The Navy’s connection with Lakehurst, New Jersey dates back roughly a century. Today the sprawling 7,400 acre site is littered with various test facilities used to develop the latest in naval aviation infrastructure. Most notably it’s where the seagoing force perfects its catapult and arresting gear technology for its aircraft carriers. But nearly 100 years ago, Lakehurst was America’s epicenter of lighter-than-air transportation. Anchoring the base and its then high-tech mission was the absolutely massive Hangar 1, a structure that once housed the Hindenburg and stood vigil across a grass field during that famous airship’s notoriously catastrophic demise. Later Hangar 1 become the home of a little known replica of a U.S. Navy flattop named CALASSES—it remains the Navy’s largest training aid to this very day.

The 1920s was truly the age of airships, and the Navy looked to further leverage the budding technology for coastal patrol and maritime scouting duties, with a special focus on anti-submarine warfare. By 1921 the service had established Lakehurst as its headquarters of lighter-than-air technology, and it would also eventually became a hub for its related form of international commercial transportation. Hopes were high that massive dirigibles could “shrink the globe” for civilians and the military alike, and give war planners an unprecedented new mode of long-range aerial support.

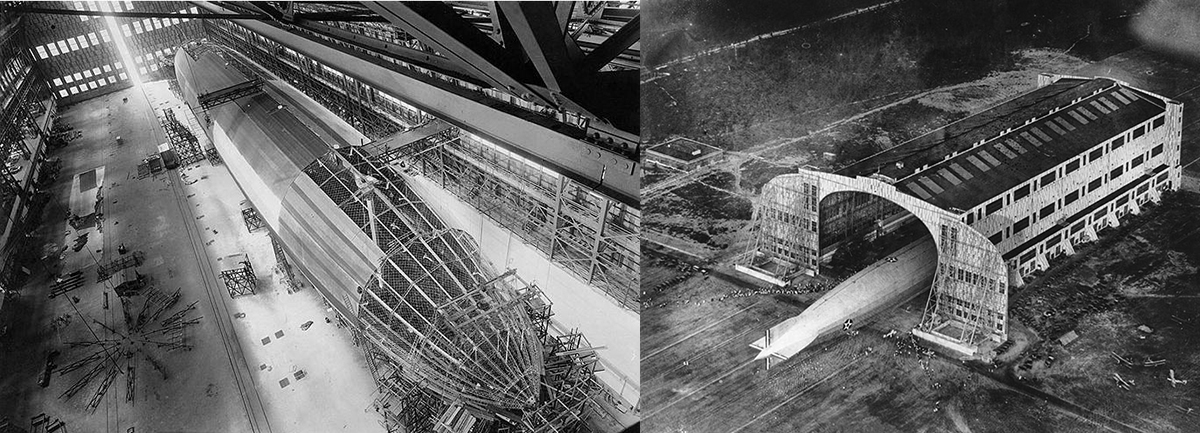

Hangar 1 was built upon the Naval Air Station’s founding in 1921. Measuring 961 feet in length and 350 feet in width, with its roofline soaring to 200 feet, the steel, wood, and asbestos-concrete structure was designed to accommodate the largest of airships and had a helium processing and delivery system nearby to service its mammoth tenants. It was also built to accommodate hydrogen-filled zeppelins as well in as safe a manner as possible. Its floor was spark-proof, electrical systems and lighting were explosion proof, among other special treatments. Volatile hydrogen was brought in via railroad tanker cars if needed.

Hangar 1’s counter-balanced doors weigh 2.7 million pounds each, of which there are four. A trolley track system ran through the hangar and out to circular mooring stations beyond to dramatically ease handling of huge airships that would call the hangar home—even if just temporarily.

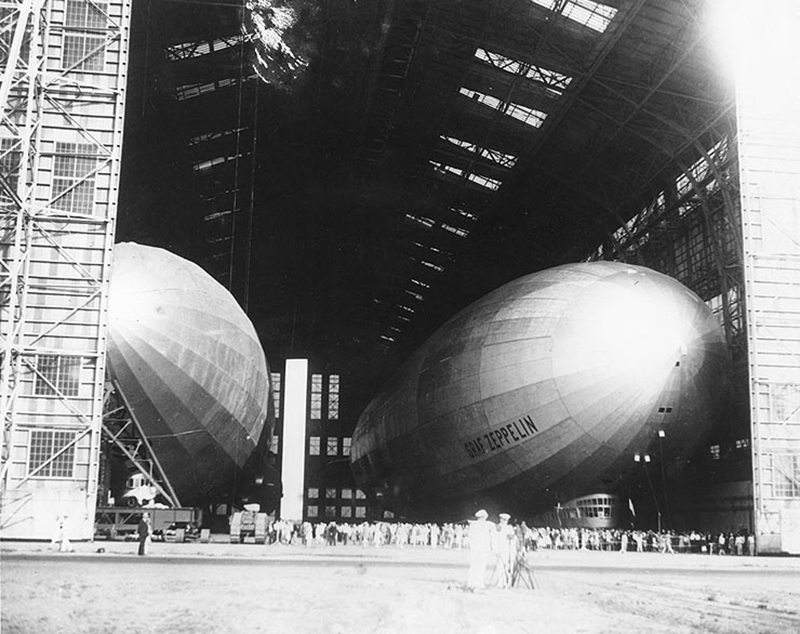

The hangar housed many of the most known airships of the era, including the first American-built rigid airship, the Shenandoah. The Navy’s hulking Macon and Akron airships had also called the base home. In fact, every one of the Navy’s relatively tiny fleet of rigid airships was based in the hangar at some point in time.

As airship testing continued throughout the 1920s, the concept of commercial air travel on airships picked up as well. Lakehurst became an international gateway for these flights. The Graf Zeppelin stopped at Lakehurst on its around the world tour in 1929, and others followed well into the 1930s, including visits by the Nazi’s Hindenburg, which only had 18 inches of clearance forward and aft when docked inside Hangar 1.

The Navy’s success with these monster aircraft was far from stellar, with nearly all of the service’s dirigibles crashing over close to a decade and a half of operations. Then in 1937, the hydrogen-filled Hindenburg took the dream of widespread commercial air travel aboard dirigibles with it as it was consumed by flames within line-of-sight of Hangar 1.

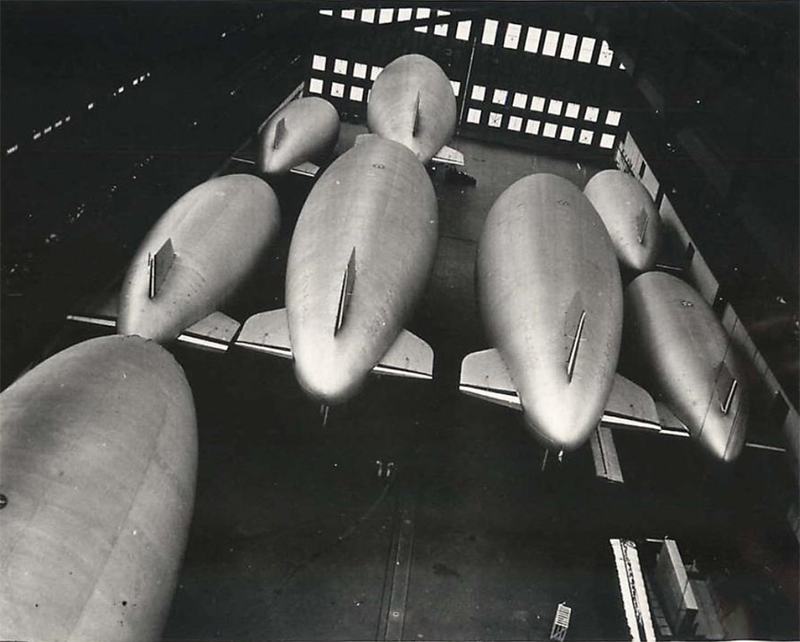

By that time the Navy’s airship program had pretty much folded, but World War II would see an airship renaissance of sorts, although those craft would be smaller anti-submarine warfare blimps, not the hulking rigid airships of the past. Still, during the height of WWII, the Navy has some 130 of these craft in service, making NAS Lakehurst a bustling place.

By the dawn of the jet age, Lakehurst was morphing from a lighter-than-air master base to one that had a wide array of uses, with testing and training become its primary missions. This included the establishment of the Naval Air Test Facility (NATF) that would evaluate aircraft carrier launch and recovery systems and other naval aviation support capabilities. This is the same high-profile mission the base primarily executes till this very day.

In 1951 the Naval Air Technical Training Center (NATTC), now called Center for Naval Aviation Technical Training (CNATT), was established at Lakehurst as well. The outfit would go on to train thousands of Boatswain’s Mates, Naval Security Guards, Marine Airfield Technicians, Aircrew Survival Equipment Men, and Aerographer’s Mates. In the 1960s a very unique training aid was developed and constructed to help in NATTC’s mission—a one third scale replica of an aircraft’s carrier’s deck.

Lakehurst was especially well suited to receive such a giant training aid as it had one of the world’s largest hangars, Hangar 1, free to shield it from the elements. By 1962 the Navy had no lighter-than-air craft left for Hangar 1 to accommodate. In other words, there was no shortage on interior space at Lakehurst to field such a large and unique contraption. And its name, the Carrier Aircraft Launch and Support System/Equipment Simulator, better known as “CALASSES,” aptly describes its mission and its size.

CALASSES is 390 feet long, with the flight-deck sitting elevated above the hangar’s floor. Underneath it are the same launch and recovery systems found on American supercarriers, including the guts of the ship’s arresting gear and catapults. Up top features everything you would find on a carrier’s deck, including an island control tower, emergency barrier rigging, arresting cables, catapult tracks, Fresnel lens “meatball” visual landing aid, and so on—all the things that are needed to train Boatswain Mates before they head out to real McCoy. CALASSES is a far more forgiving and anemic environment for trainees to learn and make mistakes compared to an actual aircraft carrier deck which is one of the most dangerous places to work in the entire world.

It’s not exactly clear when the practice ended, but for decades CALASSES operated with real airframes on its deck, along with the tractors and other equipment used to facilitate their movement and operation. The practice continued at least through the 1980s, but today no airframes are scurried around its flattop.

The funny thing is that even such a massive installation looks small in Hangar 1, with the replica carrier situated in one of the hangar’s four corners. By some accounts, CALASSES came to be at least partially as an attempt to keep the Navy from demolishing the historic structure. The idea being if the Navy’s biggest training aid—a truly one of a kind and unmovable apparatus—was built inside of it, the hangar would probably survive as long as the training aid does. Regardless if this was actually part of CALASSES’s genesis or not, both it and the historic hangar it rests under exist in good condition today.

With nearly a century of aviation history under its belt, Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst is truly a fascinating and supposedly even haunted place. The work done there over the years and today is so unique that there are seemingly unlimited stories wrapped in stories to tell. But Hangar 1 is truly the grand historical prize of the installation, and it’s only fitting that its massive facade cocoons another peculiar and massive piece of naval aviation history inside of it.

A big thank you to NAES Lakehurst public affairs and the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society for their help with this article.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com