Japan is reportedly looking into developing its own stand-off cruise missile that aircraft, warships, and land-based launchers all might be fire at hostile targets both on land and at sea. The decision comes amid growing tensions on the Korean Peninsula, as North Korea continues to develop its nuclear weapon and missile capabilities, and a long-running dispute with China over ownership of a remote island chain in the East China Sea.

On Nov. 20, 2017, The Yomiuri Shimbun reported that the Japanese Ministry of Defense would research adding a land-attack capability to an unspecified existing anti-ship missile development programs. Research and development would start some time during the 2018 fiscal year, which began on Oct. 1, 2017, but the newspaper did not give a timeline for when the missile might be ready for tests or enter service.

Yomiuri’s report did not offer any other details about the weapon’s estimated range or capabilities, or whether it would be a clean sheet design or a derivative of a type already in development, but described it as a “Japanese Tomahawk” in reference to the American-made Tomhawk Land Attack Missile, or TLAM. The latest Block IV TLAMs have a range of approximately 1,000 miles and the manufacturer, Raytheon, is working with the U.S. Navy on an anti-ship subvariant.

The existing Tomahawks can only attack static targets, but can receive instructions mid-flight to strike a different position. The Block IV missiles can loiter over a specific area, as well, and provide a limited view of the battlefield with their on board camera, before dropping onto the enemy. The future Maritime Strike Tomahawk version will have the ability to attack moving ships.

A Japanese missile with similar range and a combination of these features would give the Japan Self-Defense Forces an important boost in overall capability. In May 2017, there were reports that the country might be interested in just buying Tomahawk missiles from the United States to quickly field this type of weapon.

However, a Tomahawk-like weapon would be far too large for any multi-role combat jet, such as Japan’s F-2, to carry. At present, the only stand-off weapons the F-2s can carry are two types of anti-ship missiles, the ASM-1 and ASM-2. The longer range ASM-2 can only engage targets approximately 100 miles away. The land-based Type 88 anti-ship missile and the ship-launched Type 90 version both have similar ranges.

The still-in-development supersonic XASM-3, which will replace the existing air-launched weapons, will still have a maximum range of less than 125 miles. That being said, a new, multi-platform missile that could reach targets even four or five as far away, such as Lockheed Martin’s Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile-Extended Range (JASSM-ER), would give the country’s aircraft, warships, and ground forces more flexibility to respond quickly and accurately to regional crises.

This class of weapon has significantly longer range over Japan’s existing missiles and would help any launch platform – aircraft, ships, or land-based launchers – avoid the threat of enemy defenses and counter-attacks. Another option could be to use an air-launched drone, similar to the Kratos XQ-222, to carry existing weapons closer to the target.

Since the late 1990s, Japan’s Technical Research and Development Institute (TRDI), analogous to the U.S. military’s Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA), has been experimenting with a small, turbofan-powered, multi-purpose drone from Fuji, commonly known by its Japanese acronym TACOM. Though it has been more commonly seen with a sensor package for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions, it could possibly serve as the a basis for semi-reusable unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV). It might even be a useful starting place for a more conventional cruise missile and the Japanese have already tested TACOM with an F-15J fighter jet acting as the launch platform.

With a high speed or low-observable features, and networked with near-real time intelligence from forward-deployed radars and other sensor nodes, as well as possessing its own decision making ability and passive sensors, the final missile or drone design itself could be more survivable and better able to respond to fleeting, time sensitive targets.

This latter point is particularly important with regards to the steadily escalating tensions on the Korean Peninsula. In 2017 alone, North Korea has successfully test fired a number of new road-mobile

ballistic missiles that can hit Japan and may be able to carry a miniaturized thermonuclear warhead or chemical weapons.

In August 2017, Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga told reporters that the country would respond firmly after the North Koreans fired a ballistic missile over the country’s home island of Hokkaido. In September 2017, North Korea responded with a threat to nuke Japan and sink it into the ocean, saying it “is no longer needed to exist near us,” and fired another missile across the country.

Japan has since taken part in a number of shows of force with U.S. military forces in the region. Its F-2 fighter jets have flown with U.S. Marine F-35B stealth fighters and U.S. Air Force B-1 bombers. More recently, earlier in November 2017, the Japanese helicopter carrier Ise sortied out to join a rare and massive U.S. Navy exercise involving three full carrier strike groups.

But with its present capabilities, if a conflict with North Korea were to break out, Japan would have to rely almost entirely on its allies for any actual strikes, especially before any initial strikes neutralized most of the country’s aging, but dense air defense network. With a cruise missile of their own, the Japan Self-Defense Forces would be better positioned to directly contribute to any such campaign or conduct strikes independently in the face of an imminent threat, most notably by hitting missiles while they are in their vulnerable launch position.

The Japanese could integrate any new long range cruise missile with the Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense architecture they are also planning to buy or look to buy Tomahawks for those sites as a supplement to its own development. A missile with a 500 to 600 mile range would still put these land-based launchers well within striking distance of targets in North Korea if they were situated in the country’s home islands and the weapons would offer a standing and visible deterrent. Any missile that could fit into the Aegis Ashore would also work with the Mk 41 vertical launch systems, found on many of Japan’s destroyers, too.

At present, the country’s post-World War II constitution still limits how pro-active the Japanese government can be militarily, but that could be changing, as well. In 2014, Japan said Article 9 of the constitution, which prohibits offensive military action, would not apply to “collective self-defense,” or coming to the aid of an ally under attack.

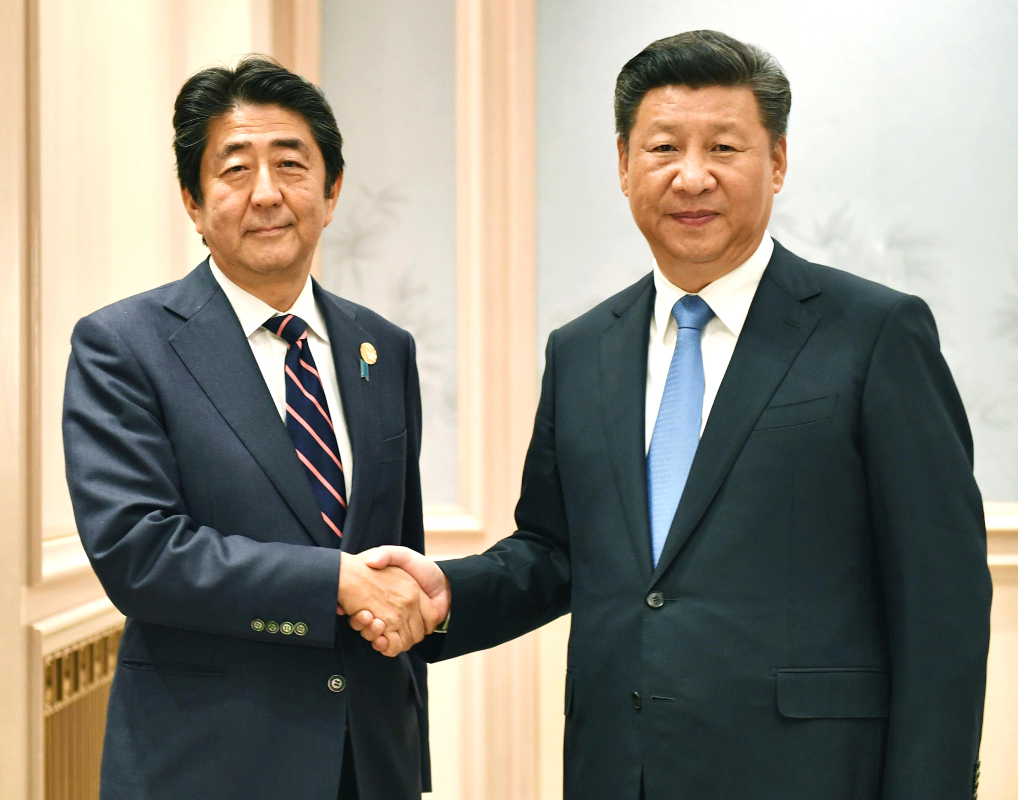

In May 2017, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called for an extensive review and revision of the article no later than 2020, ostensibly to make sure the law accurately reflect the state of affairs in East Asia and the world as a whole. China and South Korea, both of which suffered greatly under Japanese occupation during World War II, have long opposed any attempt by Japan to re-militarize.

But it appears that Japan increasingly feels it has little choice, not just because of North Korea, but because of increasing Chinese provocations in the East China Sea. Authorities in Toyko and Beijing have long disputed the ownership of a chain of uninhabited islands that the Japanese call Senkaku and the Chinese refer to as Diaoyu.

In 2013, China announced the creation of a so-called “Air Defense Identification Zone” over the area, demanding that military and civilian aircraft passing through inform Chinese authorities of their flight plan and follow any instructions. The United States, Japan, and a number of other Asian countries have largely rejected China’s authority to set these rules or have said they will ignore them.

Unfortunately, the islands are closer to mainland China than to Japan’s home islands. Japanese authorities have long been concerned that Chinese troops could rush into the area and land on the islands in an attempt to physically seize control before the country’s own military would have a chance to challenge the move. China has been steadily expanding their expeditionary naval capabilities, including, but not limited to new aircraft carriers, amphibious ships, and a number of large Zubr-class hovercrafts.

The Zubrs could make it from the Chinese mainland to the Senkakus in just four hours without any support. The Chinese could decide to preposition them closer to the area ahead of an actual operation, though, and they have already conducted tests with one of the hovercrafts operating from the Donghaidao, a semi-submersible logistics vessel that could potentially function as a small sea base akin to the U.S. Navy’s much larger Mobile Landing Platform ships.

As such, the new Japanese cruise missiles could provide an anti-access/area denial type capability, possibly forcing the Chinese to reconsider any of these military options to assert authority over the islands. Coupled with the aforementioned forward-deployed sensors nodes or aerial patrols, the Japan Self-Defense Forces would be able to not only better monitor China’s activities in the East China Sea, but present a deterrent to them, as well.

In 2016, Japan positioned a mobile search radar on the nearby inhabited island of Yonaguni to improve its situational awareness in the area. There were also reports that year that the country was looking into developing a ballistic missile system to defend its territorial claims, though this could have been an error of some sort and instead been a reference to a desire for a stand-off cruise missile.

Tit-for-tat air and naval patrols and shows of force between Japan and China both in and around the Senkaku islands and in East Asia more broadly have become increasingly routine. Just between April and June 2016, Japanese jets intercepted nearly 200 Chinese military aircraft in and around the island chain.

In March 2017, the Japanese announced they would send the helicopter carrier Izumo on a three month patrol in the South China Sea, where China also claims large swaths of territory. Then, in July 2017, the Tianlangxing, a Chinese Type 815G spy ship, made a provocative trip through Tsugaru Strait, which runs between Japan’s home islands of Honshu and Hokkaido.

Earlier in November 2017, Chinese H-6K bombers, as well as various electronic warfare and signals intelligence aircraft, made flights over the Miyako Strait, which separates Okinawa from the Miyako islands in the East China Sea. These Japanese-controlled islands are less than 150 miles southeast of the Senkakus. Japanese F-2s scrambled to intercept and monitor the Chinese aircraft.

And with regards to these increasing security concerns both on the Korean Peninsula and in the East China Sea, a long-range cruise missile would offer a relatively cheap and simple means of giving the Japan Self-Defense Forces more flexibility. The basic technological requirements of such a system are well established and it is likely that the Japanese could still secure the aid of the United States in developing a relatively advanced indigenous design.

“The prime minister of Japan is going to be purchasing massive amounts of military equipment, as he should,” U.S. President Donald Trump said during a shared press conference with Prime Minister Abe in Tokyo during a state visit earlier in November 2017. “It’s a lot of jobs for us and a lot of safety for Japan.”

The Japanese are already heavily involved in the development of Raytheon’s SM-3 ballistic missile interceptor. It is possible the company might just offer to co-develop an actual Japan-specific Tomahawk derivative with a domestic defense contractor to meets the country’s final, particular requirements.

It seems clear, though, that one way or another, various elements of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces will have a new and pronounced stand-off capability sooner rather than later.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com