The U.S. Air Force has released new details about its desired requirements for a possible program to re-engine its fleet of Boeing B-52H Stratofortress bombers. The service says it is hoping the upgrades could improve fuel efficiency by up to 40 percent, provide more on board electrical power, be hardened against nuclear explosions and cyber attacks, and otherwise keep the aircraft combat ready until at least 2050, at which point the youngest among them will have been in operation for nearly 90 years.

Between Dec. 12 and 13, 2017, the Air Force held a series of meetings with industry representatives at Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana, home of the 2nd Bomb Wing and its B-52s. The service released the briefing slides from those events on FedBizOpps, the U.S. government’s main contracting website, on Dec. 15, 2017, which FlightGlobal was first to report. Engine-makers Honeywell, General Electric, Pratt & Whitney, Rolls Royce, and Safran USA were all in attendance, as was Boeing and various other potential vendors, according to the briefing slides.

“This event does not indicate a promise by the Government to issue a request for proposal or a solicitation of any type,” the Air Force stressed up front. “Nothing discussed in this meeting authorizes you to work, start work, or bill for work.”

The need to re-engine the aircraft is steadily becoming inevitable at this point, though. One of the slides said that Air Force Global Strike Command, which oversees both the B-52s and the United States’ land-based, nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) force, expects the BUFFs to remain operational at least until 2050, and possibly beyond. The aircraft will be the primary launch platform for the up-coming Long Range Stand Off (LRSO) nuclear capable cruise missile. The bombers, which began to receive new equipment that allows them to carry precision guided munitions in their bomb bays in November 2017, will continue to fly conventional missions, well.

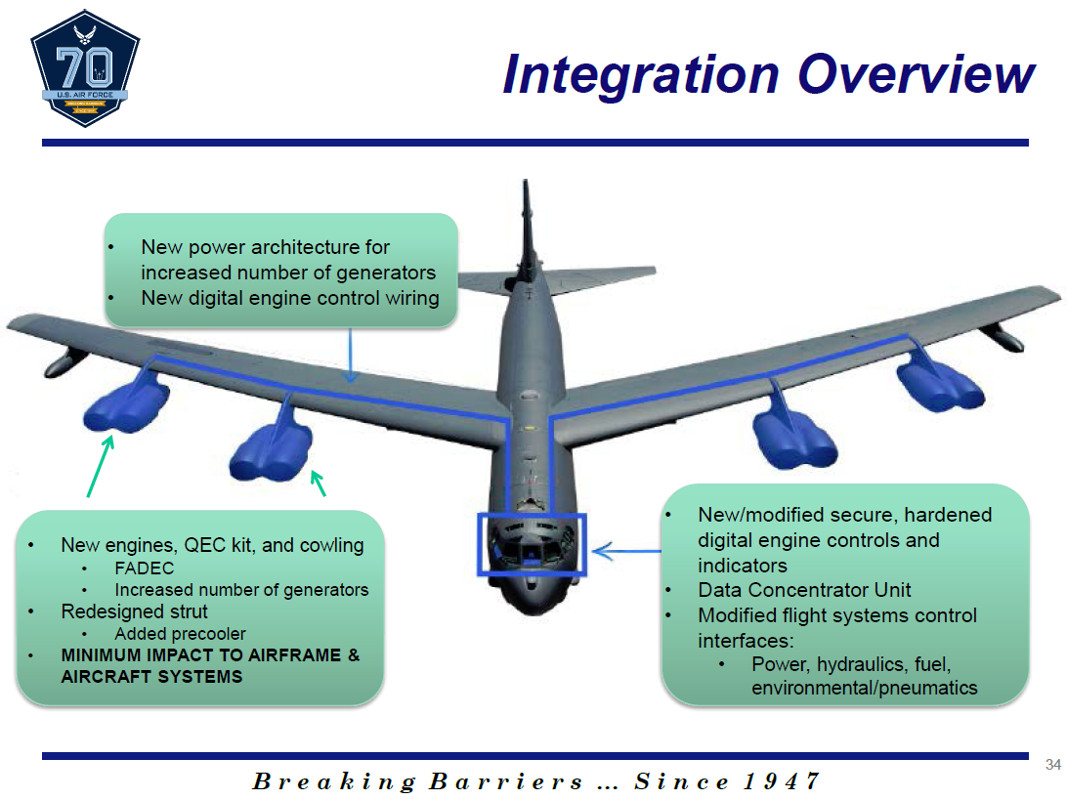

Re-engining the bombers will be essential if the service actually expects them to remain combat ready for nearly nine decades, and they clearly know it. The Air Force’s industry day confirmed that it is looking for a one-for-one replacement for each of the eight engines on its 76 B-52s – a full purchase order that would include at least more than 600 new engines, not counting spares, plus new nacelles and pods, electrical systems and other improvements.

The new commercial-off-the-shelf powerplants would need to be at least 20 percent more fuel efficient the existing TF33 turbofans. The last time the Air Force looked into re-engining the fleet in 2014 the minimum requirement was between 15 and 25 percent. But this 20 percent minimum increase in efficiency metric is just a threshold number, the service is hoping it might actually be able to find replacement engines that are up to 40 percent more fuel efficient.

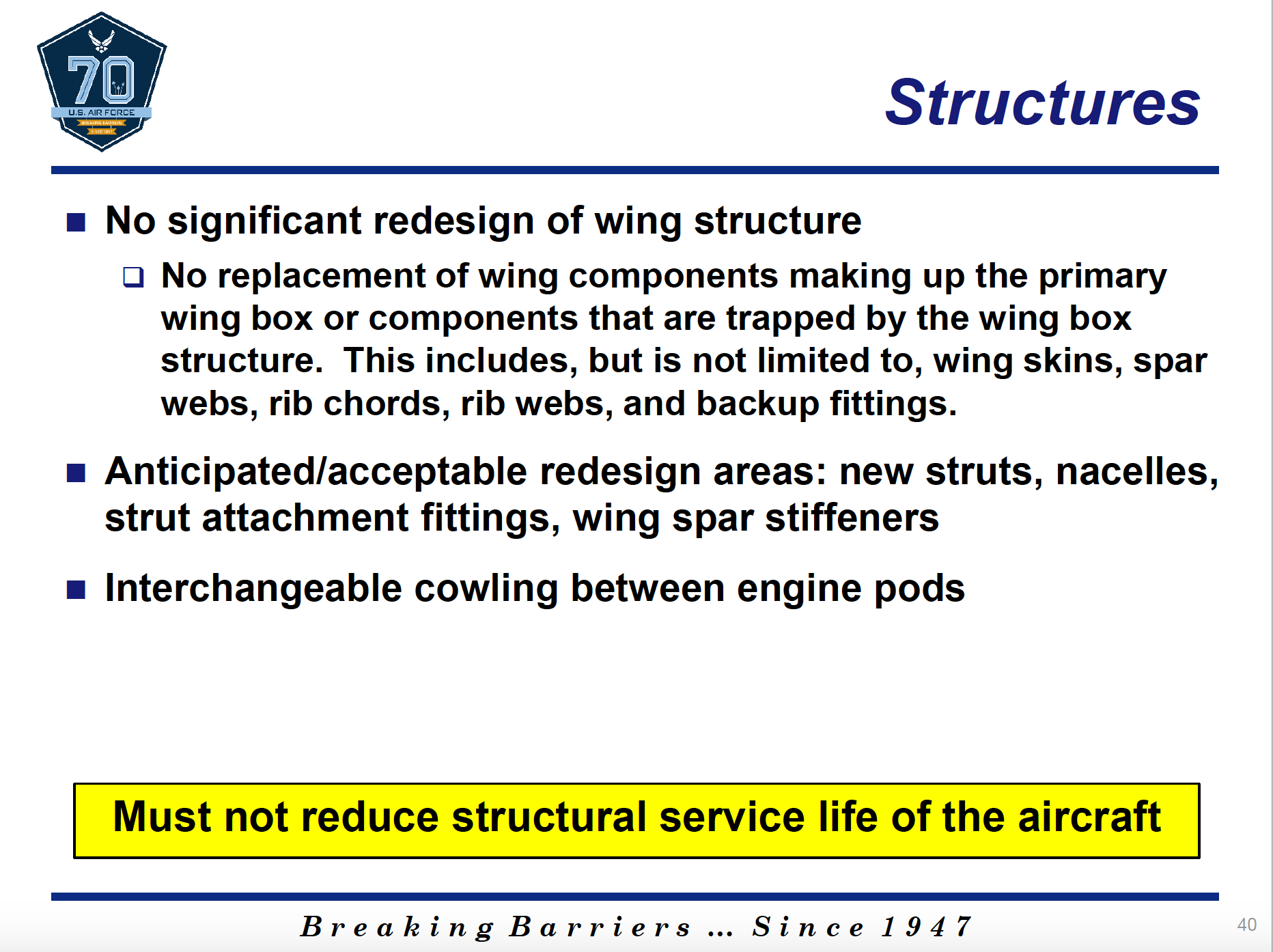

At the same time, the new engines can’t impact the aircraft’s flight performance, center of gravity, or limit its maximum takeoff weight or weapon carrying capacity. The Air Force does say it might be willing to consider changes to the aircraft’s structure that require changes in weapon release envelopes.

In line with the B-52���s nuclear mission, the engines and their associated hardware have to be hardened against electromagnetic pulses from nuclear weapons going off nearby. Any vendor that proposed a commercial engine with the ability to send out information wirelessly about its functionality for maintenance purposes would have to disable that feature and otherwise shield the system from cyber attacks.

However, the Air Force does want the engines to be able to record important functional data to help ground crews spot and identify problems. The 2014 plan called for a minimum of 15 to 25 years of service life on each engine before the need for a major depot-level overhaul and an overall sustainment plan laid out to nearly 2055. The briefing slides do not say whether or not these requirements have changed since then.

The eight engines should also be able to provide at least 400 kilovolt-amps (kVA) of on board power in total at a typical cruise speed, the same as a heavy duty portable commercial power generator, and potentially up to 500 kVA. The Air Force says the extra power is necessary to help support unspecified future upgrades, but lasers and standoff electronic warfare systems are likely growth capacities for a re-engined B-52, all of which require a lot of power.

Above all, the goal is to be able to implement this significant update without the need for dramatic changes to the wings, engine pods and pylons, and cowlings and nacelles. The new powerplants will need to seamlessly work with the existing fuel lines, as well as hydraulic and pneumatic systems.

The Air Force hopes whatever new engines it might buy won’t have a need for serious maintenance that requires ground crews to remove them from the aircraft entirely for at least 6,000 flight hours at a time on average, and up to 8,000 flight hours if possible. When the engines do come off, the service wants maintainers to be able to swap them out in four hours or less.

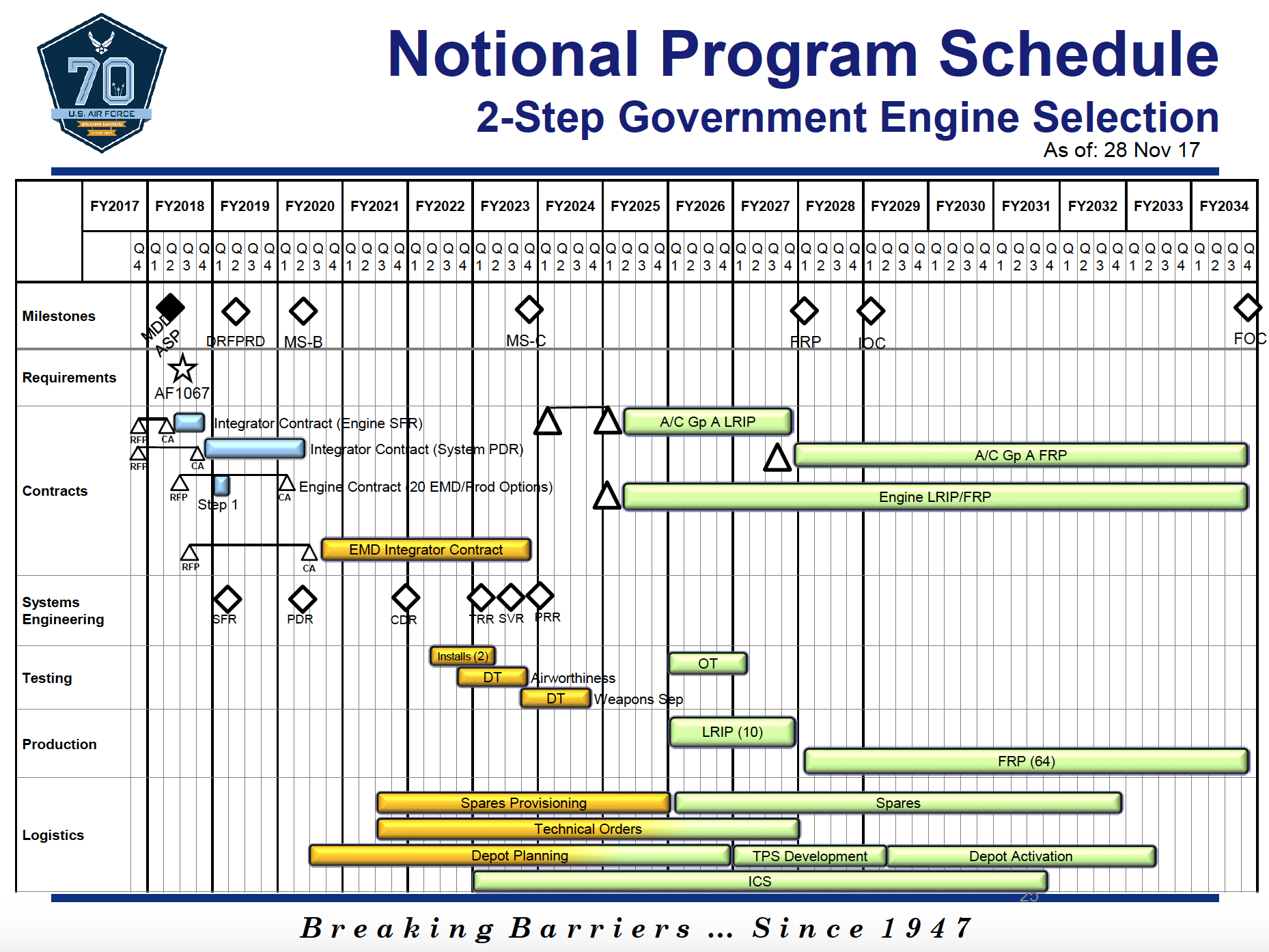

The biggest question that remains is how long it might take for the Air Force to get the re-engine program up and running. In its industry day briefings, the service said that there was a team already in place to manage the project and initial funds in the defense budget for the 2018 fiscal year that President Donald Trump signed into law on Dec. 12, 2017.

Unfortunately, Congress has yet to appropriate any actual money to go towards that budget and the U.S. government as a whole continues to move along on short-term funding measures known as “continuing resolutions.” At the same time, the Air Force itself has not settled on an acquisition plan, having described three potential courses of action that it could consider.

Two of these involve reviews of separate formal proposals for the necessary aircraft modifications and the engines themselves that are either simultaneous or split into a two-step process. The other option would be to let the contractor integrating the new engines on the B-52s pick the powerplants it deems best suited for the upgrade.

In its industry day presentation, the Air Force offered a detailed timeline of how the process might work under the two-phase plan. If it could get things moving in the 2018 fiscal year, the initial low-rate conversion process wouldn’t begin until 2025 and full-rate work would run through at least 2034.

This means the bulk of the B-52s could continue flying with their older engines for another decade at least. Each one of the existing TF33 turbofans, which have been out of production for decades, need a complete depot overhaul every 6,000 flight hours. This process costs the Air Force approximately $2 million every time.

As we at the War Zone

numerous times before, absent some form of public-private partnership, it could continue to be difficult for the Air Force to find the necessary funding for this new project as well as its other modernization priorities, including other updates for its two legs of the nuclear triad, such as the B-21 Raider stealth bomber, new IBCMs, and the LSRO program. That latest defense budget would provide ample funding these existing projects, but the Congressional Budget Office has warned that nuclear modernization plans alone could ultimately cost more than $1 trillion.

A public-private deal could get around this by offering to pay contractors primarily out of the cost savings from the new, more fuel efficient engines, potentially making the re-engine effort cost-neutral for the Air Force. If the suppliers can achieve the goal of a 40 increase in efficiency, this type of arrangement could be even more attractive. Agreeing to start work without a firm understanding off the ultimate benefits could still require a leap of faith for any vendors involved in the final project, though.

As noted, the Air Force will have to decide how it wants to proceed soon if it plans to get new engines onto the B-52s any time soon. In the meantime, the aircraft will continue to fly combat missions with the same engines they had when they entered service in the early 1960s.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com