The Pentagon’s top watchdog has released a report that is highly critical of NATO-led, U.S.-supported efforts to improve and expand the Afghan Air Force, amid plans to triple that service’s size over the next five years. The review acknowledges that Afghanistan’s air arm has improved in some respects, but says significant gaps in training and logistical support remain, that coalition advisers are not adequately prepared for the tasks at hand, and that the international effort still lacks a coherent, overarching strategy.

The Department of Defense Inspector General, or DODIG, released the results of its assessment, which it had conducted between March and August 2017, on Jan. 4, 2018. The evaluators broke down their findings into six main conclusions, these being improving Afghan Air Force capabilities, an ill-defined advisory mission, private contractor support, broad training gaps, and how the Afghans made use of the Mi-17 Hip helicopter. All but one of these contained significant criticisms of the state of the Afghan force and the international advisory mission.

“TAAC‑Air’s efforts to train, advise, and assist the Afghan Air Force have resulted in notable accomplishments,” the report says in its executive summary, referring to the NATO-run Train, Advise, Assist Command-Air. “However, TAAC‑Air does not have a plan defining the terms of its mission statement to develop the Afghan Air Force into a ‘professional, capable, and sustainable’ force. TAAC‑Air cannot track the Afghan Air Force’s progress because they have not defined the intended end state and related metrics for determining the capabilities and capacities of the Afghan Air Force.”

This overall assessment that the U.S.-backed international mission does not have a way to determine if its efforts to improve the Afghan Air Force are working, or even central concept for how to implement its guiding principles, is shocking since the coalition has been working to develop the force for more than a decade. It is even more galling, given that, since at least 2016, the NATO-led security assistance mission in Afghanistan, known as the Resolute Support Mission, has been working to implement a much-touted Afghan Aviation Transition Plan (AATP).

This plan, which the Pentagon says will cost more than $800 million so far, aims to effectively triple the size of the Afghan Air Force. One of the AATP’s core goals is for the Afghans to field more A-29 Super Tucano light attack aircraft and MD 530F light attack helicopters, as well as add new AC-208 armed intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance planes and UH-60 Black Hawk choppers to their inventory.

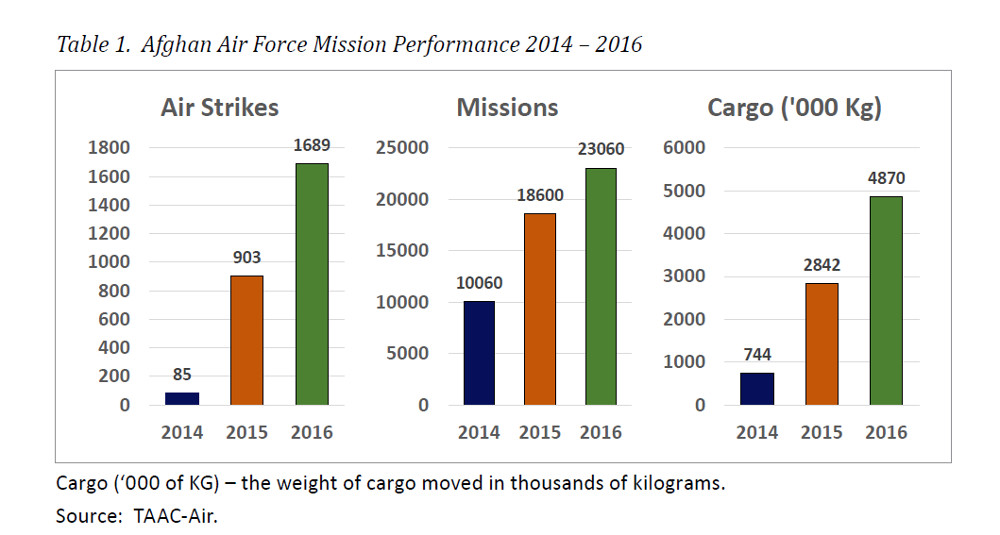

DODIG’s investigators did find some evidence that the Afghan Air Force was improving its abilities to operate its existing A-29s, fly at night with unspecified helicopter and fixed wing aircraft, and work directly with Afghan troops on the ground. In the first three months of 2017, the service had sent the Super Tucanos out on more than 10 times as many missions as they had in the last three months of 2016, according to the report. This was in line with a previous Pentagon report had noted that the Afghans had flown more sorties with the light attack planes in the second half of 2017 than they had in all of 2016.

At the same time, there were indications that Afghan pilots had taken the initiative to try and avoid potential civilian casualties. Between April and December 2016, A-29s had aborted nearly 20 percent of their attack runs due to concerns about innocent bystanders, friendly fire, or simply an inability to positively identify the target, according to the NATO Air Command-Afghanistan, or NAC-A.

There was no mention of the present inability of the Super Tucanos pilots to fly at night or that the aircraft still lack a long-promised precision guided munitions capability, which we at The War Zone were first to reveal. With precision weapons, the crews might have been able to follow through with more attacks, especially against moving targets or those where the enemy was dangerously close to friendly forces or civilians.

NATO advisers also highlighted the improving skills of Afghan Tactical Air Controllers (ATACs) and their increasing ability to call in air support independent of coalition forces. The Afghan military as a whole was steadily increasing the use of aerial support in day-to-day operations broadly, including for resupply and casualty evacuation. The Afghan Air Force had also stepped up coordination with teams of contractors operating Scan Eagle drones.

The report acknowledges that the latter coordination only occurs during the mission planning process, not while the Super Tucanos are in flight. Since these discussions occur over the phone or face-to-face, it might not involve the actual sharing of full motion video or other imagery the drones capture, either, something we at The War Zone have indicated could be the case in the past.

The A-29s are “a glimmer of hope to Afghan Air Force and the Afghan National Army,” head of NATO’s Train, Advise, Assist Command-South told the evaluators, a somewhat backhanded compliment to the country’s military as a whole. “A U.S. Intelligence advisor to the Afghan National Army 215th Corps supported this observation, saying that the A‑29s produce good results when they engage their targets,” the report noted.

But the rest of the review suggests that any improvements have likely come in spite of serious and long-standing structural problems on the part of both the coalition and the Afghan Air Force. TAAC-Air did not even have an approved plan of action to perform its mission until 2016, when the incoming commanding officer crafted a concept with four lines of effort touching on both the advisory unit’s strategic direction and what it actually envisioned as the Afghan Air Force’s end state.

This means that for at least a year, and possibly longer, the unit was working without any firm, overarching strategy or goalposts. In January 2015, NATO rebranded the NATO Air Training Command – Afghanistan, which had existed since 2008, as TAAC-Air.

DODIG redacted the actual four guiding principles from the version of the report it released publicly, so we don’t know what they are. This apparently puts us in the same position as some top advisers, at least as of 2017, though.

“Advisors’ responses revealed that TAAC-Air advisors do not share a consistent definition of the mission statement, nor a common way to achieve the mission end-state,” the report explained. “Finally, we asked the Commander of the [U.S. Air Force’s] 738th Air Expeditionary Advisor Group, a subordinate commander under TAAC-Air, if he was aware of the lines of effort. He replied that he had heard about them, but had not seen them.”

On top of apparently not agreeing on or even necessarily knowing what the coalition’s plan for the Afghan Air Force might be, DODIG found that advisers received no specific training or information about the service before arriving in country, though they did take courses on Afghan culture broadly. As such, they had to spend time during their temporary deployments, in which they were supposed to be aiding the Afghans in their day-to-day tasks, learning how their units operated, how they interacted with the coalition, and even the basic organizational and command structures of the country’s air force.

“Air advisors assigned to TAAC-Air reported they ‘…were less efficient and effective…’ until they achieved sufficient on-the-job training and completed the ‘…learning process…’ to acquire the requisite knowledge and skills,” the Pentagon investigators wrote. “This learning period delayed the development of the relationship between the advisors and their Afghan counterparts, thereby hindering the continued development of Afghan Air Force personnel.”

The impacts of this apparently haphazard approach were obvious in the criticisms the Pentagon watchdog leveled at the state of the Afghan Air Force. As the Pentagon routinely notes, and as we at The War Zone have reported on repeatedly, the Afghan military continues to lack an effective pipeline to train personnel for a host of key job descriptions, even after more than a decade of U.S.- and coalition-backed efforts to improve its capabilities.

Limited education, language barriers, and a lack of appropriate facilities, blended together with a host of socio-political factors – which some U.S. officials have dubbed “The Afghan Condition” – have long made it difficult for U.S. and other coalition forces to train and advise their Afghan counterparts. Training aviators and aircraft mechanics has been particularly difficult and Afghanistan still lacks the capacity to conduct the necessary training programs in country.

Sending Afghans to the United States and elsewhere to learn the necessary skills has proven costly and complicated. Trainees have abandoned their courses, possibly due to low morale, a desire not to return to the grueling fight, or just fears for their personal safety in Afghanistan. Some have outright applied for political asylum.

There’s no clear plan for how to improve the quality of training in Afghanistan, or the potential benefits of doing so, either. “The Chief of the Training and Education Division within the Security Assistance Office of Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan stated that the command does not know how much it costs to provide similar aviation-specific training within Afghanistan because no such aviation-specific training programs or institutions currently exist,” the report explained.

In addition, the Combined Security Transition Command-Afghanistan, the U.S. military’s top advisory element in the country, said there was no existing requirement at all for in-country training at present or in the future. As such, it couldn’t conduct an analysis of what it might cost to do so that would be in any way accurate.

The seemingly perpetually sluggish pace of training Afghan Air Force was particularly and unsurprisingly most apparent when it came to the service’s maintenance and logistics capacity, something we at The War Zone regularly highlight in our reporting about the Afghan Air Force. This issue warranted an entire section in the report by itself and indicated that the relying on private contractors to sustain Afghan aircraft, and how the coalition had implemented that support, was having a negative impact on the force as a whole.

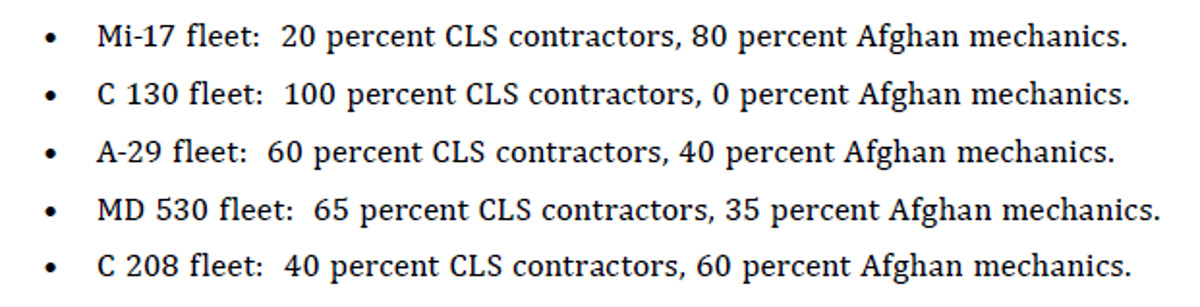

As of the end of 2017, private contractors were responsible for more than half of the total maintenance work on four of the six types of aircraft the Afghan Air Force operates. Those companies supply 100 percent of the support for Afghanistan’s C-130 Hercules transport planes and UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters.

NATO has and continues to award those contracts based on the immediate needs of the service, not an established long-term plan to turn those responsibilities over to the Afghans. This, in turn, “de-emphasized” the need for the Afghan Air Force to develop its own organic capabilities within a set timeframe. The wording of the C-130 maintenance contract actually bars the Afghans from working on their own aircraft, which makes it difficult for them to gain the necessary skills to take over in the future.

“Of all five CLS [contractor logistics support] contracts supporting Afghan Air Force airframes, only the contract covering the Mi-17 defined transition criteria or identified transition timelines,” the evaluators found. “As the exception, this contract directs the contractors to transition responsibility to the Afghans.”

This is something of a moot issue for this particular type, though. The Afghan Air Force already performs 80 percent of the maintenance on these helicopters, which both it and international coalition describe as the service’s “workhorse.” The other 20 percent is almost entirely heavy depot maintenance the Afghans can’t perform in country. On top of that, per the AATP, the United States and NATO are pushing for the retirement of this entire fleet and replacing them with UH-60s, a dubious plan we at The War Zone have already examined in depth multiple times.

A separate section described how the Afghan Air Force was just running those helicopters into the ground by giving regional Afghan Army Corps commanders direct control of small detachments to try and better meet heavy demand for air support. Those officials had no sense of the maintenance requirements, though, and were sending them out on missions even after it became clear they were in need of repairs, increasing the potential relatively minor problems could escalate to the point of requiring out-of-country depot maintenance.

Advisors told the DODIG investigators that they understood this was an unsustainable situation, but that they were unsure how else to get appropriate helicopter support to units in the field. Otherwise, they said, requests for support would have to go through a national-level command chain, which would slow down the pace of operations and put individual regions in direct competition with each other for aircraft.

All of these findings, of course, only underscore previous concerns that the Afghan Air Force simply lacks sufficient capacity to meet the country’s basic needs for responsive air power and that there’s no indication when this might change. The U.S. military has billed the AATP as a truly transformational endeavor that will finally put the service on the path toward a realistic, independent capability.

The DODIG report, however, calls the most basic underlying assumptions of that plan that into question. The Pentagon watchdog recommended that the TAAC-Air command finally publish a full strategic plan that includes the four lines of effort, make sure advisers got that information, and review the process by which it hires contractors to support the Afghan Air Force. It also said the U.S. military should better prepare advisory personnel for their mission and conduct a review of its requirements and procedures for training the Afghans.

The U.S. military concurred with every one of the Pentagon watchdog’s recommendations, which shows they are aware of the issues and the seriousness of the situation, too. At the same time, though, this hasn’t stopped them from initiating the purchases of new aircraft for the Afghans under the AATP or prompted a delay in the plan’s five-year schedule.

The U.S. military and NATO apparently developed the concept and initiated purchases of dozens of new aircraft, including all new types the Afghans have no experience with, while advisory personnel in the country were conducting their mission without any clear objectives. We at The War Zone have often questioned whether the Afghans would be able to readily absorb and sustain any significant number of additional airframes, especially new, more complex aircraft, such as the UH-60 Black Hawk, which are more maintenance intensive than existing types the country has. Based on the information available, there was already reason to believe this would actually hamper the Afghan Air Force’s operational capacity in the near term.

The review also underscored the reality that, unless the situation on the ground or U.S. government policy toward the conflict in Afghanistan changes dramatically, American forces in particular will continue to need to provide critical air support for Afghan troops as they struggle to contain the Taliban, ISIS, and other terrorists and insurgents. The United States is already quietly assuming something closer to a combat mission once again, increasingly deploying personnel on advise and assist missions and other joint operations in the field.

“The hard work, sacrifice and investment of our 39-member coalition is helping build the Afghan National Defense Security Forces and delivering on a coherent vision,” U.S. Air Force Brigadier General Lance Bunch, the director of the Resolute Support Mission’s future operations office, insisted to reporters on Dec. 12, 2017. “The momentum here has clearly changed, and the combat capability gap between the Afghan Defense Forces and the Taliban has never been greater.”

Based on the DODIG’s assessment, and the responses from commanders in Afghanistan, there still seems to be a long way to go in producing that coherent vision for the Afghan Air Force, even after more than a decade of coalition support.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com