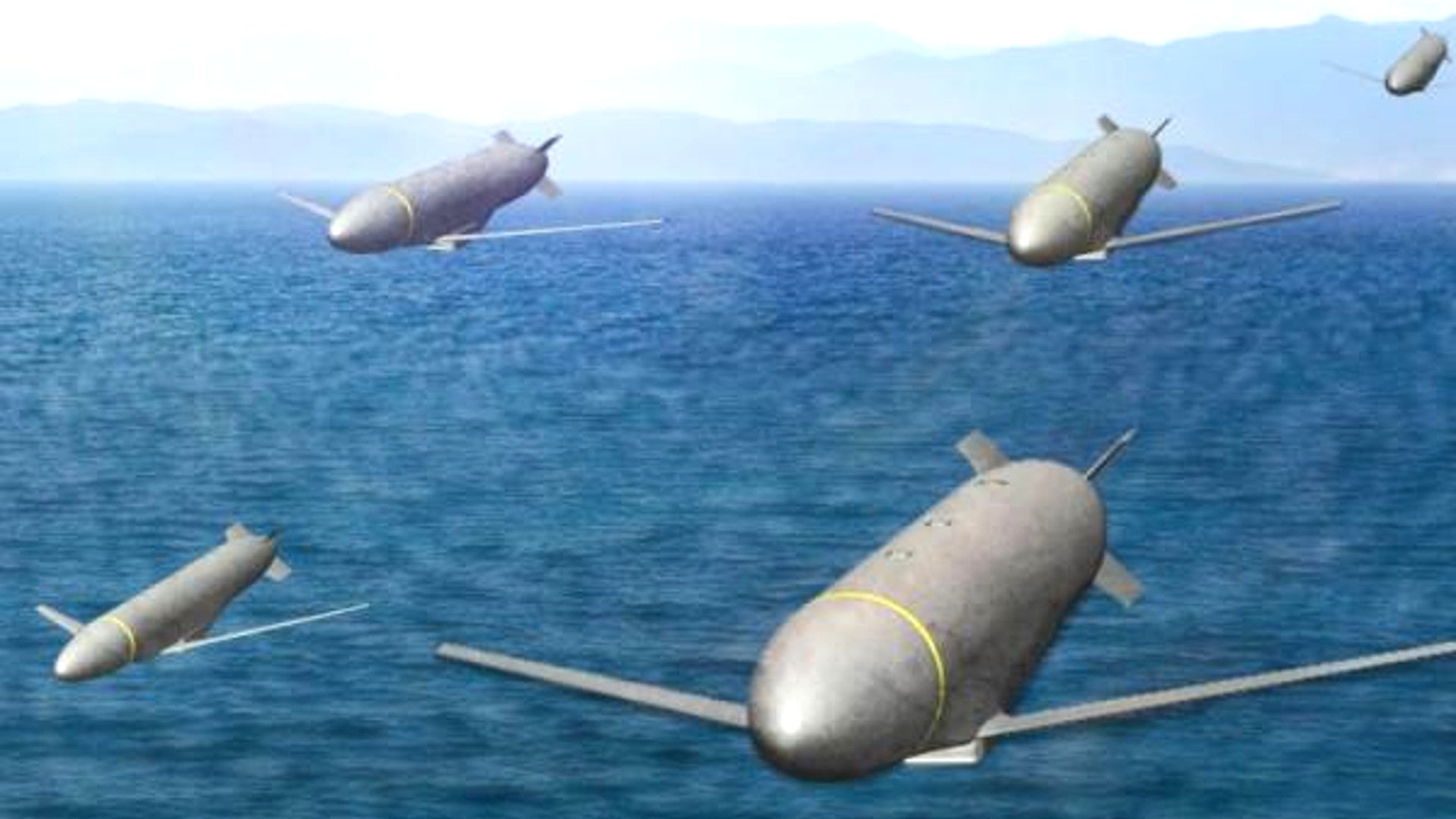

The U.S. Air Force has hired Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman to develop experimental low-cost cruise missiles that can act as a swarm in order to better navigate through or overwhelm enemy defense networks. As part of the project, nicknamed Gray Wolf, the service also wants a modular weapon that can readily accept updates and upgrades, as well as different payloads, ranging from conventional explosive warheads to electronic warfare packages.

On Dec. 18, 2017, the Pentagon announced the Air Force had awarded Lockheed Martin a $110 million contract for the Gray Wolf science and technology effort in its daily contract announcements. On Dec. 20, 2017, the notice said the service had made an identical deal with Northrop Grumman. The Air Force Research Laboratory’s (AFRL) Munitions Directorate at Eglin Air Force base is in charge of the project.

“Lockheed Martin’s concept for the Gray Wolf missile will be an affordable, counter-IAD [integrated air defense] missile that will operate efficiently in highly contested environments,” Hady Mourad, the director of the Advanced Missiles Program for Lockheed Martin Missiles and Fire Control, said in a press release the firm put out on Dec. 27, 2017. “Using the capabilities envisioned for later spirals, our system is being designed to maximize modularity, allowing our customer to incorporate advanced technologies such as more lethal warheads or more fuel-efficient engines, when those systems become available.”

According to Lockheed Martin, the contracts cover the first of four development phases, which will run through late 2019. The official contract announcements indicated that the Air Force expected the complete effort to wrap up in 2024. Northrop Grumman has not yet released its own official statement on its participation in the Gray Wolf program.

An F-16 test aircraft will be the first to demonstrate the Gray Wolf missiles. The goal is to make the weapons compatible with the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, the Air Force’s F-15E Strike Eagle, U.S. Navy and Marine Corps F/A-18s, as well as the B-1 Bone, B-2 Spirit, and B-52 bombers.

Otherwise, the Air Force has offered few in the way of specifics about the project. This isn’t particularly surprising for a science and technology effort, which will focus on exploring new concepts rather than producing a final production design.

In April 2017, Jack Blackhurst, who is both director of AFRL’s Plans and Programs Directorate and head of the laboratory’s Air Force Strategic Development Planning and Experimentation Office, offered important details in a briefing at the National Defense Industry Association’s annual Science and Engineering Technology Conference. According to the presentation, each of the spiral development phases will run for 18 months.

The basic technology goals break down into two separate lines of effort. The Air Force is interested in a weapon system that is low-cost and has a relatively short manufacturing time, even in small quantities. In addition, the missiles have to be capable of semi-autonomous, networked operation in order to defeat integrated air defense networks. This latter point is an increasingly important considering as the U.S. military increasingly has to take these defenses into consideration with regards to potential near-peer enemies, such as Russia or China, and smaller hostile powers, including Iran and North Korea.

Blackhurst’s briefing mentions cheaper guidance and sensor systems and “affordable and efficient” engines as specific areas of interest. A low-cost system with a sensor package could turn the cruise missiles into disposable intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance assets or loitering munitions that could wait for the best possible moment to attack.

The seeker heads should be able to target the enemy in multiple modes, which would make the weapons more flexible and able to hit their mark, even in the face of layered enemy defenses or just bad weather. In addition to just being able to try and intercept incoming cruise missiles, hostile air defense networks increasingly include electronic warfare capabilities that could prevent the launching aircraft or other friendly assets feeding course corrections to the weapons or otherwise disrupt their functionality and GPS-signal spoofing that might throw them off course.

In addition to the low-cost objective, an efficient engine could translate into more overall range for the weapon without increasing fuel load. Blackhurst stressed that this improved stand-off capability would be important to keep the launch platform safe from defense networks. Non-stealthy aircraft in particular are only becoming increasingly vulnerable to longer-range surface-to-air missiles with cuing from various radars and other sensors.

Launching swarms of the weapons together and developing a system that allows them to act in cooperation with each other, potentially exchanging information among themselves on potential threats and other hazards, would make the missiles themselves more survivable, too. Another of the Gray Wolf project’s goals is to have the entire group be able to find and strike targets on their own after launch, based on a set of pre-set parameters.

Taken together, a swarm of low-cost cruise missiles could make it cheaper and easier for the U.S. military to launch distributed attacks across a wide area. At the same time, it would force the enemy to expend significant additional resources to try and counter this particular threat, overwhelming their air defense networks or otherwise shifting their focus.

With a modular system, the Air Force could quickly add or reconfigure the missiles with electronic and cyber warfare capabilities, or just turn them into decoys mimicking the signatures of larger aircraft, all to further degrade the enemy’s ability to respond. This in turn could help defend other parts of the force package or pave the way for non-stealthy platforms to conduct follow-on strikes.

The trick will be combine all these features into a weapon that is more cost effective than existing types and thus not prohibitively expensive to use in a swarm attack. Most existing air-launched cruise missiles already feature network capabilities that could allow them to act in concert with each other, but which also have unit costs near or above $1 million a piece. Lockheed Martin has working hard just to get the cost of the Joint Air-to-Surface Stand-off Missile, or JASSM, an air-launched land-attack cruise missile already in U.S. Air Force service, down to approximately $800,000.

“Can the Gray Wolf missile be produced at very low unit costs and what are the associated design and manufacturing activities required to do so?” Air Force spokesperson Sharon Branick asked rhetorically in describing the Gray Wolf program to Inside Defense back in October 2016. “For example, are there innovative manufacturing concepts that would support low costs when built at low-rate quantities and without long-lead time lines? What capabilities would need to be traded off in order to maintain the low unit costs?”

This will be an increasingly important consideration when it comes to future advanced precision stand-off weaponry in general. Conflicts against small non-state actors have already threatened to exhaust U.S. military reserves of certain precision guided munitions. In a broader conflict against a larger near peer adversary, the Air Force and its sister services could easily burn through cruise missiles at a prodigious rate, especially if they employ them in swarms to defeat defense networks. Rapid, but low-cost designs and manufacturing techniques, such as those Gray Wolf will explore, will be essential to make sure there will still be stocks of these weapons after the initial phases of an operation and that replenishing the inventory won’t require diverting funds and resources from other projects.

One potential option is to have only a limited number of weapons in the entire group carry multi-mode sensors and then feed guidance information to the other missiles in the swarm. The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway has previously described this as a potentially lower-cost method of operating stealthy unmanned combat air vehicles, or UCAVs, writing in an earlier feature:

With UCAV swarms you do not have to equip every UCAV with the same expensive sensors and subsystems as you have to with manned fighters. Using adaptable open architecture and “plug and play” design philosophies, a group of UCAVs can be outfitted for a particular mission or mission set. By adapting a single airframe for various roles via a series of unique configurations, great cost savings can be realized without greatly hampering the effectiveness of the swarm as a whole.

In a single swarm “package” of UCAVs, you can have some airframes outfitted with advanced radars, some carrying networking, data-fusion and communications hardware, while others can carry highly sensitive electronic emissions sensing gear. Another set can carry bombs and missiles, while others can be outfitted with directed energy weapons (lasers) or advanced jamming equipment. Additionally, some can carry combinations of these capabilities. Because a package of UCAVs can act as a networked swarm and are constantly linked together via data link, each UCAV can share its sensor information with all the other UCAVs in its swarm and in real-time. When all this data is combined, a high-fidelity picture of the battlefield is rendered for the whole swarm to exploit. In other words, a UCAV that has no radar at all, can benefit from other UCAVs outfitted with such systems as if it were its own.

Even working as a small swarm of say six UCAVs, three could be optimized as simple munitions mules, two can operate as sensor craft, and one can be outfitted as an aerial tanker and jamming support platform. Although the munitions mules may not be equipped with a radar or other targeting and situational awareness sensors, they are virtually equipped with them as the swarm’s collecting brain can “see” a fused “picture” of all the UCAV’s sensor information combined.

Combining the weapons with a stealthy unmanned combat air vehicle, or UCAV, could also further extend their range into denied areas and improve the survivability of the missiles as they head toward their targets. AFRL is already experiment separately with low-cost “attritable” drones as potential “weapon trucks” working in concert with other manned and unmanned systems. Kratos’ XQ-58A Valkyrie is the test platform for that project.

Otherwise, much of the technology the Air Force is interested for the Gray Wolf missiles already exists publicly, at least to a certain degree, too. Lockheed Martin itself has touted many similar features in the design of its existing Long Range Anti-Ship Missile, or LRASM. This weapon is a derivative of the company’s JASSM cruise missile.

It’s no surprise that Mourad, the head of the company’s Advanced Missiles Program mentioned both of those weapons in the December 2017 press release. He also cited the firm’s Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) 227mm GPS-guided artillery rocket as an example of its experience with low-cost precision guided munitions. Lockheed Martin, along with Raytheon, is also competing to build the Air Force’s more traditional Long Range Stand-off (LRSO) weapon, which will be a new nuclear-capable cruise missile.

It is also possible that other companies may become involved in later development phases or that other, separate science and technology efforts or demonstrations might feed into the Gray Wolf project. In March 2017, AFRL had indicated it was looking to award “zero, one, or more contracts” for a then unnamed project matching subsequent descriptions of the notional Gray Wolf missile. At that time, it also indicated that there was $110 million in total available for contracts related to the program, an amount that appears to have increased given both the Pentagon contract announcements and Lockheed Martin’s press release.

Earlier in December 2017, Aviation Week reported that Boeing, General Atomics, and Kratos had all expressed an interest in the project, along with two other unknown contenders. Those could have been Aurora Flight Sciences, now a division of Boeing, or Dynetics, which is building the GBU-69/B Small Glide Munition for U.S. Special Operations Command. General Atomics and Dynetics are both on contract to develop swarming drones as part of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s Gremlins effort, as well.

Whatever happens it seems clear that systems such as Gray Wolf, which can carry out distributed attacks or other missions, will only become more important as integrated air defense capabilities continue to improve around the world.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com