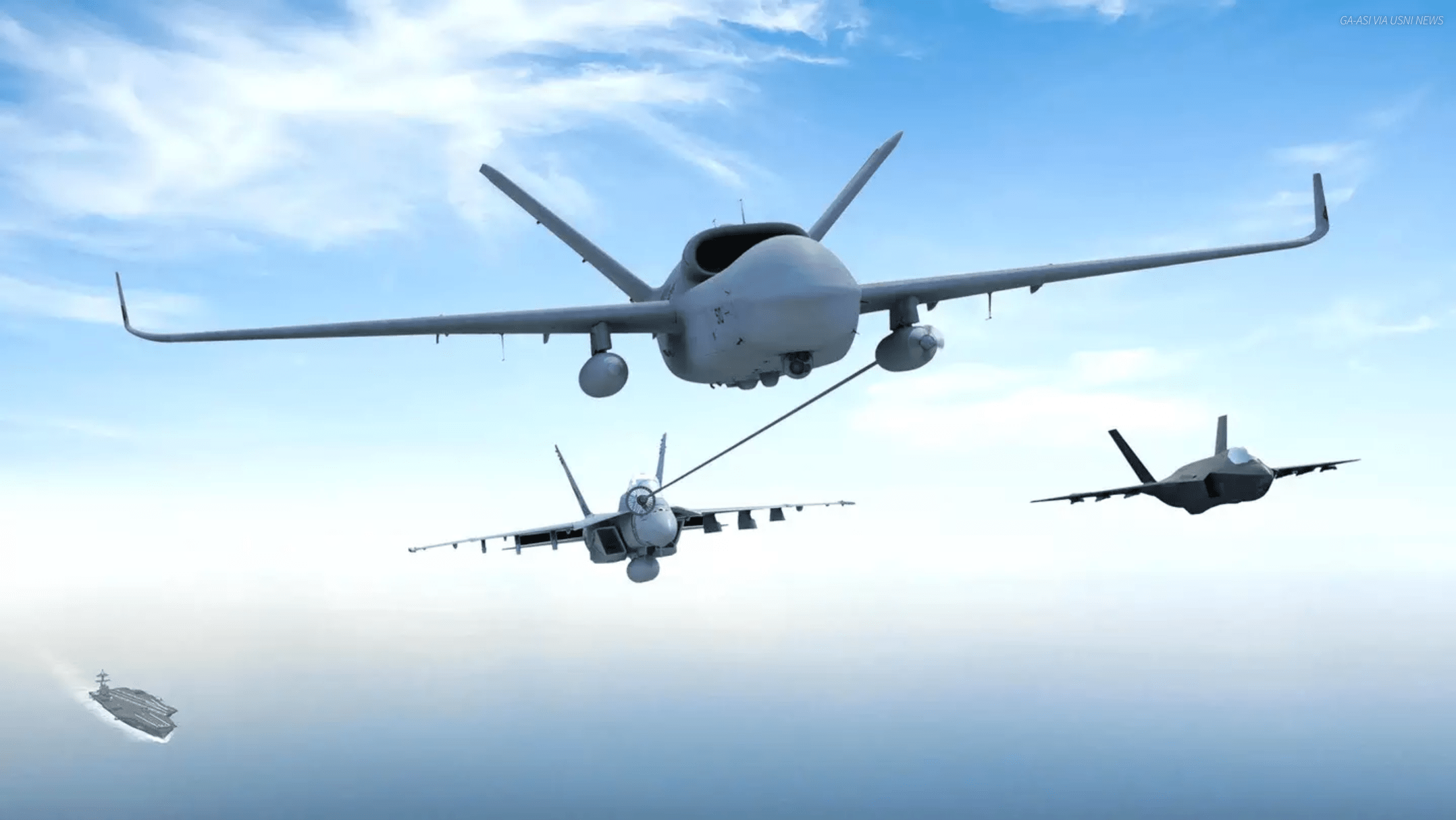

General Atomics has announced it will team up with Boeing to compete for the contract to build the first four MQ-25 Stingray carrier-based tanker drones for the U.S. Navy if it wins the competition, though the latter firm says it will also pursue its own individual proposal, as well. This follows the service dropping something of a bombshell in its latest budget request, stating that, at best, it will only buy four of the Stingrays over the next six years and that a possible larger buy of 68 will only come some time after that, if it happens at all.

After we wrote this article Tyler Rogoway talked with General Atomics about their partnership plans and their MQ-25 contender. Our findings from that interview are included at the bottom of this piece.

On Feb. 12, 2018, General Atomics revealed the partnership with Boeing in a press release that also named a half dozen other companies that it would be working with on its MQ-25 bid. Pratt & Whitney will supply its PW815 high bypass turbofan engine, UTC Aerospace systems will design the landing gear, L3 Technologies will be responsible for the satellite and line-of-sight control and data links, BAE Systems will craft portions of the unmanned aircraft’s software, Rockwell Collins will provide its AN/ARC-210 radio, and GKN Aerospace’s Fokker division is on hand to design and build the arresting hook.

In a statement to The War Zone, Boeing said this arrangement would not stop it from submitting its own proposal to the Navy, meaning that the General Atomics’ led group will still be up against Boeing and Lockheed Martin. Northrop Grumman decided not to compete for the Stingray contract in October 2017.

“As the world’s premier quick reaction unmanned aircraft system manufacturer, we are committed to delivering the most effective, affordable, sustainable, and adaptable carrier-based aerial refueling system at the lowest technical and schedule risk,” David Alexander, President of General Atomics, said in the press release. “We look forward to supporting GA [General Atomics] with our aviation and autonomous experience.” Boeing Autonomous Systems Vice President and General Manager Chris Raymond, added in the same statement.

It’s not clear what this could mean for the team’s final MQ-25 proposal. General Atomics had been first to show concept art of a full design, which looked to be a derivative of its Sea Avenger concept that it had proposed to the Navy as part of its earlier Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) program. Boeing had been the first to present a semi-functional full-scale prototype with an entirely different planform, notably including some stealthy features, including a rare flush dorsal jet intake, and the company will continue development of that design separately.

In another statement to The War Zone, Boeing said that it would not disclose any specifics about its present working relationship with General Atomics, but that it would likely refine the exact details of its partnership if its competitor wins the competition. Boeing had previously demonstrated semi-autonomous unmanned aircraft operations with its X-45-series and the Decision Mission-Control software, or DICE, in early to mid-2000s. But if nothing else, Boeing brings decades worth of experience working with and supplying aircraft to the Navy.

The Chicago-based plane maker reportedly sees the competition as a “must win” situation and this arrangement would give them a chance to be involved at least to some degree even if they lose out to General Atomics. We don’t know how this could impact Lockheed Martin’s proposal, which so far has not been made public to any serious degree.

The General Atomics’ industry team also makes perfect sense given the Navy’s very public push for competitors to use as many commercial-of-the-shelf and otherwise existing components and technologies as possible in order reduce risk and shorten the aircraft’s development cycle. The Navy’s approach of buying a very small number of MQ-25s initially for a firm, fixed price does indeed mitigate some risks, chiefly ensuring the design is fully functional before proceeding with a larger purchase order.

At the same time, that the field of competitors for the MQ-25 seems to keep shrinking isn’t surprising, either. The problem with the Navy’s present course of action plan, as we at the War Zone have noted before, is that it might be less risky for the service, but potentially much more so for any company interested in building the aircraft.

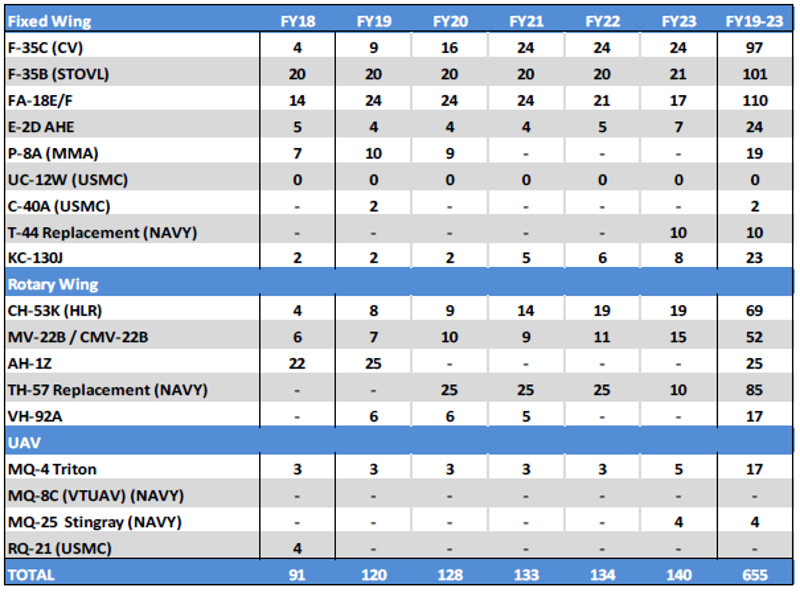

If the firms competing for the Stingray deal had any concerns about the project’s viability, the Navy will have only magnified them by establishing a painfully slow schedule for the project, which it outlined when it released its budget request for the 2019 fiscal year on Feb. 12, 2018. Though it plans to award the initial MQ-25 engineering and development contract by the end of 2018, a chart in a briefing the Navy showed to members of the press at Pentagon noted that it only expects to have four MQ-25s in its possession by 2023. This is in line with a plan U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Mark Darrah, the head of the unmanned aviation and strike weapons program office at the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR), first disclosed in November 2017.

But tucked away in the proposed budget’s fine print, a more detailed explanation says the “objective” time frame for the Stingrays to reach initial operational capability is 2024, but that might end up delayed until 2026. How four MQ-25s represents an operational capability of any kind is unclear. The Navy has said this is the minimum number for a single, complete unmanned system, which allows for one aircraft to be on station, another heading out to take up the refueling orbit, and other returning to the carrier to refuel itself, with a fourth drone in reserve.

More importantly, it says that the firm or firms that win the initial contract won’t have to build all four aircraft up front, stating that the funds – all of which are in the research and development portion rather than the procurement section – will support work on just two “demonstrator model” prototypes, which are only supposed to have their first flights by the end of 2021.

If there’s one positive in the line items for the MQ-25 in the Navy’s fiscal year 2019 budget proposal, which it now describes simply as “Unmanned Carrier Aviation,” or UCA, is that the drones should have a built-in persistent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capability from the start. A series of reports

in 2017 suggested the Navy was looking to water down the MQ-25’s capabilities even further and either scale down or eliminate the drone’s secondary intelligence gathering mission.

“MQ-25 will be designed to conduct aerial refueling and ISR missions,” according to the budget request documents. “Sensor data will be transmitted at appropriate classification levels, to exploitation nodes afloat and ashore.”

Unfortunately, at present, the firm or firms that win the MQ-25 engineering and development contract would get a guaranteed order of just four aircraft over at least the next six years, and possibly longer. That need to commit significant time and money up front developing an unmanned system that the Navy might not ultimately buy at all in significant numbers – the service says it reserves the right to abort the project and start again if the drones don’t live up to expectations – is likely a major reason why Northrop Grumman dropped out of the competition entirely.

And this six-year schedule is only if the program continues as planned. As noted, the actual delivery schedule calls for the contractor to supply just half the already tiny number of aircraft within three years. With how many times the Navy’s unmanned carrier projects have morphed over the past decade, its not hard to imagine shifting priorities yet again in a three to six year time frame. The social realities within the naval aviation community with regards to a future full of high-end unmanned aircraft flying from carrier decks is also a glaring issue few like to discuss.

The Navy has already been publicly working on developing a major carrier-based unmanned aircraft capability for around two decades, having initially paired up with the U.S. Air Force on the Joint Unmanned Combat Air Systems (J-UCAS) program in the early 2000s and subsequently kicking off its own Unmanned Combat Air System Demonstrator (UCAS-D) project. Between 2011 and 2015, the service extensively evaluated a pair of Northrop Grumman X-47B drones, including tests showing off revolutionary autonomous carrier landings and takeoffs and the pilotless planes’ ability to link up with an aerial refueling tanker.

That was supposed to be a precursor to a fully fledged program to develop a fleet of stealth, deep-penetrating strike and reconnaissance drones as part of the UCLASS program. The Navy eventually changed those requirements entirely and shifted the drone’s primary focus to acting as an unmanned flying gas station, known as the Carrier-Based Aerial-Refueling System (CBARS), to support a carrier air wing’s manned aircraft, which has now become the UCA program. It’s a saga you can read about in depth in this detailed feature by The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway here.

Now the service is pushing the possibility of having a useful MQ-25 fleet even further into the future. This is all especially notable since senior service officials have made comments in public stressing the already pressing need to free up up Super Hornets from the job of acting as smaller aerial tankers for the rest of the carrier air wing. This is added to the increasing strain on Super Hornets across the Navy in general.

In October 2017, U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Mike Shoemaker, the service’s top aviation officer, made the shocking announcement that only just more than 30 percent of the service’s Super Hornets were ready for combat at any given times and approximately 50 percent of the total fleet was airworthy at all on average. On top of those abysmal availability numbers, the Navy estimates that a the Super Hornets a carrier can get into the air spend between 20 and 30 percent of their time on refueling.

The Navy does want to buy 110 additional Super Hornets over the next five years, with 24 in its budget request for the 2019 fiscal year, but that wouldn’t obviate the clear benefits of the MQ-25, even if it’s a far cry from the potentially game-changing capabilities the proposed stealthy UCLASS drones would have given each carrier air wing. The Stingrays would still free up more F/A-18E/Fs for combat air patrols and strike missions and extend the overall range of those force packages. The latter point is only becoming more important as both near-peer and smaller potential adversaries continue to expand the range and scope of their defense networks, which could force a carrier to launch its aircraft from further away in order to better shield itself from enemy counter-attacks. The MQ-25 will

“We’re going to move forward with our strategy,” Rear Admiral Darrah insisted in November 2017. “[We] feel we’re in a good position with whoever remains behind to give us a proposal.”

The question now is when that strategy might actually produce the results the service needs already.

Update:

After talking with General Atomics MQ-25 program manager Chuck Wright and communications manager Melissa Haynes we got a clearer view as to why the company paired with Boeing, one of its primary competitors for the MQ-25 tender, as well as what we can expect from their UCA design.

Wright made it clear that in his opinion Boeing is going forward with the pairing because it increases their chances of some sort of a win when it comes to the MQ-25 competition, stating “winning the whole thing is great, but a slice of a team is also great too.” Considering Boeing apparently sees this as a must win for them, hedging by agreeing to work with General Atomics if they are victorious does make good sense.

During our conversation, Chuck Wright laid out a number of reasons why General Atomics saw it as beneficial to add Boeing to their MQ-25 team. These included the fact that Boeing has a large unused facility that would be well suited for producing the MQ-25—a major expense saved if General Atomics were to win the MQ-25 competition—and that it could also potentially facilitate the production of other systems in the future. Boeing highly diverse manufacturing expertise was also not lost on General Atomics.

The fact that Boeing has a long standing relationship with the Navy and has huge experience particularly in the systems integration, aircraft test and evaluation, and carrier suitability space is seen as a huge benefit should General Atomics get the shot at executing on their MQ-25 proposal. As Wright put it, Boeing has a “well deserved reputation for knowing what needs to be done” when it comes to bringing a naval aviation program through to fruition, especially one that has to operate in the confines and harsh environment of an aircraft’s carrier’s deck and hangar bay.

Above all else, the two defense contractors have been talking for years about how and when to cooperate on new mutually beneficial projects, and General Atomics’ MQ-25 initiative seemed to suit the bill nicely.

As for the company’s MQ-25 prototype itself, which we have only seen in artists renderings as of yet, it is slated to be unveiled in just two months.

Like all the UCA competitors, General Atomics had worked hard on developing an aircraft to satisfy the Navy’s earlier UCLASS requirements, which was for a more advanced penetrating reconnaissance and strike unmanned aircraft. Then the seagoing service canceled that set of requirements in favor of an unmanned tanker with much more limited surveillance capabilities and no strike or penetrating abilities at all. As such, its design emanates from the Sea Avenger UCLASS concept, which itself was a derivative of the stealthy Predator C/Avenger land-based unmanned aircraft that has been flying for years.

But it’s not like General Atomics UCA entrant is just an Avenger with a tailhook and a buddy refueling pod slapped on it. The highly altered design came to be thanks to advanced software tools where engineers could reconfigure nearly limitless iterations of the basic design based on many variables and requirements.

Since the Navy wants the aircraft to “carry a lot of fuel, a long ways” as Wright put it, major changes like a much more voluminous overall design and more efficient powerplant came into play. Wright says the General Atomics engineers built a lot of margin into their design as well and really optimized it as best as possible to meet the UCA mission.

With all this in mind, we’ll just have to sit tight for a couple of months to see General Atomics’ MQ-25 in the flesh for ourselves.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com