A man whose quick and bold thinking likely saved the world from a nuclear disaster has died. The Barents Observer reports that Igor Grishkov, the 67 year old retired Russian Navy captain, passed away in Severodvinsk, located along the frigid White Sea. Grishkov had lived there since retiring from the Russian Navy.

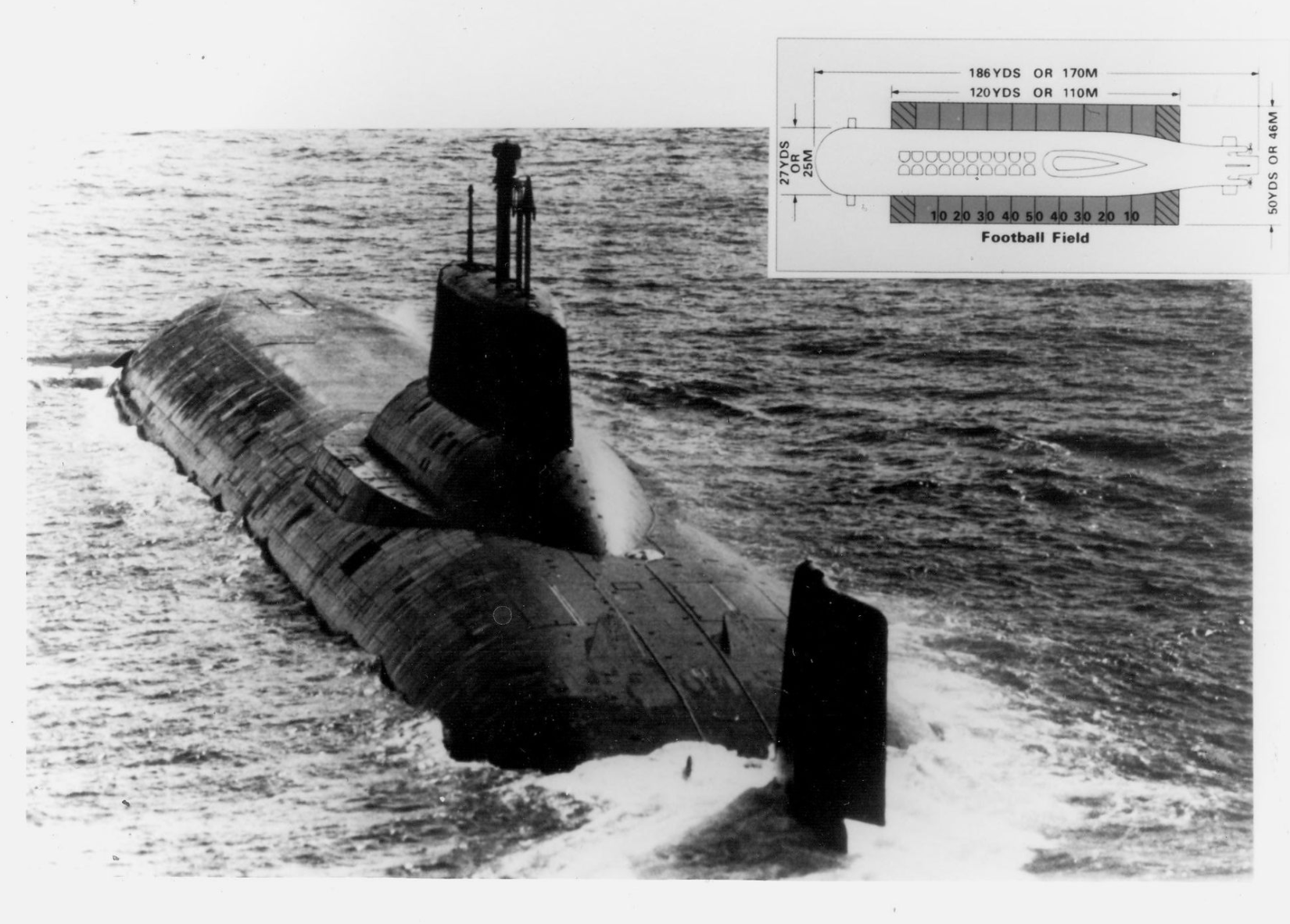

27 years earlier, then Captain Grishkov was in command of one of six of the deadliest weapons the Soviet Union ever created, the massive Typhoon class nuclear ballistic missile (SSBN) submarine TK-17. It was during the most turbulent time in Russian affairs since WWII when TK-17 slunk beneath the waves in the White Sea, not far from the place of his death, that Grishkov was faced with one of a nuclear submariner’s worst nightmare scenarios.

The near catastrophic event remained deeply classified for decades, but today we have a decent idea of what happened on that fateful day in September of 1991.

TK-17 was ordered to execute a test launch of one of its 20 SS-N-20 Sturgeon (locally called the R-39 Rif) submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Like their host submarine, these three-stage solid-fuel ballistic missiles were absolutely massive in size, weighing a staggering 185,000 pounds and able to carry up to ten multiple independently-targeted reentry vehicles (MIRVs).

A test missile, which had inert warheads, was loaded into one of TK-17’s vertical launch tubes before the submarine headed out to sea. Once launched, it would fly thousands of miles east, impacting on Russia’s missile range on the Chukotka Peninsula. The exercise was largely a display of continuity, strength, and stability to a world which had just witnessed a failed coup attempt against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. In reality, the Soviet Union was in a state of collapse, and by Christmas of that same year it would disintegrate in full.

Foreshadowing events to come politically for the USSR, the test launch turned into a harrowing failure. On September 27th, 1991, TK-17 moved into launch depth position and ran through its pre-firing sequence. As the launch clock clicked down towards zero, instead of the 53 foot long, 23 foot wide missile boosting its way towards the ocean’s surface it exploded while still cocooned inside its launch tube. The silo door that covered the missile tube was totally blown off.

The submarine shook violently and alarms rang—it seemed as if the TK-17 was doomed. Such an event would be horrific for the boat’s crew, but the loss of control of the vessel’s twin nuclear reactors and the live nuclear weapons it carried could result in a nuclear incident of massive proportions. In essence, the loss of a Typhoon class SSBN was the sum of Soviet Navy’s fears.

Grishkov acted quickly and decisively, ordering up an emergency blow of TK-17’s ballast tanks, a move that would send the 574 foot long submarine porpoising to the surface.

The action was completed successfully and TK-17’s crew was able visually examine the submarine’s long forward-set missile farm. What they saw wasn’t good. There were a series of fires raging near where the test missile had detonated.

The missile’s solid fuel propellant had scattered across the submarine’s upper surface. The rubber anechoic coating that helps the submarine from being detected acoustically was set alight and the fire would rapidly spread. 19 other missiles sat tightly packed in two neat lines of ten under and near the blaze.

Heat and ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads are a bad combination.

Once again, Captain Grishkov acted quickly and decisively, ordering a counter-intuitive maneuver for a submarine that is damaged in ways that crew couldn’t fully understood at the time.

Dive! Dive! Dive!

His plan was to put the fire out in a way only a submarine can, by submerging the vessel and starving the flames of oxygen. Grishkov knew that the stricken missile’s launch compartment would flood, and possibly other sections nearby, and alerted the crew to this possibility, but he had to make a decision that would save the boat from sinking, even if it meant taking on new types of damage and even possibly casualties.

The crew carried out the snap order far quicker than it could normally have been accomplished. When the boat was ordered back up to the surface again the fires were extinguished. The plan had worked and TK-17 wouldn’t become the embarrassment of a crumbling empire or the cause of an international crisis and environmental catastrophe.

The stricken submarine and its crew of 160 limped back to Severodvinsk where its burnt skin and badly damaged launch tube were repaired under a shroud of secrecy. The tube would never be used again and was permanently sealed off. TK-17 would go onto serve for 13 more years before being sidelined in 2004.

Grishkov was never pronounced a Hero of Russia or given an award for staving off disaster, the impact of which is hard to fathom, especially at such a turbulent time in Russian history. The Kursk tragedy nearly nine years later, which had clear parallels to the incident aboard TK-17, was controversially handled in a standoff manner by Russia, and the country wasn’t undergoing anywhere near the political turmoil as the Soviet Union was in the fall of 1991.

Would Russia have reached out for help if one of their prized Typhoon class boomers sunk? Would embarrassment and the sensitive technology held within the relatively new submarine—the most advanced fielded at the time of the incident—kept the Soviet Union from telling the world of the disaster before it was too late? How would the overthrow of the Communist Party just months later have impacted a response effort, especially if it was highly classified at the time of the political transformation?

Thanks to Captain Grishkov and his crew we don’t have an answer to those questions.

The lack of adulation towards Grishkov was largely due to the sensitive nature of the incident. Although some of the Russian Navy brass wanted to decorate him for his heroic efforts on that day, instead the powers that be chose to keep the incident secret. In turn, neither the captain or any of his crew, who all survived the incident, would ever receive the recognition they deserved.

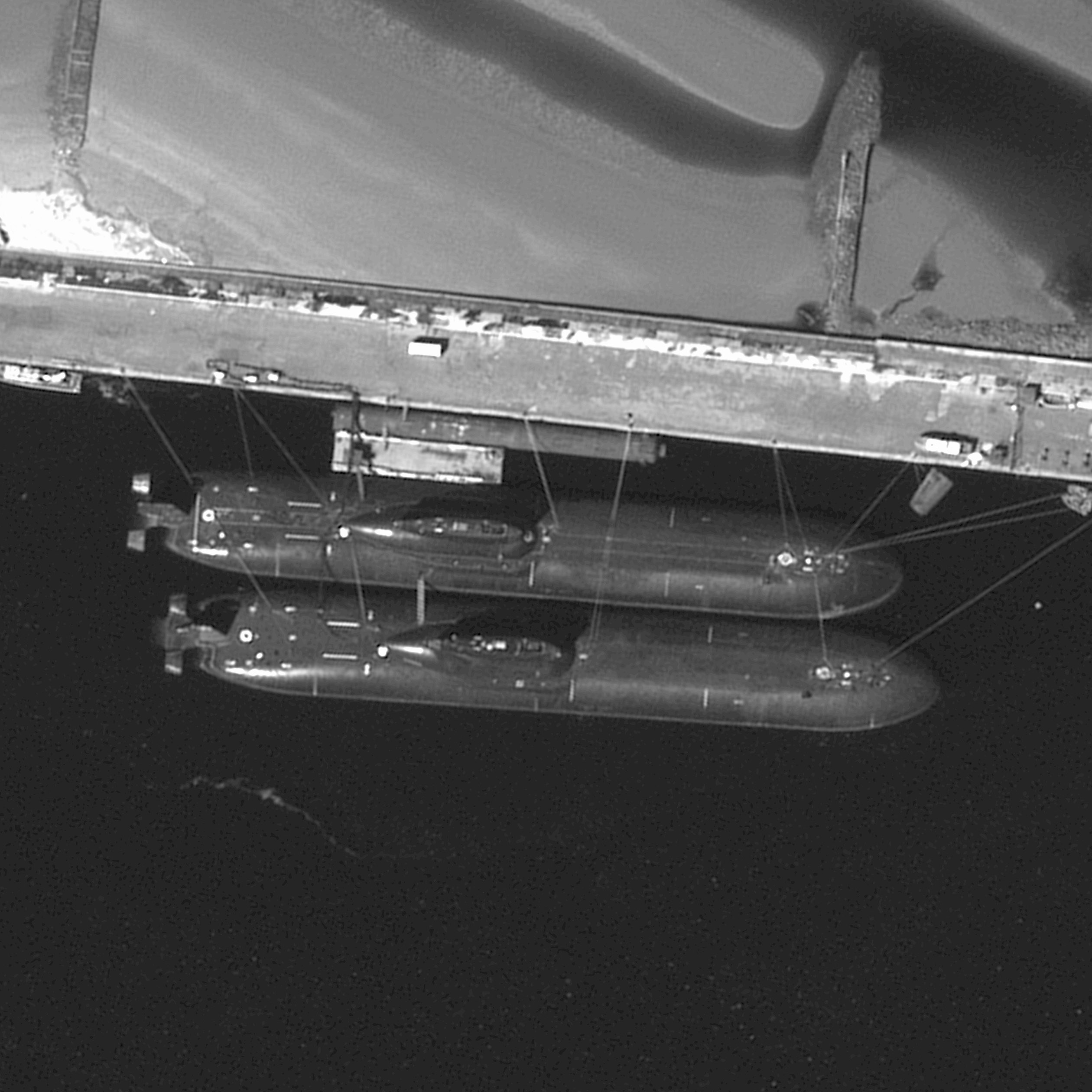

As for TK-17, the vessel has been sitting idle (take a look inside!) in Severodvinsk next to her sister-ship TK-20 awaiting decommissioning and disposal of their volatile nuclear reactors. A single Typhoon class submarine remains in Russian Navy service, the first one ever built, the Dmitry Donskoy TK-208.

It’s mission?

Submarine-launched ballisitic missile test vessel.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com