Though there was never any real doubt, more than a decade later, the Israeli government has finally acknowledged that the country was responsible for destroying a secret Syrian nuclear reactor and declassified a number of details, along with video and images, about the intelligence process and the complex air strike itself. This decision seems to have been a response to a confluence of factors, including the present situation in Syria, renewed debate about Iran’s controversial nuclear program, and domestic political rivalries.

On March 21, 2018, Israel lifted its gag order on official statements about the mission, officially called either Operation Orchard or Operation Soft Melody, but also referred to within the country’s military as Operation Outside the Box. We now know for sure that at least eight aircraft took part, including four F-15I “Ra’am” (Thunder) from the Israeli Air Force’s 69 Squadron and four F-16I “Sufa” (Storm) each from 119 and 253 Squadrons. On the night of Sept. 5-6, 2007, the planes streaked through Lebanon and across nearly the full length of Syria and dropped approximately 17 tons of precision guided bombs on the reactor building, nicknamed “Rubik’s Cube” or just “the Cube,” before heading north and departing the area via Turkish airspace.

“The nuclear reactor being held by Assad would have had severe strategic implications on the entire Middle East,” the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) said in an official statement, according to Defense News. And given that the site was in a remote part of Syria’s still hotly contested eastern Deir ez-Zor Governorate, “the security implications of a nuclear reactor falling into the hands of [ISIS] or other extremist groups during the war in Syria are vast.”

An intelligence puzzle

The roots of the 2007 mission trace directly back to at least 2004, when Israel’s Mossad national intelligence agency and IDF military intelligence elements began picking up spotty reports about a potential Syrian nuclear program and foreign specialists helping with that effort. According to various

Israeli and international media reports that have now emerged, the Israeli intelligence community spent the next year going back and forth about what to make of this information.

There were indications that the Syrian government had been interested in acquiring nuclear weapons for decades, dating back to the regime of Hafez Al Assad. But long-time Syria analysts within the Israeli government reportedly questioned whether his son, Bashar Al Assad, who took over the country after his father’s death in 2000, would really push ahead with this project.

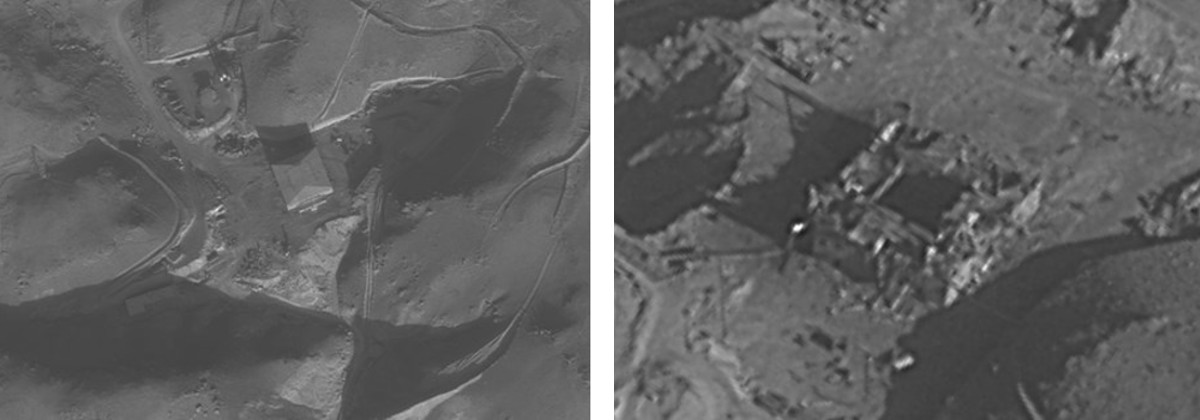

This debate raged on even after satellite imagery revealed the existence of the Cube at Al Kibar in Eastern Syria in April 2006. There was nothing else near the building and though its obscure location seemed to clearly indicate a desire to hide it from prying eyes, there was little verified information about what was inside. The eventual construction of a pipeline further pointed to a cooling system for a nuclear reactor, but again there was no corroborating evidence.

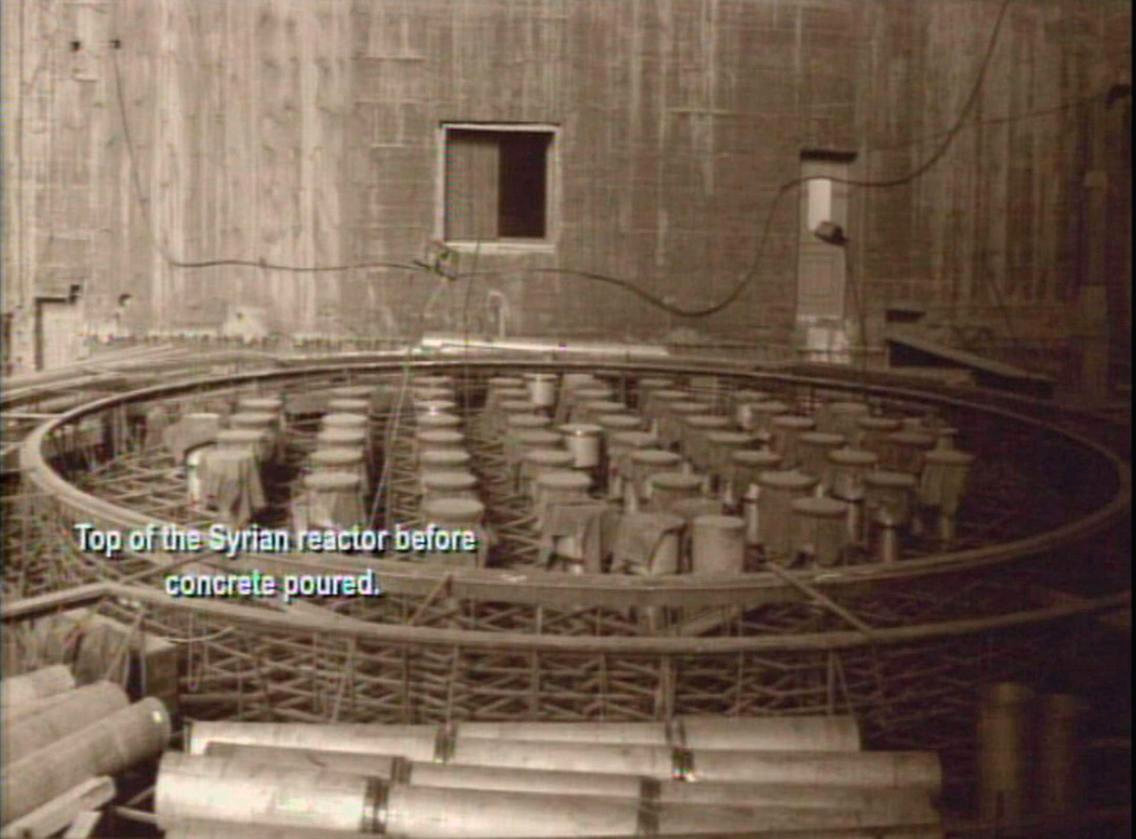

The big break came in 2007, when Israeli agents obtained actual photographs of the reactor under construction inside the building and what appeared to be North Korean specialists working at the site. How this actually occurred is one of many details about how Israel first uncovered the Syrian nuclear project and the operation to destroy the facility that remain state secrets.

However, a 2012 report in The New Yorker says this happened because of a glaring lapse in judgment by Ibrahim Othman, the head of the Syrian Atomic Energy Commission. On a trip to Vienna Austria in March 2007 to attend a meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) Board of Governors, Othman, for reasons that remain unclear, was carrying a laptop with the images and host of other highly sensitive information. Mossad agents reportedly broke into Othman’s Austrian home while the Syrian official had stepped out for one of the IAEA’s gatherings and scraped everything from his computer.

“A team of Mossad agents succeeded in bringing the information in the way that it knows how. Other than that, I won’t elaborate,” former Mossad head Tamir Pardo said at a conference on March 21, 2018. “It was pure luck that this group of agents succeeded in bringing this information.”

Pardo was at the gathering to honor the memory of his predecessor Meir Dagan, who was in charge of the spy agency as it gathered information on the Syrian reactor and in the lead up to the actual attack in 2007. Dagan died in 2016.

A hidden reactor

The new information confirmed without any doubt that the Syrians were building a nuclear reactor and that it was doing so with help from North Korea. In addition, the design mirrored the one at Yongbyon, which the North Koreans used to produce fissile material for nuclear weapons, strongly indicating its purpose was to support a larger weapons program.

That information did not apparently make deciding what to do any easier, though. As Israeli intelligence agents and analysts had picked apart Syria’s nascent nuclear efforts, the country had found itself in a brief, but violent conflict with Hezbollah, a Lebanese militant group that receives support from both Syria and Iran, in Lebanon.

The fighting had exposed serious issues with the IDF’s readiness, shown Hezbollah to be a capable fighting force, and generally proven to be a debacle for a government led by an already unpopular Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. Israeli authorities would subsequently release a damning review of the operation that bluntly described it as having failed to achieve any appreciable objectives.

With this experience in mind, and IDF reforms still underway, there were serious questions about whether the country could counter to any retaliation from Syria, or even its proxies such as Hezbollah, in response to an attack on the reactor complex. Beyond that, Olmert had brought in former Prime Minister Ehud Barak to serve as his defense minister after reshuffling his cabinet in the aftermath of the conflict and the relationship between the two men did not turn out to be a positive one.

To this day, the two former leaders offer contradictory accounts of how they ultimately arrived at the decision to blow up the reactor building. Though he expertly declined to name names, ex-Mossad chief Pardo said the success of the final operation was clouded by a “war of egos.”

As a result, in the weeks prior to the strike, Israeli officials discuses a number of different options, including publicly outing Syria’s nuclear program, privately approaching Assad through intermediaries, or some type of military operation. They even met with then U.S. President George W. Bush and members of his administration on the matter, hoping the U.S. military might be able to take care of the matter and assume responsibility for the aftermath.

The Bush administration, still smarting from intelligence failures with regards to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, declined to take part. The U.S. intelligence community agreed with their Israeli counterparts that the Cube was a covert nuclear reactor, but without any information about an active nuclear weapons program to go along with it, reportedly viewed it as a low priority issue.

The Israelis disagreed. In 1981, then Prime Minister Menachem Begin had made it state policy that Israel would not allow any potential enemies to threaten the countries destruction with nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction. That year, the IDF launched another successful mission to destroy Iraq’s nuclear reactor at Osirak, codenamed Operation Opera.

Planning the strike

How to best launch the strike remained open for debate. The Israelis felt that giving Assad space to plausibly deny that the Cube was actually a North Korean-designed nuclear facility could help reduce the possibility of a response. A small, swift strike, would also limit the chances of the Syrians viewing the operation as the prelude to another all-out war.

“I wasn’t worried about operational success of the attack, but about the danger of it triggering a war,” Israeli Air Force Major General Amos Yadlin, who was head of the IDF’s main military intelligence arm at the time and had actually been among the pilots who carried out the 1981 strike in Iraq. “Syria could have launched 100 missiles at us the following morning and we would have been in an entirely different situation.”

Added to these concerns was the fact that the longer Israel spent trying to craft the perfect plan, the more likely it was that the Syrians would add actual nuclear fuel to the reactor and that it might become operational. If that happened, there would be the added risk that a strike might create a radiological disaster.

There was also a danger that leaks in the press or elsewhere might reveal the extent of Israel’s knowledge about the Syrian nuclear program and prompt Assad to fortify the area with his best air defenses, making the operation even riskier. In the end, news that a U.S. journalist had begun asking questions about Syria’s reported work in this area pushed the Israeli government to approve the operation.

Much about the mission itself remains classified. The four F-15Is and four F-16Is carried various precision-guided bombs, including bunker busters. The decision to use this mix of aircraft, carrying what appears from official videos and images to be both laser- and GPS/INS-guided munitions, was to provide redundancy and flexibility in order to ensure that there would be enough ordnance to fully destroy the site and that the pilots could hit their mark regardless of any environmental or other factors. Laser-guided weapons are generally more precise, but clouds, dust, and other obscurants can block the beam and throw them off course.

And though the F-15Is and F-16Is are optimized for long-range missions with conformal fuel tanks and underwing drop tanks, the task force did also include aerial refueling tankers. These aircraft likely orbited in the Mediterranean to help the jets make their final sprint home after leaving Turkish airspace.

Many details remain classified

But intelligence and electronic warfare assets, among others, would have had to play an essential part in both the mission planning and execution. There’s just a low chance that eight fourth generation Israeli jets without any low-observable features would have been able to zip across Syria, even at low altitudes, and then out through Turkey without either country being aware of it.

Turkish authorities reportedly only knew the aircraft had exited by way of their country after some of the planes jettisoned their drop tanks. It was highly embarrassing for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who then still had good relations with Israel and had not gotten advance notice of the operation, and prompted an official apology from Prime Minister Olmert.

It is widely believed that Israel disrupted or disabled Syrian air defense and communication systems using a computer program known as Suter, which BAE Systems had first developed for the U.S. Air Force. Different versions of this system reportedly allow the user to monitor enemy radar information or even take control of those systems to actively misdirect or disable them.

There are also reports that unmanned aircraft may have been involved in the mission. These drones could have surveilled the site in the lead up to the strike or helped provide bomb damage assessments afterwards to confirm the site’s total destruction.

Whatever the case, the operation was successful, with pilots reportedly relaying the codeword “Arizona” across the radio to confirm the strike had destroyed the reactor site. Israeli authorities then issued the gag-order on details about the mission, even censuring Benjamin Netanyahu, who’s Likud party was then chief among the country’s political opposition, for releasing too much information. Netanyahu had implied to the press that he had been the one to push Olmert to action.

Given what became known as the “zone of denial,” Assad was able to claim falsely that his air defenses had chased off the attackers, who had been unable to cause any substantial damage. It almost quickly became clear, however, that the almost certainly Israeli strike had leveled a covert nuclear reactor. IAEA investigations starting in 2008 provided public evidence that the Syrians had been running an undeclared nuclear program.

Subsequent satellite imagery of Al Kibar showed Syrian authorities had first erected another structure to cover the remnants of the reactor site and had then dismantled much of the equipment before the area steadily fell into the hands of first the Al Qaeda-linked Al Nusra Front in 2012 and then came under ISIS control. U.S.-backed Arab and Kurdish forces now occupy much of Deir ez-Zor Governorate.

Why declassify the operation now?

That Israel’s connection to the strike was well established, if unofficially, and that there is no real question about the existence of Syria’s nuclear program or its connection to North Korea, does raise questions about why the country has decided to acknowledge this operation now. The most obvious reason would be to send a signal to Syria, Iran, and any other potential opponents that Israel remains able and willing to respond to such threats.

“The message of the attack on the reactor in 2007 is that Israel will not accept the construction of a capability that threatens the existence of the State of Israel,” IDF Chief of Staff Lieutenant General Gadi Eisenkot said in a statement. “That was the message in ’81 [with the strike in Iraq]. That was the message in 2007. And that is the message to our enemies for the future.”

You can watch IDF Chief of Staff Eisenkot’s full statement below:

Israel might feel it is important to reiterate the Begin Doctrine given that Assad appears to be firmly in power in Syria, thanks almost entirely to his Russian and Iranian benefactors, even if it’s debatable how much control his regime actually exerts throughout much of the country. This stability, and the protection he’s afforded especially by Russia’s involvement in the country, definitely appears to have emboldened the Syrian military to continue its brutal and indiscriminate assaults in rebel-held areas.

These operations continue to include chemical weapons despite very public threats from the United States and other countries. There are also reports about continuing and potentially increasing North Korean and Iranian connections to Syrian advanced weapons programs, including chemical agent and ballistic missile production.

Beyond the immediate area, there is a very real possibility that the United States may abrogate the international deal with Iran over its nuclear program. As a candidate and President, Donald Trump has repeatedly criticized the agreement, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and his administration took a newly hard line on the issue in 2017.

The War Zone has already written in detail about the JCPOA and the debate surrounding its effectiveness, which you can find here. Whatever the deal’s actual merits, there is a real concern that without it, Iran could decide to push ahead with building nuclear weapons.

Israel has reportedly actively considered striking Iranian nuclear sites in the past, but has previously acquiesced to U.S. government pressure not to do so unilaterally. The Trump administration could be far more accommodating if Israeli officials were to contemplate such an operation again in the future, especially if the Iran deal collapses. Releasing information about the 2007 strike could help Israel make sure the regime in Tehran understands that those threats are and remain credible.

But there’s no real indication that there is any debate about Israel’s willingness to defend itself in this regard. Since Syria descended into civil war in 2011, Israeli aircraft have struck targets in the country, particularly those linked to Hezbollah, on multiple occasions.

More recently, the Israeli Air Force has extended those strikes to include more regime targets, including those potentially full of Iranian or Iranian-backed forces. And in line with the Begin Doctrine, Israel has struck sites linked to Syria’s chemical weapons and other advanced weapons projects.

This doesn’t include operations further afield since 2007, either. In 2009, its jets reportedly flew all the way to Sudan in order to destroy arms bound for the Palestinian militant group Hamas.

These sorts of operations have long been a core component of Israeli foreign policy and the ability to do so was driving force in the country’s push to transform its early F-15s into long-range, multi-role combat aircraft more than four decades ago. Four years after the mission to Osirak, Israel employed those jets to fly down the Mediterranean and attack the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s headquarters outside Tunis in Tunisia.

And Israeli aircraft has conducted the operations in Syria despite threats from Assad and risks to its own personnel. In February 2018, in response to an Iranian drone entering Israeli airspace from Syria, Israel launched air strikes that resulted in the loss of multiple aircraft to Syrian air defenses.

An ongoing “war of egos”

In actuality, domestic politics might be bigger driving force behind Israel’s decision to declassify details about the operation. On May 14, 2018, the country will celebrate the 70th anniversary of its founding and the 2007 strike reflects one of the most important and successful foreign policy decisions the country has faced in the last 30 years.

On top of that, the IDF might be keen to present its own version of the facts ahead of the publication of dueling memoirs from Ehud Olmert and Ehud Barak, which are set to come out later in 2018. The two men continue to spar over their respective records and vehemently and publicly disagree about who had taken what position over the Syrian nuclear issue.

This “war of egos” likely extends to Benjamin Netanyahu, who is now Israel’s Prime Minister, is a harsh critic of the Iran Deal, and happens to be under investigation for corruption. He is also considering calling snap elections, which some accuse him of using as way to deflect attention from the probes into his business dealings.

“I am not sure it was right to release information about this operation now,” former Mossad Head Pardo said. “Maybe eight years ago, or maybe eight years from now.”

Whatever the exact reasoning behind the release, it can only send yet another message to Israel’s potential opponents that it does remain very willing to launch complex and risk strikes in response to existential threats. It’s almost certain we will continue see more such Israeli operations in Syria, and potentially elsewhere, in the future.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com