The Russian military’s top officer in charge of drone development has offered new details about apparent first of their kind mass drone attacks on its forces in Syria in an official briefing at the country’s Ministry of Defense. The presentation reiterated the Kremlin’s assertion that terrorists or rebels could not have conducted the operation without significant outside support, now implying a possible Ukrainian connection, but significant questions remain unanswered.

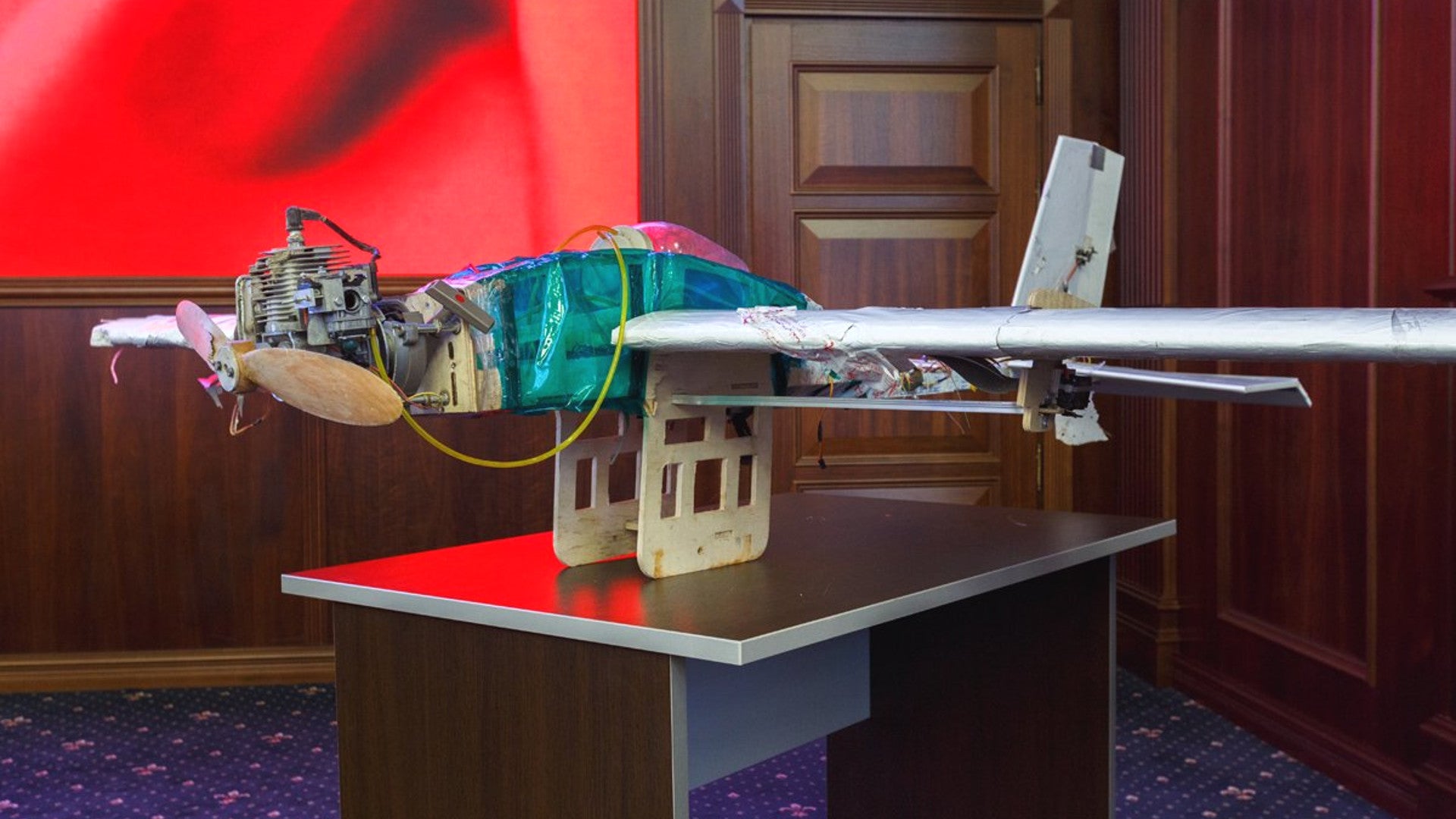

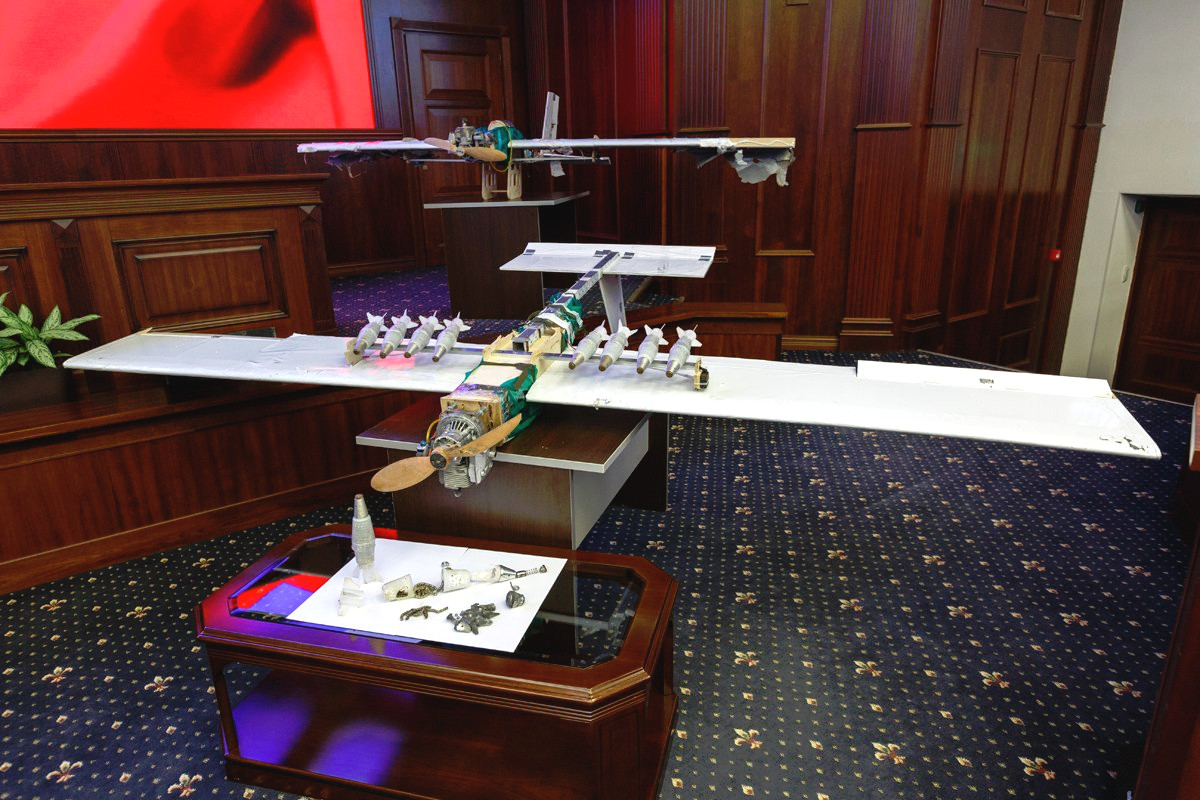

Speaking from the Russian Ministry of Defense’s briefing room, amid examples of the drones and their munitions that the country recovered after the attacks, Major General Alexander Novikov, head of the Russian General Staff’s Office for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Development, gave the most detailed and complete official description of the incident to date. He said that unspecified terrorists utilized a total of 13 improvised drones, each carrying 10 bomblets, sending 10 to Russia’s Khmeimim air base in Latakia governorate and the other three to its naval base in Tartus on the Mediterranean Sea. The munitions each had an explosive charge weighing nearly one pound, as well as strings of metal ball bearings or BBs glued together as pre-formed shrapnel, which would have made them most effective against individuals out in the open.

“Construction of these drones takes significant time period and special knowledge of aerodynamics and radioelectronics,” Novikov. “Assembly and use of these components in the joint system are a complicated engineer task demanding special training, scientific knowledge, and practical experience of producing these aircraft.”

Novikov said that Russian forces had been able to capture a number of the drones after electronic warfare systems at Khmeimim knocked them out of the sky. Somewhat confusingly, he later said that whoever had built the unmanned aircraft had included systems to specifically to defeat those countermeasures, though.

A video of Novikov’s full briefing is available online, with additional views of the captured drones and associated items and imagery, but the commentary is entirely in Russian.

Air defense radars aided in detecting the attacks and Pantsir-S1 short-range air defense systems destroyed some of the improvised unmanned aircraft, as well. He added that this was the first time Russian forces in Syria had come under such an attack, though rebels and terrorists have been employing such systems for years now in both that country and neighboring Iraq.

The general officer acknowledged that the individual components, such as the apparent lawnmower or moped motors, were available commercially. This is a point the U.S. military has been keen to stress in the aftermath of the attacks.

“We have seen this type of commercial UAV technology used to carry out missions by ISIS,” Pentagon spokesperson Major Adrian Rankin-Galloway told Russian state outlet Sputnik on Jan. 8, 2018. “Those devices and technologies can easily be obtained in the open market and that is cause for concern.”

However, Novikov insisted that militants would not have been able to conduct the necessary research and development and flight testing out of their workshops in Syria to make sure the improvised aircraft actually worked without significant assistance. “It is impossible to develop such drones in an improvised manner. They were developed and operated by experts with special skills acquired in countries that produce and apply systems with UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles],” he said, without naming where those individuals might be situated or where the militants might have received such training.

To support these assertions, Novikov focused heavily on the drones’ on-board GPS, which has become an important component of Russia’s allegation that outside actors, including one or more nation states, would have had to have been involved in the attacks at some level. The Major-General said the systems gave them military-grade precision when navigating to Khmeimim and releasing their bombs over the target area.

The “pre-programmed coordinates are more accurate than those in the Internet,” Novikov, challenging arguments that militants could have acquired the necessary data via open sources online. Though the briefing included maps of the pre-programmed flight routes, which the Russian Ministry of Defense said it had created using information it downloaded from the examples it captured, he did not provide any actual data to support his claims.

In his January 2018 briefing, Novikov also specifically appeared to suggest there might be a connection to Ukraine. He brought up the country when talking about the source of the explosive material inside the bombs the drones dropped on Khmeimim.

“The PETN [pentaerythritol tetranitrate] is produces [sic] by a number of countries, including Ukraine at the Shostkinsky Chemical Plant,” he explained. “This explosive material cannot be produced in an improvised manner or extracted from other munitions.”

Besides Syria and Russia, Ukraine was the only other country Novikov mentioned by name, according to the official transcript. He did not note that military forces around the world and commercial mining companies use PETN, which German scientists first developed in 1894, and that it is relatively easy to obtain.

The difficulty in spotting the explosive on typical airport x-ray machines has made it particularly popular with terrorists for more than a decade. “Shoe bomber” Richard Reid, “butt bomber” Abdullah Al Asiri, and “underwear bomber” Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, among many others, all employed or attempted to employ devices featuring PETN charges.

Russia and Ukraine have been at odds since the Kremlin seized the latter’s Crimea region in 2014 and subsequently began directly supporting separatists fighting the government in Kiev. The conflict has earned the Russian government international censure and economic sanctions from various countries, including the United States.

Ukraine is the third country Russia has indirectly implied might have aided the attacks in some fashion. On Jan. 9, 2018, an official statement from the Russian Ministry of Defense, as well as reports from state media outlets, strongly suggested that a U.S. Navy P-8A Poseidon patrol plane flying off the coast of Syria during the attack was somehow involved in the incident.

The implication was that the aircraft was feeding targeting information, such as the aforementioned GPS coordinates, or other information to the militants controlling the drones. These aircraft do have a robust electronic support measures suite that can collect information about various emitters, such as enemy radars, but additional electronic and signals intelligence systems have yet to become operational.

The idea that the United States is supporting ISIS, who may have been responsible, is a long-standing, but completely unfounded conspiracy theory. The U.S. government and its partners have armed groups opposed to Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad, though, most notably with TOW anti-tank missiles. Still, there is no actual evidence whatsoever the U.S. military had a role in the attack.

Then, on Jan. 10, 2018, the Russians indirectly pointed the finger at Turkey and rebel groups it backs in Northern Syria. The Turkish government is responsible for a so-called “de-escalation zone” in Idlib governorate, which is where the Kremlin says militants launched the drones. In 2017, Russia, Iran, and Turkey agreed to establish the ceasefire areas as part of a controversial plan that seemed aimed at challenging the influence of the United States, its allies, and its local Syrian partners, especially the Kurdish People’s Protection Units in the country.

According to The Washington Post, Russian officials sent a letter to their Turkish counterparts, not accusing them directly of involvement, but holding them responsible for the Khmeimim attack, blaming them for not being able to maintain the ceasefire in Idlib. Turkey in turn accused Russia and Iran of not keeping up their end of the bargain and demanded that they halt an offensive into the governorate, exposing potential fractures in the partnership.

The conspiratorial claims appear to be in response to these bold and unprecedented attacks coming so soon after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s victory tour of the Middle East in December 2017. This trip included a brief stopover at Khmeimim, where Putin declared total victory over terrorists in Syria.

As yet, the Kremlin has provided little firm evidence to support its assertions about foreign involvement. There is a growing body of evidence calling into question Russia’s insistence that militants could not have crafted the drones on their own, as well.

On Jan. 10, 2018, the Daily Beast reported that it had found similar drones for sale via the Telegram online messaging service, which militants in the Middle East and North Africa especially have increasingly used to conduct black market arms deals .The detailed investigation also turned up images of similar improvised unmanned aircraft and bomblets in Syria on Jan. 1 and 2, 2018. The munitions in particular are almost identical in design and construction to examples various research groups

have documented through open sources.

“From what I can see, this ‘drone’ was fabricated using wooden parts and tape,” Mike Blades, a drone industry analyst at the consulting firm Frost & Sullivan, told the Daily Beast. “Perhaps the servos and engine were purchased online, although it’s more likely been scavenged from a model airplane.”

On top of that, fighters with the Saray al-Areen militia, which is aligned with the Assad regime, said they had found one drones near Khmeimim on or about Jan. 1, 2018 and posted the video seen below, suggesting the unmanned aircraft had seen some action before the mass attack later in the month. On New Year’s Eve 2017 there was another attack on the air base, but Russian authorities said the militants used a mortar. The Kremlin also disputed reports that the incident had left a number of aircraft destroyed.

It remains unclear who has been responsible for this string of attacks. As yet, no group has officially claimed to have carried out the operations, despite their high profile nature and obvious propaganda potential.

“There’s a lot of fishy stuff going on in Idlib – agents running around, and groups working with groups they shouldn’t work with,” Aron Lund, an analyst at the Century Foundation, told The Washington Post earlier in January 2018. “It’s very, very murky.”

What is increasingly clear is that Khmeimim and Russia’s military and other interests in Syria are more vulnerable than many reports have previously suggested. The air base in Latakia province in particular appears to be under regular attack now.

It also seems safe to say that swarm drone attacks have arrived, albeit in a very primitive state, and are likely to become a major tool of both national militaries and terrorists and insurgents. It’s a danger that many, including us at The War Zone, have expressed concern about for years already.

In light of the mass attack in Syria, Russia has called for the creation of an international coalition to combat this emerging threat. Novikov said the Russian government was prepared to use all “appropriate measures” to eliminate the danger, without elaborating on whether this might involve an increase in military operations in Syria or elsewhere or sanctions or other actions against those it believed facilitated the attack.

“There is a real threat that terrorists can use drones for their attacks worldwide,” Novikov said near the end of his briefing. This particularly statement seems indisputable.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com