Following Russian claims that it is developing a new nuclear-powered cruise missile, there are reports that the U.S. government has been actively spying on this work and that some or all of the test flights have failed. This, in turn, raises questions about the safety and viability of such a weapon, as well as why American officials would keep this knowledge a secret.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin publicly announced the as yet unnamed missile in an annual speech on March 1, 2018. The Kremlin says it successfully tested one of the weapons near the end of 2017 and released video footage claiming to show the launch and it in flight. So far, Russian authorities have not released any other significant details about the weapon’s configuration or capabilities, though Putin implied that the final design would be broadly similar in size and shape to the existing, conventionally-powered Kh-101 cruise missile.

At the most basic conceptual level, the weapon could conceivably reach supersonic speeds, fly at very low altitudes, and have effectively unlimited range thanks to its nuclear powerplant, allowing it to hit targets anywhere in the world with little warning and dodge anti-missile defenses.

But shortly after Putin’s address, CNN, in a story citing an anonymous U.S. government official, cast doubt on the possibility that this weapon was anywhere near operational. That individual added that the “United States had observed a small number of Russian tests of its nuclear-powered cruise missile and seen them all crash.” Fox News said its own sources indicated the same thing, that the weapon was in the research and development phase and that at least one had crashed during testing in the arctic.

The suggestion the U.S. government has been aware of this development program for any period of time, but kept that information secret, is notable in of itself. American officials have often shared knowledge publicly, even if only in broad terms, about other similar Russian advanced weapon projects, especially to make the case for increased spending on ways to directly or indirectly counter those weapons.

In a routine press conference on March 1, 2018, top Pentagon spokesperson Dana White declined to comment on the record about whether or not any of the weapon systems Putin announced were operational. She did, however, insist that none of them were new.

“These – these weapons that – that are discussed have been in development a very long time,” she said. “Our [new] Nuclear Posture Review takes all of this into account.”

President Donald Trump’s Administration’s new Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), which it officially released in February 2018, mentions Russia’s hypersonic boost glide vehicle development, as well as its nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed unmanned undersea vehicle project, commonly known as Kanyon or Status-6. There is no discussion of a nuclear-powered cruise missile.

An unclassified report on worldwide cruise and ballistic missile programs that the U.S. Air Force’s National Air and Space Intelligence Center released in June 2017 makes no mention of a nuclear-powered cruise missile either. It does discuss Russia’s work on a hypersonic boost glide vehicle.

It’s even more curious that the United States would have chosen to stay silent if it was aware of failed flight tests involving the prototype missiles. They would, by definition, have to carry a nuclear reactor, and any accidents could pose health and environmental risks, not just for Russian civilians, but potentially for residents in other nearby countries, as well.

Given heightened tensions between the two countries over a wide array of different issues, including compliance with strategic arms control agreements, one has to imagine that this would have given the U.S. government an excellent opportunity to further criticize the Kremlin’s general attitude toward its own people and its neighbors.

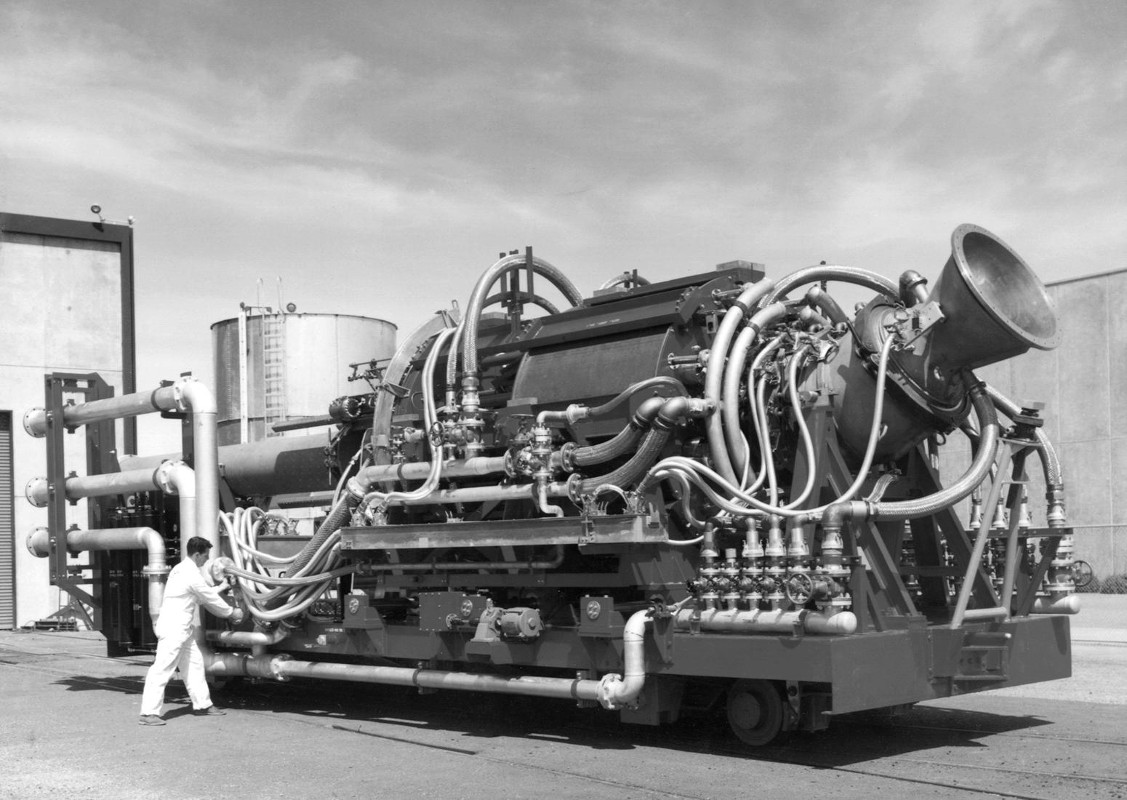

And the U.S. government is well aware of the potential hazards of nuclear-powered engine designs, having experimented with these systems extensively in the 1960s. The U.S. Air Force had even explored the possibility of developing a Supersonic Low Altitude Missile (SLAM) with a nuclear-powered ramjet that sounds very similar in basic concept to the weapon the Russians say they are now developing.

The United States subsequently concluded that while the engines technically worked, they simply did not offer a practical means of powering a ground- or air-launched weapon and could have provoked an arms race with the Russians. To make the reactors small, light, and cheap enough to ride inside a notional expendable missile, the prototype reactors lacked protective shielding and emanated dangerous levels of radiation. The proposed weapon, which never progressed to the prototype stage, would still have been 13 feet high at its tallest point and 52 feet long, nearly as high as and longer than an F-16 Viper fighter jet.

In flight, the engine would have left a trail of radioactive byproducts in its wake, potentially contaminating any area it flew over, enemy-controlled or not. The scientists and engineers behind the project suggested that this could have been a terrifying added feature rather than a flaw.

To be fair, reactor technology has significantly improved since the SLAM project ended in 1964. On top of that, Russia has invested significant manpower and resources into development of smaller nuclear power sources to help support expanding civil and military activities near and above the Arctic Circle, though there are significant concerns about whether these systems are reliable and safe.

But it doesn’t change the fact that a nuclear-powered cruise missile will be carrying some amount of radioactive material and that the Russians almost certainly do not expect it to survive the trip, even when it works properly. It’s worth noting that what the U.S. government has recorded as “crashes” may be flight tests the Russians have deemed successful. Russia would have to test the weapons repeatedly in order to prove the design is reliable, especially as testing matures and the prototypes’ flight envelopes expand.

And if Russia has completed any test of a functional prototype system, albeit without a live nuclear warhead, this means it has almost certainly deliberately smashed a live nuclear reactor into the ground or the sea at high speed. The very idea of doing this, even for tests purposes, helps explain why the United States never actually flew a prototype aircraft or missile using nuclear propulsion.

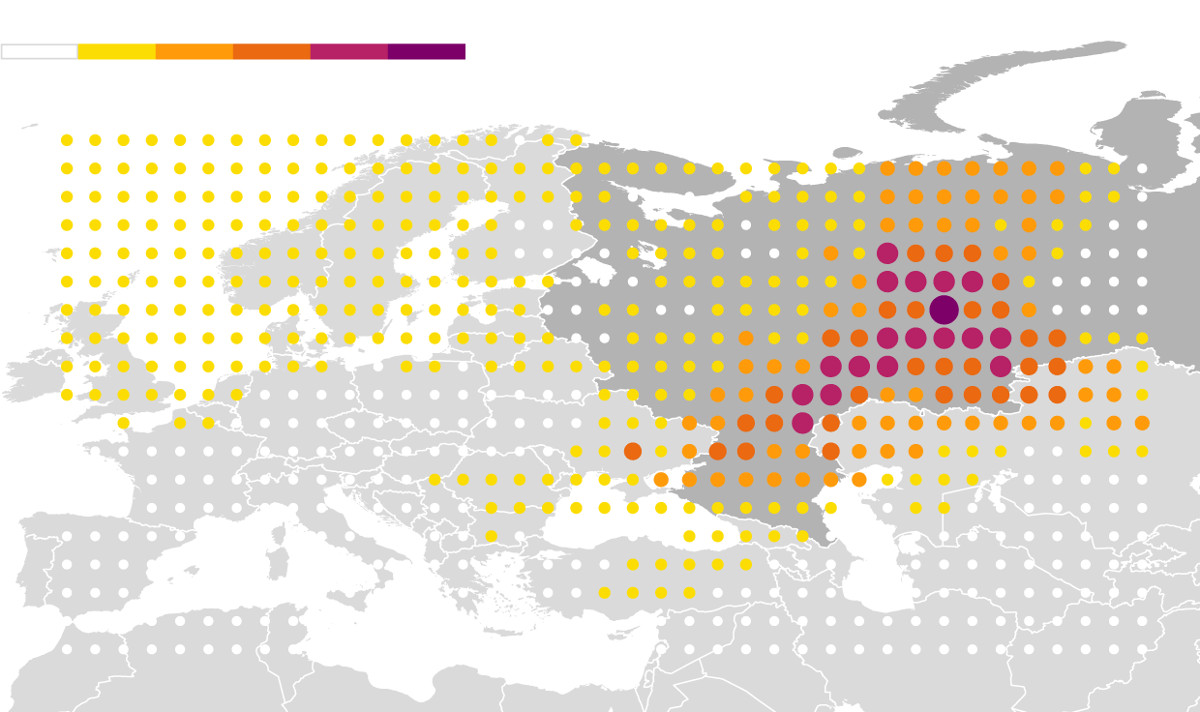

As such, Russian flight tests of the weapon, successful or not, might offer one explanation about reported spikes in the amount of radioactive iodine-131 in the atmosphere appearing to originate from Russia’s northwestern Kola Peninsula on the Barents Sea in February 2017. This isotope is among the dozens of radionuclides that the Department of Energy recorded as being a byproduct from nuclear engine tests at the Nevada Test Site between 1959 and 1969.

Around the time of this reported radiation release in Europe, the U.S. Air Force deployed one of its limited number of WC-135W Constant Phoenix aircraft to the region. These aircraft carry specialized equipment collect air samples in order to detect signs of possible nuclear activity.

On Feb. 20, 2017, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization, which monitors compliance with the 1996 treaty of the same name, subsequently issued a statement saying that it had not detected any elevated levels of iodine-131 “in the past several months.” “If a nuclear test were to take place that releases I-131 it would also be expected to release many other radioactive isotopes.”

One would also expect a nuclear ramjet to produce a wider array of nuclear byproducts, but it might do so at levels far too small for sensors set up to look for nuclear explosions to detect. According to the Department of Energy, the experimental Tory IIC nuclear ramjet released less than 1,000 Curies of radiation during a five-minute test in 1964. If that rate had remained constant, even if that engine had run for 24 hours straight, it would have produced less than one percent of the the typical radioactivity associated with the detonation of a one kiloton nuclear weapon.

The Air Force also subsequently denied that WC-135 mission had anything to do with any increase in iodine-131 in the atmosphere and said that it had scheduled the deployment well before those reports emerged. “We just need to make sure that we’re getting the background and knowing what’s happening around the world and what changes are happening in the atmosphere,” U.S. Air Force’s Colonel Jonathan VanNoord, Director of Operations for the Air Force Technical Applications Center (AFTAC), told Stars and Stripes in March 2017.

Still, AFTAC is a particularly secretive organization that officially exists primarily to monitor whether countries that have ratified the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty are abiding by the terms of that agreement. It also helps gather intelligence about other nuclear tests and also helps gather information after atomic accidents. And since it already appears that the U.S. government’s knowledge of the nuclear-powered cruise missile program is itself classified, there would be no way VanNoord could have admitted his crews were hunting for signs of the weapon.

In September and October 2017, there were reports of increased levels of radioactive ruthenium-106, also tracing back to Russia. This isotope is now among those the Department of Energy linked to its own nuclear engine work, but those tests did produce ruthenium-103 and -105. Experts suggested this incident could have been a leak from the Mayak nuclear fuel reprocessing facility.

With all this in mind, it remains unclear why the U.S. government has held back in exposing this project, but they may have been waiting for a more opportune moment. Unlike other systems, its not as clear cut whether the nuclear-powered cruise missile violates existing U.S.-Russia arms control agreements, such as the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF.

That agreement bans Russia and the United States from building production land-based cruise missiles that have ranges between 310 and 3,100 miles. Its not obvious how the treaty would necessarily apply to a missile with unlimited range. At the same time, the INF does not explicitly prohibit research and development of land-based cruise missiles that would otherwise violate its terms, a loophole the United States itself has announced its intention to exploit.

The U.S. government could be trying to gather enough data to more conclusively demonstrate that the Kremlin released dangerous amounts of radiation with these experiments, too. Russia may not have actually test flown the prototype missile with a nuclear reactor on board, using a surrogate conventional engine arrangement instead, though this is unlikely. This would be the only reasonable way for the Russians to launch the weapon without any possibility of releasing of radioactive material, but it would also largely defeat the purpose of such tests.

But now that the existence of the program is out in the open, we may soon see more Russian boasts about its capability and American criticisms regarding its safety.

Programming note: Our analysis of the air-launched hypersonic missile revealed by Putin during his speech is up and can be found here. It turns out that the mysterious weapon is far more familiar than most probably think.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com