The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the U.S. military’s top research arm, is looking into whether it might be possible to exploit fish, shellfish, and other marine organisms as unwitting sensors to spot and track submarines and other underwater threats. The idea is create a low cost means of persistently monitoring naval activity beneath the waves across a wide area, but it could be hard to get the sea life to reliably perform their new jobs as discreet undersea spies.

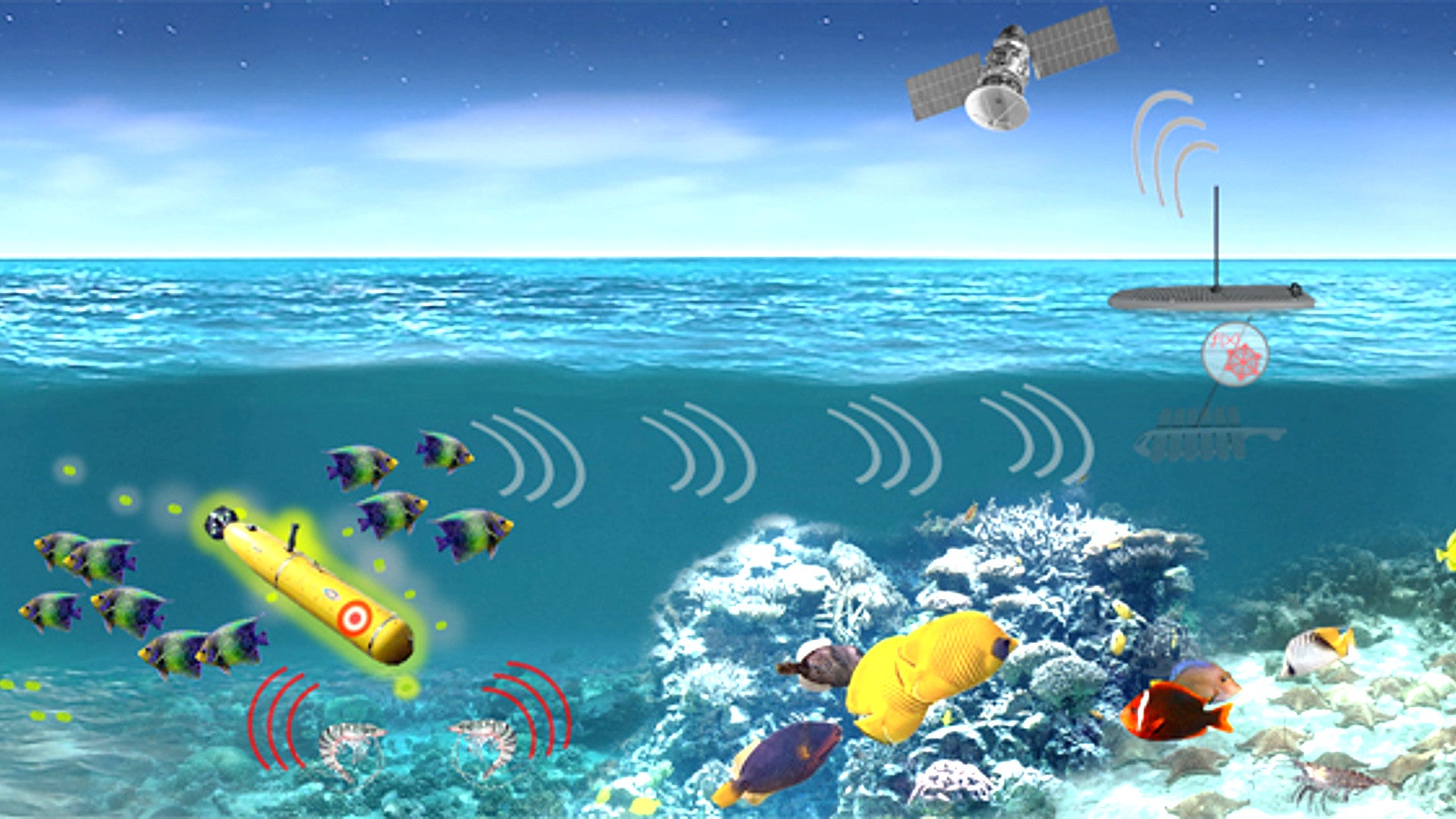

DARPA first announced this project, which it calls the Persistent Aquatic Living Sensors, or PALS, earlier in February 2018. The month before it had unveiled a broader concept for an “Ocean of Things,” which would also incorporate a large number of small, low cost, and environmentally friendly sensor nodes, either on the sea bed or floating up above, to monitor ship and submarine movements, as well as gather data about changing environmental conditions and other scientific information.

“The U.S. Navy’s current approach to detecting and monitoring underwater vehicles is hardware-centric and resource intensive,” Lori Adornato, the PALS program manager, said in an official statement. “If we can tap into the innate sensing capabilities of living organisms that are ubiquitous in the oceans, we can extend our ability to track adversary activity and do so discreetly, on a persistent basis, and with enough precision to characterize the size and type of adversary vehicles.”

At the most basic level, DARPA envisions developing a system that records marine animal activity, or the sounds they produce, and decodes that data to determine whether they’re just swimming along as normal or dodging an enemy submarine. This would not require actually implanting or otherwise “modifying” any fish or crustaceans.

“Our ideal scenario for PALS is to leverage a wide range of native marine organisms, with no need to train, house, or modify them in any way, which would open up this type of sensing to many locations,” Adornato added. DARPA notes that marine animals are otherwise already equipped, thanks to millions of years of evolution, to have the “equipment” necessary to monitor their own environment. Beyond just being able to see, touch, and hear potential prey or threats, they can often detect more subtle electro-magnetic and chemical changes to their surroundings.

This could all make the system more cost effective, since the U.S. military would only need to establish a network to collect the relevant information, categorize it, and transmit it onward to wherever it might need to go. DARPA’s goal is for each of those nodes to be able to monitor fish and other sea life more than 500 yards away and to be able to reliably discern between routine and abnormal movements and sounds.

It’s ambitious, but PALS could offer a novel solution to the U.S. Navy’s very real problem of trying to adequately monitor the movements of potentially hostile submarines or underwater drones across broad areas, especially in the Pacific Ocean. Advanced diesel-electric subs with air-independent propulsion (AIP) technology are only becoming more common and affordable, even to smaller countries.

AIP systems let conventional submarines sail more quietly and remain underwater for extended periods of time, offering capabilities closer to that of nuclear submarines, but without the costs and other factors associated with those boats. Among America’s potential near-peer opponents, China actively pursuing expanded submarine capabilities, including both nuclear and AIP-equipped submarines. At the same time, the country is looking to improve its own abilities to track American submarines in the Pacific through underwater sensor networks.

Russia is also slowly adding advanced diesel-electric submarines as it overhauls its existing fleet, while North Korea is steadily growing its own capabilities in this regard to potentially include designs capable of firing nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. Russia and China are also pushing their boats on the open market, and North Korea often collaborates with other potential opponents of America, all of which could put advanced designs into the hands of smaller, regional adversaries.

To handle these emerging threats, the Navy is already exploring the potential of using long-endurance unmanned surface craft to scour the open ocean semi-autonomously for threats. Unfortunately, existing unmanned undersea vehicles operating with limited human interaction far from friendly forces have proven vulnerable to harassment and capture. Forward deployed ships, manned aircraft, and drones, all offer additional maritime surveillance capabilities, but require significant manpower and logistical resources, as well as often complicated basing agreements with host countries.

It is possible that the Navy could look to link those more traditional assets with a working PALS system in the future in order to extend their capabilities. This in turn could help them narrow their search area or make it more difficult for a hostile submarine to elude its pursuers after an initiation detection.

But leveraging sea life has the potential to eliminate many of those considerations entirely. Unfortunately, PALS’ objectives are likely to be easier said than done.

This is hardly the first time the U.S. military, including DARPA and its predecessor organizations, have investigated the possibility of employing local fauna to spot and track enemies with limited human interaction. Those past projects have almost universally failed to produce the results.

The biggest issue is that without some sort of control mechanism, animals are, well, animals. They can behave unexpectedly or erratically and their basic habits can change as they age or in response to broader changing environmental factors. The same species of fish or invertebrate might not even manifest the same characteristics in different areas of the ocean, a problem that emerged in a previous Navy program to turn whale songs into a covert communications tool.

Any sensor system collecting information about them will have to account for these things in order to avoid routinely sending back false positives. DARPA will need to run a wide array of tests with various species just build an initial dataset of the kind of responses it can expect when a submarine or other man-made underwater object passes by those creatures.

It’s a lot of potential clutter for any system to try and parse through quickly. Advances in artificial intelligence might be able to help speed up the process of identifying patterns of activity and correlating them into actionable information in the future, something the U.S. military is working on already as a way to help sift through bulk intelligence imagery.

This lack of readily uniform results has stymied a number of earlier animal-based military projects, including the U.S. Army’s attempts to develop what it called “instrumented biosensors” during the Vietnam War. The basic idea was to build a hand-held device full of insects that would become agitated when they became exposed to air with traces of human sweat or waste. The operator would listen for increased buzzing or clicking through a set of headphones. The plan was to use the units to detect ambushers and as “people sniffers” to track insurgents hiding in dense jungle environments.

Needless to say, it didn’t work. The bugs didn’t always respond when the researchers hoped they would, or, more problematically, just did so in response to being shaken around as soldiers carried the prototype systems. As living organisms, they also had normal rest and activity schedules that meant they would regularly stop “working” entirely for extended periods of time.

DARPA has left open the possibility of “modifying” fish or other sea creatures with some additional equipment, such as miniaturized sensors, to help improve the reliability of any such system. This could easily prove politically controversial and the Navy already routinely fields criticism from environmental advocates that its operations, especially the use of active sonar, endanger whales and other aquatic animals.

Doing so would also likely limit the cost saving aspects of PALS, since it would require capturing the animals, installing the necessary components, and releasing them back into the wild. To make the system work at all, the U.S. military will already need to deploy and maintain the sensor net to process and transmit the data.

It would also limit the life forms that the U.S. military would be able to use at all. “DARPA expressly forbids the inclusion of endangered species and intelligent mammals, such as dolphins and whales, from researchers’ proposals on the PALS program,” Jared Adams, a spokesperson for the agency, told Defense News. The Navy does use dolphins and sea lions to help hunt for underwater hazards and other items of interest, but in conjunction with human handlers.

If DARPA can find a way to make PALS practical and reliable, it could definitely be a boon for the Navy’s ability to locate potentially hostile submarines and other undersea threats. Unfortunately, past experience shows that there are already a number of challenges the project will have to overcome first.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com