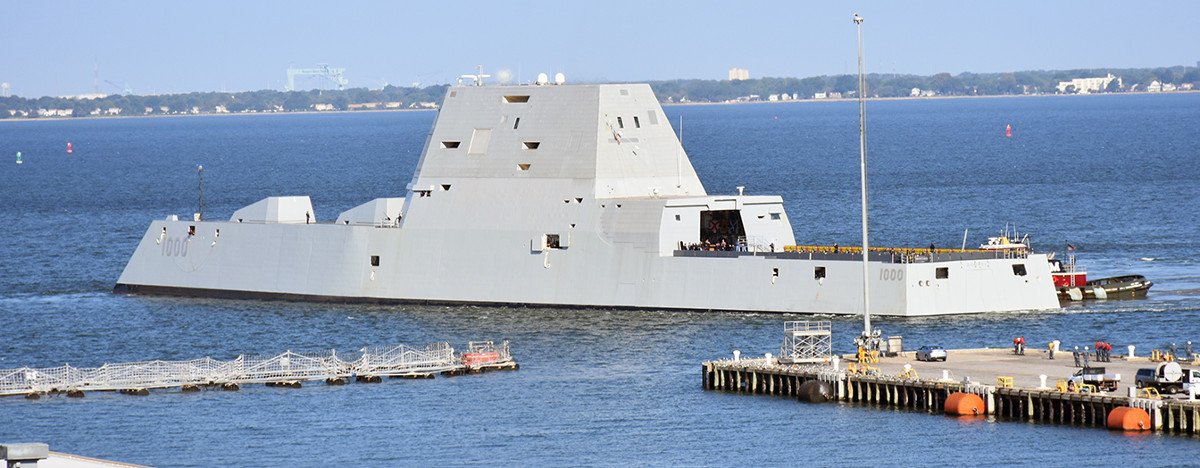

The future USS Michael Monsoor, set to become the U.S. Navy’s second stealthy Zumwalt-class destroyer, is underway for the first time for sea trials. The milestone comes as the service continues to reformulate the role of the ships, now saying they will be focused on attacking surface targets at sea, as well as on land, while the vessels’ future seems as uncertain as ever in the face of continuing budget shortfalls and personnel problems.

The second Zumwalt-class ship, also known as DDG-1001, sailed down the Kennebec River in Maine, on its way to the Altantic Ocean from Bath Iron Works (BIW) shipyards, giving journalists and others on the shoreline ample opportunity to grab a peek and take photos of one America’s most advanced warships. The Navy expects to commission the USS Michael Monsoor in 2018. BIW laid down the hull of the third and final ship in the class, the future USS Lyndon B. Johnson, in January 2017.

“Michael Monsoor (DDG-1001) is currently on Builders Trials, testing the hull, mechanical and engineering components of the ship,” Bath Iron Works said in a statement, according to the Portland Press Herald. “While all these systems are tested pier-side, there is no substitute for the real world testing taking place in the Gulf of Maine.”

Getting the second stealthy ship out to sea is an important achievement for both the Navy and BIW. The Zumwalt-class has been controversial to say the least and is the end result of a meandering set of often changing requirements and proposed ship concepts dating back to the 1990s.

The class was originally supposed to consist of 32 ships in total and has shrunk to a planned purchase of just three, with each one having a price tag of $4 billion. That’s not counting another $10 billion in research and development costs, either.

At the same time, though, the Navy has steadily hacked away at various requirements, stripping planned systems from the design, in no small part to try and control any further cost overruns and delays. Close-in protection, ballistic and air defense capabilities, and various other associated systems are no longer part of the base design, something The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway explained in detail in a past feature, leaving it with limited utility despite its size and cost.

In September 2016, he wrote:

“The various omissions in the Zumwalt’s capability have resulted in a ship that is focused on chucking cruise missiles and sending GPS guided cannon shells dozens of miles inland. But if the Navy wants a stealth Tomahawk chucker, guess what? They already have four of them with far more vertical launch cells than the DDG-1000 has. These are the converted Ohio class nuclear-powered guided missile submarines (SSGNs). In the coming years, Virginia class nuclear fast attack submarines with extended payload modules will take up this role as the four converted Ohio class SSGNs are retired.

“Minus its 155mm guns, has the stripped-down, anti-air mission-less Zumwalt become a far more vulnerable above-water guided missile submarine? A stealthy anti-submarine, special operations, and land attack arsenal ship? If so, why not build more submarines instead? They would be far more survivable and can stay on station much longer than the Zumwalt.”

To add insult to injury, in November 2016, the Navy admitted it had cancelled plans to buy the specialized and exorbitantly expensive Long-Range Land Attack Projectile (LRLAP), each of which would have cost some $800,000, for the Zumwalt’s main guns without an immediate replacement shell in the works. This effectively left one of the ship’s key weapons as dead weight. There ships will also receive various additional systems in the form of add-on packages attached to the deckhouse and elsewhere, which can only impact the ship’s finely tuned, complex, and expensive stealth shape in a negative manner.

The Portland Press Herald reported that, while she is officially in service, Zumwalt is still in the process of receiving unspecified weapons and critical mission systems at her homeport of San Diego. Now, struggling to find a job for the ships, the Navy says it wants to turn them effectively into floating arsenal ships full of stand-off weapons to strike at targets ashore and at sea.

On Dec. 4, 2017, U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Ron Boxall, the service’s director for surface warfare, told USNI News that officials were rethinking the Zumwalt-class’ requirements in light of experiences with the much maligned Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) and the new Guided Missile Frigate Replacement Program, or FFG(X). The stories definitely having some similarities, with the Navy struggling to improve the capabilities of the chronically under-performing LCS ships, before deciding to curtail its purchases and pursue a new design, which you can read about in more detail here.

“Let’s get this same type of team together and take DDG-1000, which has some of the most advanced capabilities of any ship we’ve ever produced, and at the same time look at some of the challenges we’ve had,” Boxall explained. “So looking at where we go with that [155mm] gun, how we can take advantage of what that ship is good at, and come up with a new set of requirements.”

“Obviously, a lot of those are classified, but the good news is that we’re going to look at focusing that ship more on offensive surface strike,” he continued. “And so this ship was already designed to do some of that mission, but we were focused on the very clear requirement we wrote for this ship in 1995, and the world has changed quite a bit since then. And so we’re modifying the missions and where we are with it.”

It’s not necessarily a bad idea, at least in principle. As we at The War Zone highlight routinely, developments in various, so-called “anti-access/area denial” systems, such as supersonic and hypersonic anti-ship missiles and progressively longer range integrated air defenses, pose an increasing threat to surface ships and any aircraft they might be carrying on board.

But more realistically, this is just the cheapest and easiest way to find an useful operational niche for the ships to fill. Focusing the stealth destroyers on this particular mission set is almost just a matter of filling the ships’ vertical launch system cells with a mix of land-attack and future over-the-horizon anti-ship cruise missiles, and maybe even finding usable ammunition of some sort for its main guns, but that isn’t really even a show stopper.

The Navy may not even have to split the Zumwalt’s 80 vertical launch system cells between two types of weapons as it proceeds with development of new versions of the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) that have an anti-ship capability. At present, the cells are partially dedicated to highly localized air defense, stuffed with quad-packed RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles. Those weapons could also offer a limited close-in defense against small swarming ships, as well.

The guns would present a different challenge. Even with the now cancelled LRLAP round, which featured a combination of GPS and inertial navigation as the guidance method, these weapons would have have been mainly useful against static targets, not mobile ships on the high seas. Using existing Army guided artillery rounds, such as Excalibur, would have run into the same problem, but the range of each shell would suffer badly compared to the LRLAP.

The Navy is working on a shell that can hit moving targets and do so in the increasingly likely event that an enemy is jamming GPS signals, but this ammunition is still in the research and development phase and it would require a forward deployed “third party{ asset to laser-designate the target. Work on an advanced electromagnetic railgun, which was one possible eventual replacement for the Zumwalt’s 155mm guns, but it is still similarly not in a state where an operational weapon is viable.

In high-threat scenarios, these newly refocused Zumwalts would be best suited to operating ahead of a larger force, making use of networked data links for stand-off targeting information, but still under the outer edge of an air defense umbrella provided by other assets, such as the Navy’s Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. They will undoubtedly leverage the Navy’s expanding Navy Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air, or NFIC-CA, for this surface strike role, something that it is almost certainly planning to do already.

This ambitious networking plan focuses on providing common data links between ships, aircraft, drones, and any other relevant asset to rapidly pass targeting information back and forth seamlessly. With the system in place, a Zumwalt could potentially launch cruise missiles at land or naval targets at maximum standoff range and in its maximum stealth mode, using data from various external sources, life stealth aircraft and satellites.

It could also pass control off of its launches cruise missiles to other assets operating nearer to the target area if necessary. With their own limited close-in defenses and degraded low observable design, the Zumwalts may still not be able to get close enough to take out more heavily defended targets ashore, though, including long-range radar sites.

But there’s a real question about whether or not giving the three-ship Zumwalt-class this operational mission makes practical sense or not. Making the stealth destroyers the service’s premier means of striking at enemy surface vessels, as well as land targets, in denied areas ahead of a major naval task for might give the ships something to do, but there would be few of them to go around in an actual contingency or during normal patrols. Also, this role is better served by submarines, both guided missile SSGN and fast attack SSN types, although the Zumwalts bring some networking and flexibility advantages to the fray. But are these small advantages enough to justify this limited role for the $22B class?

The fact that the service will stick the stealthy ships into Zumwalt Squadron One, rather than a unit that describes its function, such as a destroyer squadron, is another possible hint that it might still not know exactly what it wants to do with the ships.

On top of that, the costs to deploy and operate the unique ships could be significant separate from any other considerations. The Navy would have to weigh those costs against a number of other, more pressing priorities, including just making sure the surface force can meet its most basic operational obligations. A string of embarrassing and deadly accidents earlier 2017 has exposed serious, systemic issues that will take years to correct, even with appropriate funding, stable budgets, and clear vision.

In September 2017, Secretary of the Navy Richard Spencer and U.S. Navy Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson made a shocking public disclosure during a hearing before Senate Armed Services Committee that the service was only able to meet 40 percent of the total demand for surface warships at any one time. The next month, details emerged about a worrying maintenance backlog that was keeping attack submarines pierside for months on end – more than two years in the case of the Los Angeles-class USS Boise – in some cases just waiting for routine work to begin.

The sorry state of the Navy’s organic shipyards and subsequent increasing strain on private contractors only compounded these issues. In April 2016, the service had to inject $450 million into the Zumwalt program itself because of concerns about BIW’s performance and capacity.

Even if the Navy does deploy the Zumwalts primily in the surface strike capacity, it might not be for long as costs mount to operate the specialized stealth ships in this fairly limited role. It is still entirely possible that the Navy will see these challenges and ultimately decide to turn the Zumwalt’s into special projects and research and development vessels, just as it has done with its three Seawolf-class submarines. Or even worse they will turn into testing ships, with the small and highly unique fleet slowly cannibalizing itself to keep one hull operational. In the meantime this mission shift seems like an attempt to forestall this from happening, at least for the time being. Without the will to invest in the ships to make them what they were once intended to be, this at least gives them a notional purpose for the time being.

What’s most frustrating it that it’s impossible that the Navy wasn’t aware of these issues and this type of potential outcome as it rabidly stripped missions and capabilities from the the class during its development cycle, keeping the program roughly on track, but making it increasingly less relevant in the process. It was a conscious and avoidable decision as we have highlighted in great detail before, and now we will have to wait and see if these ships can win what will be a bloody fiscal battle to keep them in play.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com