As the U.S. military rolls out its budget request for the 2019 fiscal year, one area that is likely to see newly increased attention is the development and purchase of land-based anti-ship weapons. The U.S. Army is already planning to sink a target ship with a truck-mounted anti-ship cruise missile in a major exercise as concerns grow about both near-peer and smaller states expanding their ability to control strategic waterways around the world, especially China’s militarization of the South China Sea.

In January 2018, Navy Recognition confirmed that the Army would fire at least one Naval Strike Missile (NSM) at a decommissioned ship from a launcher on the back of a 10×10 Palletized Load System (PLS) truck during Rim of Pacific (RIMPAC) 2018, a massive annual U.S.-run international maritime drill that typically occurs near Hawaii in the summer. It’s not clear whether or not the launcher is on a self-contained pallet, but such an arrangement could allow the vehicle to either fire it after moving to a specific location or unload it so troops have established a temporary fixed launch site. Poland already fields a land-based version of the NSM, but using a different type of truck. Norwegian firm Kongsberg designed the NSM, which it now builds in cooperation with American defense contractor Raytheon.

“We think that the emphasis on cross domain and bringing all shooters together in a distributed fashion to mass on a target or targets provides a wonderful opportunity, we are just really excited about it,” Gary Holst, Senior Director of Business Development at Kongsberg told Navy Recognition at the Surface Navy Association’s 2018 National Symposium in Washington, D.C.

“The missile, no matter where you shoot it from, can hit moving targets at sea or can hit a target stationary ashore so it is designed from the get go to be a cross domain capable weapon,” Tom Copeman, Vice President of Business Development at Raytheon Missile Systems Air Warfare Systems division, added.

The NSM is primarily a sub-sonic, sea-skimming anti-ship cruise missile that can hit targets up to 100 miles away. It uses a combination of GPS, inertial navigation, and terrain recognition to get the target area, then uses an infrared imaging seeker to home in on the ship in the final stages of its flight. The missile can discriminate between its intended target and other objects by running what that camera sees against an internal database of potential target types, improving its overall accuracy.

It has a terrain-following functionality that means it can fly from launch positions well inland and dodge mountains, hills, and other similar obstacles, even before it gets to the open water. As such, it also has a secondary land-attack mode, making it a multi-purpose weapon that could further expand Army capabilities.

On top of that, it uses composite materials and low-observable design features to better hide it from enemy sensors as it approaches the target area. The NSM also makes random course changes during its terminal flight phase to make it more difficult for close-in weapon systems to shoot it down.

The video below shows a live-fire test of an NSM from a ship-mounted launcher.

The U.S. Navy is already actively considering the missile as an option for a variety of ships, including its planned new class of frigates. Relatively easy to install deck-mounted launchers mean the service might be able to quickly add them to existing Littoral Combat Ships, amphibious ships supporting U.S. Marine expeditionary operations and maybe even logistics vessels and sea bases. A follow-on development, the Joint Strike Missile, could be a future option for the U.S. Air Force’s F-35A and Navy’s F-35C Joint Strike Fighters, as well as other foreign countries operating the A variant.

But a mobile, land-based version of the system would give the Army an anti-ship capability that it has lacked in any form for decades. The service shut down its Coast Artillery Corps entirely in 1950, shifting the focus of those units to air defense.

This made a certain amount of sense at the time, with the U.S. military having a dominating presence on the world’s oceans and there being a very limited threat to American coastlines from enemy surface warships. At the same time, China, Russia, and other potential adversaries who have had concerns about such attacks developed or otherwise acquired increasingly advanced shore-based anti-ship weaponry.

And since the end of the Cold War, though, that United States’ clear naval advantage has steadily eroded, especially in the Pacific where China has dramatically improved both the size and capabilities of its surface fleets as it expands it territorial claims in regions such as the South China Sea and East China Sea.

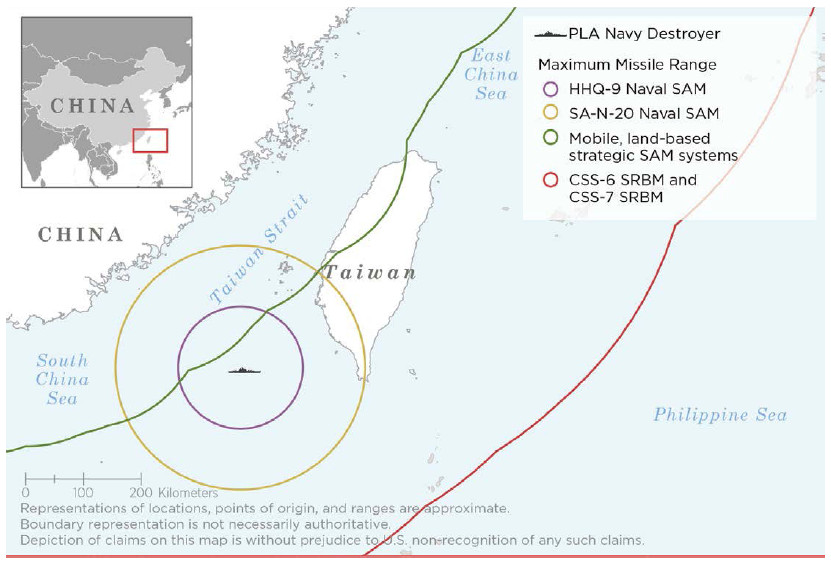

In a crisis, Chinese aircraft carriers, advanced destroyers, and other warships, could be an important components of the country’s ability to control large maritime areas and deny its opponents access. On top of that, China’s military is increasingly boasting an array of other formidable anti-access and area denial capabilities, including its own-shore based anti-ship missiles, advanced manned and unmanned aircraft, ballistic missiles, surface-to-air missiles, and long-range sensors.

Taken together these dense defensive networks could present a significant challenge to American operations in the Pacific. They could easily limit the ability of U.S. forces to maneuver using traditional sea- and land-based capabilities, including the U.S. Navy’s own aircraft carriers and overseas territories such as the island of Guam, which is host to vitally strategic port and air base facilities. They could similarly slow the U.S. military’s ability to respond if an ally, such as Taiwan, came under attack.

Land-based anti-ship missiles and associated land-based sensors, including sea search radars, would give the U.S. military another important option to defend its own possessions, as well as rush to reinforce allies or otherwise break through area denial threats during operations. They might even have a deterrent effect on immediate Chinese activities by forcing them to consider the limits to their own freedom of movement during a potential crisis.

“The goal to provide joint solutions between sensors and shooters at the tactical level across multiple domains, this is juice worth the squeeze,” U.S. Navy Admiral Harry Harris, head of U.S. Pacific Command, said in a speech at the Land Forces in the Pacific Symposium in Hawaii in 2017. “A forward-deployed ground force can create temporal windows of opportunity to gain superiority in multiple domains that will allow the other components to kill the enemy more effectively.”

In addition, the goal is for these mobile ship-killing weapons to eventually be able to sync up with sensor nodes across the services, including those on board ships, manned and unmanned aircraft, and even in space, to quickly locate and engage enemy targets. This broader network, which would also include non-traditional platforms such as the F-35, could add even more flexibility to Army anti-ship units by giving them access to a more distributed array of information or allowing them to engage targets well beyond the range of any organic capabilities.

Future variants of the NSM will likely have a two-way data link, meaning that various sensor nodes would be able to feed course corrections to the weapon in flight to improve the missile’s accuracy and help it dodge threats in flight. This is already a planned feature on the air-launched Joint Strike Missile.

“The end result of my challenge shouldn’t be a simple exercise where we all high five at the end and then head back to the comforts of our services,” Harris added in his 2017 speech. “Service-specific systems must be able to talk to one another if any of this is going to achieve the effects that we’re looking for. Ideally we’ll get to a point where we see the Joint Force as a network of sensors and shooters allowing the best capability from any single service to provide cross domain fires.”

That level of integration could be getting closer to reality already, especially with the Navy’s push to integrate the weapons and sensors on all of its ships, aircraft, and land based assets. The Army and other services could leverage the lessons learned with that project, known as the Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air (NIFC-CA), to develop their own systems and increase the likelihood that they would be interoperable at least to some degree from the very beginning.

Mobile anti-ship missiles would be a relatively rapidly deployable capability, too. In addition to give American forces more freedom to maneuver and given the NSM’s land-attack option, the Army might be able to send launchers to allied or partner countries in the South China Sea, such as The Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, or Vietnam, and potentially hold some of China’s island outposts at threat directly. The Army, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps, already trains with the U.S. Air Force to rapidly deploy the M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) to remote or forward areas.

These so-called HIMARS Rapid Infiltration (HIRAIN) exercises often involve loading one of the truck-mounted launchers into a C-17 transport, flying it to a forward base, offloading it, and then having the vehicle’s crew either simulate or live-fire an actual rocket right from the tarmac. This same concept could work with wheeled anti-ship missile launchers to provide a rapid anti-ship defense anywhere in the world on relatively short notice.

The video below shows a HIRAIN exercise at Kunsan Air Base in South Korea in 2017.

Foreign partners could also join with the United States on developing and procuring such systems, which could help share the cost burdens. Japan is already slated to join the Army in the shore-based missile attack on the target ship during RIMPAC 2018 and is working on new air-launched land-attack cruise missiles in part to defend against increasing Chinese incursions in the East China Sea.

And NSM is likely to be only one component of the Army’s anti-ship arsenal, as well. When it first became clear that the service was interested in getting back into the ship-killing mission in 2016, the immediate plan was to give existing Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) missiles, which have a range of 190 miles, a moving target capability.

This program is still ongoing and would make these short-range quasi-ballistic missiles another possible anti-ship weapon. The Army can load one ATACMS into its wheeled M142 HIMARS and two into each of its larger M270 tracked Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) vehicles.

In addition to NSM, Raytheon is in the process of developing the replacement for ATACMS as part of the Long Range Precision Fires program. It is very possible that those missiles, known as DeepStrike, could easily have a similar anti-ship capability as the modified ATACMS from the start.

The Marine Corps is interested in acquiring an anti-ship missile system that will fit in the HIMARS launcher, as well, and could join with the Army in its development efforts, further sharing the burden of development and procurement costs. In 2017, the Marines demonstrated the ability to launch a standard 227mm guided artillery rocket from the deck of an amphibious ship using one of the truck-mounted systems, another employment concept that could be similarly impressive with a vehicle armed with ship-killing weapons.

In November 2017, the Army also expressed an interest in buying the Serbian Advanced Light Attack System’s coastal defense variant, or ALAS-C, though it’s not clear whether those purchases would be for its own use or for foreign military sales. In 2013, the United Arab Emirates announced their intention to team up with the manufacturer EDePro, by way of the Serbia’s state-run Yugoimport SDPR arms broker, to build a light truck-mounted launcher using the 6×6 Nimr chassis.

ALAS-C is wire-guided, but has an impressive range for a missile of this type, able to hit targets between 15 and 30 miles away. It has a man-in-the-loop guidance system where an actual operator steers it on its target in the terminal phase by way of an infrared camera in the weapon’s nose.

The Israelis have been pioneers of this concept, which improves the accuracy, especially against moving targets and gives an actual person the ability to abort the attack very late in the missile’s flight in case of concerns about collateral damage or civilian casualties. ALAS at its core is actually very similar to Israel’s Spike-ER anti-tank missile, but has considerably greater range.

If the Army did procure ALAS-C or a system like it, though it has relatively small warhead, it would offer another way of destroying smaller boats or landing craft. This level of anti-ship system could be useful for defending against more limited threats in constrained waterways, such as Russian missile-armed corvettes in the Baltic Sea or Black Sea or small Iranian watercraft and mining ships in the Strait of Hormuz.

With a combination of NSM, anti-ship ATACMS or new Deep Strike missiles, and a short-range system such as ALAS-C, the Army could field a tiered, mobile anti-ship defense system that can engage a variety of different maritime threats. These systems could offer defense in depth at existing locations or the option of rapidly deploying the most appropriate weapon in case of a particular contingency.

The Army, along with its sister services, will almost certainly continue to iron out the exact requirements and concepts of operations for the different weapon systems in the coming months. As the number of potential threats continue to grow, the service won’t be able to wait too long to begin procuring and fielding this long neglected, but increasingly important capability.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com