Rumors are swirling about the fate of a top-secret spacecraft, known as Zuma, which Northrop Grumman supposedly built for an unknown U.S. government agency and launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon-9 rocket on Jan. 7, 2018. There are a number of theories about what might have happened already circulating, but a fairly obvious one seems glaringly absent: that the satellite didn’t crash at all and that it’s working as planned.

The facts as they are known are that on Jan. 7, 2018, the Falcon-9 carrying Zuma lifted off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. Space launch firm SpaceX live streamed the launch on its own website, but ended the feed early in the mission, before the separation of the second stage, due to the classified nature of the payload. The U.S. government logged the spacecraft into its catalogue of objects in outer space as USA 280, but the entry on Space-Track.org otherwise contains no details about its orbit or reentry date.

But within 24-hours, rumors and reports began to emerge suggesting that an accident had occurred and that the spacecraft was a total loss, all citing anonymous sources, with some saying that it had come down in the Indian Ocean.

Satellite watchers have so far not been able to spot Zuma in orbit, but there are also no reports of witnesses on the ground or at sea seeing an object falling into the Indian Ocean. Individuals in Sudan and flying over that country did observe what appeared to be the normal venting of excess fuel from the Falcon-9’s second stage.

SpaceX has flat-out denied that there was an issue with the Falcon-9 during the mission, but did not say anything about the Northrop Grumman-designed adapter that held Zuma in place inside the rocket’s payload fairing and would release it into orbit at the end of its launch sequence. Usually SpaceX provides this system along with the rocket, but Zuma is somewhat unique in that it used this critical component sourced from the payload’s owner—Northrop Grumman. SpaceX has similarly refused to confirm or deny anything about the status of the spacecraft due to the secrecy surrounding the project.

“After review of all data to date, Falcon 9 did everything correctly on Sunday night,” SpaceX Chief Operating Officer Gwynne Shotwell said in a statement to various news outlets by Email on Jan. 9, 2018. “If we or others find otherwise based on further review, we will report it immediately. Information published that is contrary to this statement is categorically false. Due to the classified nature of the payload, no further comment is possible.”

Northrop Grumman has said it cannot comment on the program because it is classified. The Pentagon responded to questions from various outlets saying, as a rule, that it does not comment on classified programs and could not directly address the Zuma issue. The National Reconnaissance Office has already gone on record saying that it is not the owner of the spacecraft.

At present, there are three main competing theories as to what might have happened to the payload. There may have been a problem with the payload fairing, the payload adapter might have been unsuccessful in inserting Zuma into orbit, or the spacecraft might have failed to deploy properly after the payload adapter successfully released it.

SpaceX was originally supposed to launch Zuma in November 2017. The company delayed the launch date to review concerns about the rocket’s payload fairing following the launch of another Falcon-9 on a separate mission, but did not elaborate on the issue. It is possible that whatever steps engineers took to mitigate the problem were not sufficient to prevent an accident.

The next possibility, that the Northrop Grumman provided payload adapter did not function properly, would have left Zuma stuck on the rocket’s upper stage, which then fell back to earth, burning up in the atmosphere. Some have suggested that SpaceX specifically focused its statement on the rocket successfully completing its portion of the mission, leaving out any discussion of the adapter, in order to obscure what might have happened to the spacecraft.

The last scenario involves Zuma detaching from the Falcon-9 successfully, but malfunctioning and not entering a proper orbit. Again, the theory goes that the spacecraft at least partially burned up as it fell back to earth, some sources say remnants of the craft impacted the Indian Ocean. This would explain why it has not been visible in space, active or otherwise. If it existed in orbit, even briefly, that could have been enough to warrant the entry into the U.S. government’s catalogue of space objects.

Beyond SpaceX’s statement, though, all of the parties involved have continued to be tight-lipped about the launch. And we still don’t even know which arm of the U.S. government agency owns Zuma.

“I would have to refer you to SpaceX, who conducted the launch,” Dana White, the Pentagon’s chief spokesperson told reporters on Jan. 11, 2018, repeating the non-comment multiple times. Referring to the “the classified nature of all of this,” she said she would have “come back to you on that” with regards to whether there was an investigation into any possible mishap.

This is a particularly obtuse response to reasonable questions about what could be a multi-billion dollar accident, which could have serious ramifications, especially for SpaceX and its other U.S. government contracts. But the phrasing could also imply that Zuma’s owner exists outside of the Pentagon.

The U.S. military might not be able to comment on the situation, not because it doesn’t want to, but because it isn’t authorized to do so by whoever actually owns Zuma. It is typical U.S. government practice for one agency not to comment on another agency’s programs, classified or otherwise.

In addition, since it appears the matter of Zuma’s ownership is itself classified, the Pentagon would not be able to point reporters to the appropriate agency, because that would be disclosing classified information. If they cannot even identify the agency behind the project, which could be the Central Intelligence Agency, they would have little recourse but to point queries back to SpaceX or Northrop Grumman.

Another possible issue is that Northrop Grumman could itself be the main sponsor of the project, performing a technology demonstration or risk reduction effort as part of a public-private partnership with a U.S. government agency. As such, again, the Pentagon might again not be able to speak directly to the fate of the spacecraft per the terms of that agreement or simply because the contractor owns the spacecraft and intended to operate it on behalf of a government entity.

Why the Pentagon chose to single out SpaceX in this case rather than suggest journalists contact it and Northrop Grumman is less clear, though. Whatever the case, the Pentagon’s response has only muddied the waters regarding who is responsible for the spacecraft and its activities.

And this might point to a very different theory. There is a possibility that Zuma is actually working properly, but is otherwise masked from observers on the ground and their commercially available tracking capabilities.

That’s right, it’s possible that Zuma’s launch went exactly as planned, and that a new form of largely untrackable spacecraft has been put into orbit. This may sound far-fetched but it is anything but, especially when you take into account historical precedent.

The problem is in this day and age how do you get a very secretive, experimental stealth satellite into orbit without it being immediately tracked? There is no equally stealthy way of undertaking such an operation, at least not yet. As such, a cover story is needed so that the payload can begin its clandestine life in orbit without anyone having to admit that it’s up there at all.

The idea of stealth satellites is far from new. Concepts for producing hard to detect orbital spacecraft—on radar or via optical devices—date back to the 1960s, and we know that the federal government spent close to $10B on a pair of stealth imaging satellites that were launched in the 1990s. FAS.org has put together a compelling package of information about stealth satellite programs spanning decades that you can access here.

These highly classified orbital platforms, code named “MISTY,” were launched in 1990 and 1999, and could hide from radar and visual detection. In doing so they would presumably be able to make unpredictable photo runs over enemy positions and infrastructure and would be more survivable against ever-more capable anti-satellite weaponry. Standard satellites are easily trackable and follow along predictable orbits, with limited fuel onboard to change their orbital paths over their intended lifespan. As such, friend and enemy alike know when they will be overhead and adjust their operations accordingly. With this in mind, deploying satellites that don’t suffer from these limitations would be highly advantageous.

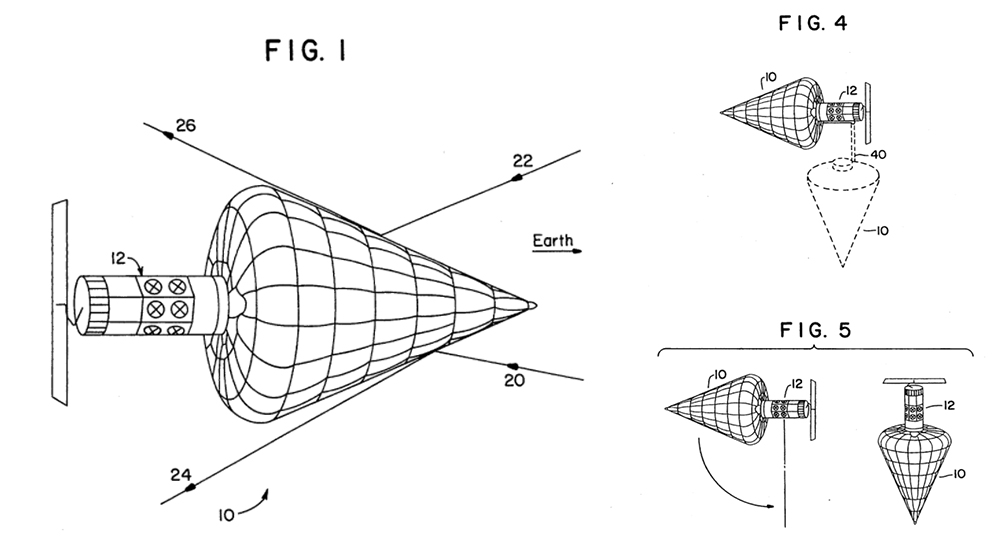

A number of concepts exist that would provide stealthy capabilities to orbital platforms. One of which includes cladding the craft with an array of dark and radar-absorbent faceted surfaces, which would act in a similar fashion as those used by early stealth aircraft. Others concepts include leveraging mesh screens that could baffle radar returns, and maybe most promising of all, the use of large inflatable structures that can hide a satellite from orbit until it needs to photograph something, after which it can go back to hiding behind its radar and visual barrier of sorts.

Both Teledyne and Bigelow Aerospace have patented various forms of this technology. Bigelow in particular seems especially suited for maturing this technology today as they have spent many years focusing on perfecting inflatable orbital structures. One is even deployed aboard the International Space Station.

We know that Zuma is some sort of very classified orbital spacecraft, and Northrop Grumman is one of the world’s top low-observable aerospace design firms. So it is very plausible that this craft is a new type of hard to detect, stealthy orbital system. Additionally, it may not be a reconnaissance satellite in the sense either, instead acting more like an adaptable vehicle that can execute dynamic maneuvers in orbit.

Now we get back to how one gets a nearly untraceable satellite into a defined orbit without giving away the fact that it indeed is nearly untraceable. Probably the best way of doing so would be to muddy the waters as to the payload’s fate following launch, while at the same time not officially lying to the public as to its actual status.

SpaceX says their rocket worked as advertised, and the federal government and the manufacturer won’t say anything else officially as to the condition of the payload, even though they could easily say that it failed to enter orbit without giving up any sort of information about its design, intended use, or even its intended orbit. But if Zuma actually made it to orbit, claiming officially that it didn’t would be a large-scale lie, and why go down that road when you don’t have to say anything officially at all?

In fact, if this was a highly sensitive payload that could not be easily tracked, even deploying a series of decoys via Northrop Grumman’s unique payload adapter would make a lot of sense. Those decoys would de-orbit as if the payload had re-entered the earth’s atmosphere. Sounds nuts? Grabbing for your tinfoil hat? Don’t put it on just yet because the fact is similar observations and a lot of similar confusion occurred following MISTY’s launch as well.

Space.com wrote the following in 2005:

“The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) initiated a number of stealth satellite programs during the 1980s. The NRO manages the nation’s spy satellite programs. The most notable of these was dubbed MISTY, a non-acronym but apparently a photo-reconnaissance satellite for snapping pictures.

“It was designed to be invisible to radar and optical tracking from the ground, but its photos were not as good as the big, non-stealthy reconnaissance satellites, like the Keyhole 11 and its successors. MISTY was launched from the space shuttle in 1990 in an unconventional way…it was rolled out over the side,” the source recounted.

Another stealthy satellite was launched in 1999 atop a Titan 4 rocket launched from California. Once again the amateur satellite trackers followed it, although after awhile they began to suspect that they were actually following a decoy and that the satellite itself was in a different orbit.”

“Misty 1 appeared to be a closed book until November 1990, when hobbyists in Scotland and France observed an unknown satellite in a similar inclination as Misty 1 but at a much higher altitude. Molczan’s computations showed that there was a good chance the mystery vehicle was Misty 1, meaning the orbital debris the Russians had tracked may have been decoys or debris purposefully generated to hide the intentions of the true satellite.

About a week after news articles announced what the hobbyists had seen, Misty 1 disappeared again, Molczan said.

As with Misty 1, shortly after Misty 2’s launch, nine pieces of debris were catalogued by the Air Force at or above the satellite’s initial orbit, Molczan said. Hobbyists tracked various objects, some for several years, but doubted that the primary satellite was among them. “No one has seen what might be the Misty 2 payload,” Molczan said.”

During the deployment of MISTY in 1990, there were also major claims that the satellite broke apart and that the Shuttle mission was a failure. In retrospect, it appears that some sort of decoys were released to confuse Russia space object trackers into thinking that it broke apart just prior to the satellite disappearing under some sort of cloak.

Not only do these historical accounts offer glimpses of potentially similar tactics, but fast forward to 2018 and imaging technology has made quantum leaps since the MISTY satellites were inserted into orbit. A modern stealth satellite likely wouldn’t be handicapped in imaging quality compared to its readily trackable cousins, and it could be smaller, allowing for greater capacity for stealthy technologies and maneuvering capabilities. In other words, the era of the stealth satellite may have finally arrived, one where very few if any tradeoffs between low observability and operational capabilities exist. If this is indeed the case, it couldn’t be any more timely.

By every account, space is a future battlefield. Anti-satellite technologies once only dreamed of are now possible, and America’s potential foes are actively developing and even deploying these systems. Considering that America realizes many strategic advantages via its high-reliance on space-based capabilities, any major rival, and even smaller ones, would take aim at those capabilities during the opening shots of a conflict. In essence, with every day that passes the Pentagon’s traditional space-based platforms are increasingly vulnerable to attack, with low earth orbit becoming an especially impermissible environment. You can read all about this dangerous new era of space warfare here.

Suffice it to say, working to develop a platform that can’t be easily tracked by enemy sensors would be a top priority of the Pentagon at this time. And this doesn’t just relate to imaging platforms that benefit from the element of surprise, but other types of satellites as well. Even communications satellites that could “selectively” shroud their position when their services aren’t in use, making them far more survivable than their “sitting duck” counterparts, would be a highly attractive capability for the Pentagon to acquire.

With all of this in mind, it’s really worth at least considering the possibility that Zuma actually did exactly what it was intended to do. With the help of just a sprinkling of non-official disinformation, it may have been able to start its mission under the best possible circumstances—disappearing into the darkness to go about its intended task from the shadows undetected.

What do you think happened to Zuma? Let us know in the comments below.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com