be particularly important given the obviously ambitious concepts the service’s artillery-focused cross-functional team is considering and their apparent desire to make as many of them a reality as possible in as short a time frame as they can.

The Navy is itself looking to the Army and Marines for help with its own railgun program. That service is now pushing to field hypervelocity projectiles that will work with 155mm howitzers and five-inch naval guns, by only fly at speeds up to Mach 3, rather than Mach 6 or above.

The Army definitely doesn’t feel it has any time to lose in fielding new weapons. “The Russians take this stuff seriously; artillery has been the strong suit of the Russian Army since the days of the czars,” Gordon, the RAND researcher, who recently conducted a study on Russia’s capabilities for officials at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, the home of the Army’s main artillery school, said.

The service expects to begin testing the PrSM in 2019 and have the new, longer range conventional howitzers ready by 2023. With the aggressive schedule driven by existing, potential threats, Maranian’s cross functional team will have to begin fleshing out its concepts for the more advanced weapons soon.

Contact the author: jtrevithickpr@gmail.com