Lockheed has unveiled its MQ-25 Stingray carrier-based unmanned aerial tanker concept, and it’s impressive—but it’s still just a concept. No prototype exists of the aircraft, and that could be either a good thing or a bad thing depending on how the Navy actually evaluates the three proposed designs being offered before awarding a contract for four prototype aircraft late this Summer.

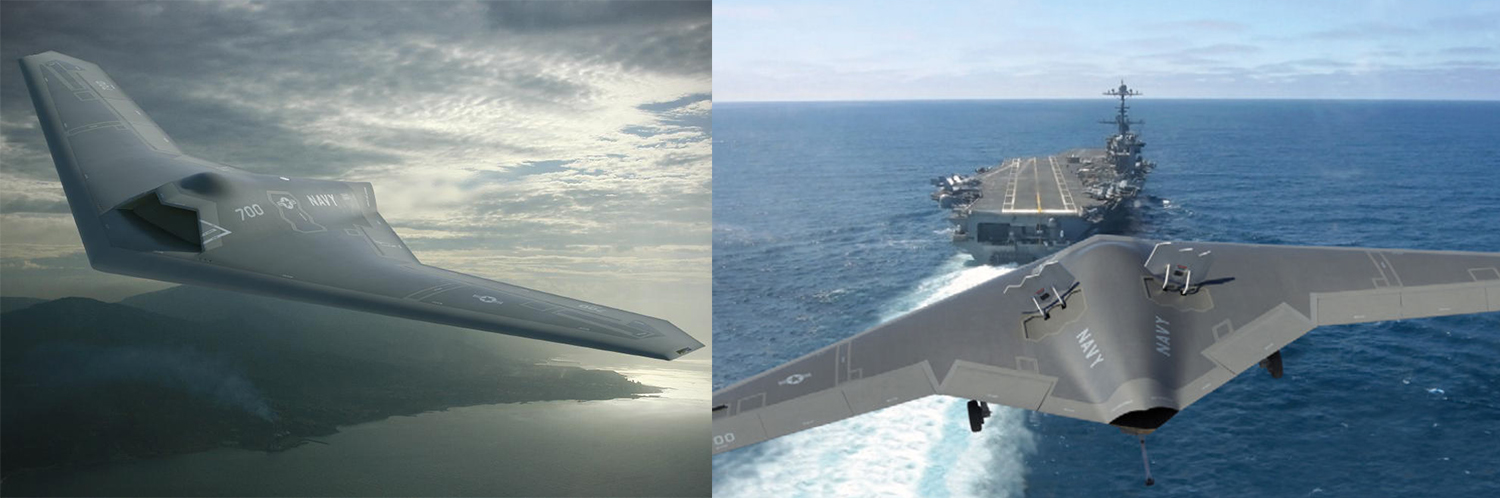

Our friend James Drew over at Aviation Week got the scoop, and has conveyed both concept art and some interesting details about the Skunk Works’ Stingray design. Like Boeing’s and General Atomics’ MQ-25 contenders, but to a lesser degree, Lockheed’s MQ-25 appears to be influenced by the company’s Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) concept that came before it.

That stealthy aircraft was dubbed the Sea Ghost and was a substantial outgrowth of the company’s proven RQ-170 Sentinel design, upscaled and refined for naval operations and the penetrating strike and reconnaissance mission. It’s possible, if not outright probable that a similar aircraft exists but in a non-navalized form in the classified world.

The Sea Ghost design was dropped after the Navy dumbed-down its carrier-based drone requirement to a tanker with limited surveillance capability—and one that didn’t have to penetrate into contested territory at all. As such, stealth requirements were jettisoned.

The company seems to have decided that a flying wing design with a dorsal inlet was still the best answer for the carrier-borne tanker requirement. This makes plenty of sense as a flying wing can hold and efficiently transport a lot of gas.

Drew writes that Skunk Works general manager Rob Weiss says that his team examined many different design concepts for the MQ-25 mission, but kept coming back to the flying-wing design for a number of reasons:

“Weiss says a flying-wing concept was always in the mix, and it kept coming out on top. A flying-wing aircraft has the benefit of being aerodynamically efficient and can carry more fuel for its size. Other benefits include a lower total parts count and reduced spot factor on the carrier deck with the wingtips folded up. Despite the flying-wing design being shorter in length, the landing gear and tail hook have enough separation to safely catch the arresting gear, rather than trip over it.”

Reducing the number of parts for an aircraft design is something the Skunk Works has been working tirelessly on for nearly two decades. The introduction of large-span composite structures and new kiln systems and manufacturing techniques has enhanced the feasibility of simplifying otherwise complex airframe designs dramatically. Experiments, both public (X-55), and at the time private (X-44, P-175), have resulted in a mastery of these processes and the use of it in production aircraft like the RQ-170.

The company actually locked its MQ-25 design less than a year ago, in mid-2017. So even though it borrows from prior Skunk Works work heavily, it is far closer to a clean-sheet design than a retooled variation of the Sea Ghost. And the differences between the two concepts are clearly evident.

Lockheed’s Stingray has a far less defined ‘w’ trailing edge, with an overall thick wing chord, and it’s more portly all around—a function of having to hold at least 14,000lbs of gas to pass along after flying 500 miles, while still retaining enough fuel to return to the carrier. In fact, the design’s trailing-edge is as close to a delta shape as it is to a stealthier swept saw-tooth one, giving it a resemblance to the abortive A-12 Avenger from three decades ago and a very notable Nazi aircraft design.

Instead of an angular and grated intake and a deeply buried engine like what’s found on the Sea Ghost, Lockheed’s MQ-25 has a simplified powerplant arrangement featuring a traditional elliptical intake with a relatively inline engine placement design. In other words, no ‘stealth’ in a place where it would matter most.

A conformal satellite communications enclosure, almost certainly in the Ku bad, sits atop the aircraft’s inlet, and a pair of UHF satellite communication antennas are seen attached to both sides of the MQ-25’s rear upper fuselage, between its rear engine fairing. Other antennas are bolted directly onto the aircraft’s fuselage as well. It’s not clear if the aircraft will feature its own probe for aerial refueling from other aircraft or not.

The aircraft will carry an electro-optical sensor turret for limited surveillance capabilities—a common feature for MQ-25 entrants—and a series of wide angle cameras in the aircraft’s nose will allow for control while operating on the carrier’s crowded deck. It’s not clear how much a human will have to do as part of this ground control concept or if hand gesture recognition is part of the system.

Drew reports that company has used a surrogate aircraft for testing the MQ-25’s deck handling system. As we previously reported, our sources state that the now unmasked X-44A demonstrator’s last test mission was to validate the MQ-25’s remote deck movement control concept.

What we don’t know is what command and control architecture the aircraft will operate on while on a mission, but it’s safe to assume it would be semi-autonomous in nature. In fact total autonomy for basic mission sequences seems likely as well, with the aircraft only calling home if there is an issue. Although somewhat shrouded in secrecy, Lockheed has made incredible strides in this area in recent years, including the development of synergistic cross-platform unmanned vehicle command and control interfaces.

The aircraft’s ventral area is dominated by two side-by-side hard-points. One carries the Cobham refueling pod that is a mandated hardware requirement by the Navy. The other could potentially carry a podded surface search radar, but other radar pods, modular communications relay systems, or even an electronic surveillance or warfare pod could be added in the future as well. An auxiliary fuel tank is also possible. An exposed tailhook sits behind the hard-points below the MQ-25’s engine.

It’s landing gear are clearly from the F-35C, which is no surprise as the Skunk Works’ has a long tradition of ‘borrowing’ existing components to lower-cost, shorten development time and alleviate risk.

The F-35C is also worth mentioning as it has given Lockheed a load of recent experience when it comes to fielding a modern fixed-wing naval tactical aircraft. In addition, some of the F-35’s sub-systems and architecture could not only benefit the MQ-25’s feasibility, effectiveness, and its cost but also help simplify logistics and maintenance aboard the ship.

While Boeing has a current and long-running pedigree with carrier-based aviation, General Atomics, which is putting a distant cousin of its Sea Avenger concept up for the MQ-25 prize doesn’t. The company does have more raw experience in the unmanned space than any contender. With this in mind, General Atomics has added Boeing to its team, which would work with its prior competitor should the company win the competition.

What Lockheed has that its competitors don’t is the Skunk Works, which intends to support this program throughout its entire life cycle if the Navy awards Lockheed the contract. That means more than just a cool name and legendary track record. The ‘bleeding-edge’ business unit has specialized in developing, maintaining, and evolving small fleets of high-tech military aircraft for over 75 years.

Considering the Navy intends to build just 72 MQ-25 production units, the MQ-25 enterprise could greatly benefit from the Skunk Works’ unique knowledge base of running similarly sized programs (U-2, SR-71, F-117, RQ-170) in the past. And clearly, adapting the MQ-25 airframe and packing on conformal radar arrays and electronic intelligence gathering equipment in exchange for some gas could be a relatively easy and logical development for the type and it could even lead to additional sales.

Overall it seems that Lockheed has not only put forward a very intriguing concept but has worked to make it as affordable as possible, and has fully embraced the fact that this is a flying truck with no low-observable ambitions. In doing so the company has gone a long way to separate itself from the competition and especially from Boeing, whose MQ-25 prototype is a reworked UCLASS concept built in 2014, years before the tanking mission became the central focus of the Navy’s carrier-based unmanned aircraft ambitions.

But at least Boeing actually has a prototype.

While this all sounds great from Lockheed, their’s is a paper machine. As for trusting their ability to produce this aircraft on time and on budget with the capabilities stated, the company can point to work dating back the X-44A and onto RQ-170 when it comes to flying-wing experience and to their recent work with the F-35C for carrier-based tactical aircraft know-how. At the same time they will have a tougher time doing so for work that could be closely related in the classified realm.

Supposedly General Atomics is rolling out their MQ-25 entrant within a matter of weeks, but even without it, they have been flying the Predator-C/Avenger, from which their design is supposedly based, for years. If, like Boeing, General Atomics does roll out an actual prototype, that could put Lockheed at a double disadvantage.

There is no requirement to create a flying demo aircraft for this competition, but the first pre-production prototypes will need to be delivered by 2021. Lockheed clearly decided on the lowest risk, highest reward approach by not moving to construct one. It also allowed them to easily put forward a largely fresh, tailor-made design, which is attractive. But will their word, what looks like a great design, and a solid pitch, be enough to win over the Navy who has historically assumed far less risk when it comes to aircraft procurement than its USAF counterpart? I guess we’ll have to wait about six months to find out.

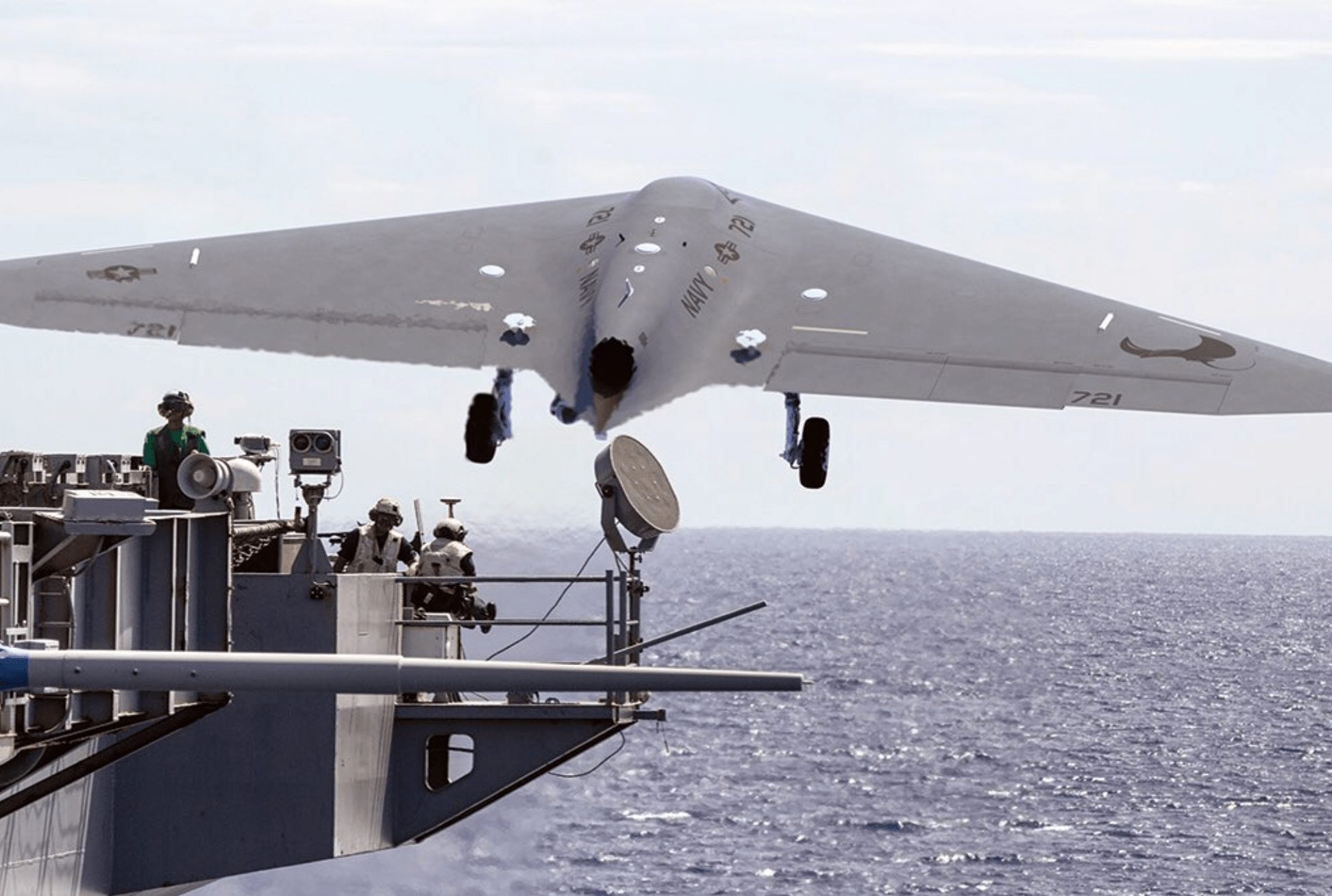

At the same time it’s worth reflecting on Northrop Grumman’s decision to pull out of the contest. They had by far the most mature design in the X-47B. It had already spent hundreds of hours in flight testing and had even operated from a carrier on multiple occasions, not to mention refueling itself from a tanker. Like Lockheed’s MQ-25 it was also a flying wing with a similar configuration, although it was designed to be stealthy along the lines of the other defunct UCLASS competitors.

Still, the company went as far as mounting a Cobham refueling pod on one of two X-47B airframes that were already paid for and tested. Couldn’t Northrop Grumman just have simplified and tweaked the X-47B’s design anywhere possible on paper to save on unit cost while using the existing X-47Bs as proof of concept demonstrators?

It is somewhat hard to imagine that the Navy would buy a totally notional aircraft—or one that hasn’t even flown before—over one that is a derivative of an aircraft that has already been tested on a carrier.

Regardless of Northrop Grumman’s possibly nearsighted move to step away from the MQ-25 tender, Lockheed has put forward some very impressive art. But the fact that they didn’t invest in a prototype is another sign that confidence in this program making it to production may be low.

We have long posited that resistance to fielding advanced unmanned tactical aircraft is destructively palpable on a social level within the USAF and even the Navy. According to our sources close to the Navy’s pilot dominated aircraft procurement decision making apparatus, this program has little actual support.

Additionally, at this point in time there are no funds to buy more than four MQ-25s over the next four years. So even if the four pre-production examples get built, they could end up becoming a tiny experimental testing fleet onto themselves unless additional funds actually materialize.

If this proves to be true, building and presenting a paper airplane to the Navy instead of a far more expensive real one sure makes a lot of business sense.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com