After meetings with U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff U.S. Marine Corps General Joseph Dunford, the South Korean government has announced its intention to buy more “high tech capabilities” from the United States for its military, continue its own long-range missile development programs, and expand strategic cooperation with the U.S. military to improve the country’s defenses against North Korea.

The statements came amid persisting heightened tensions on the Korean Peninsula and it’s unclear as ever whether these new announcements are more likely to restrain the Hermit Kingdom or provoke premier Kim Jong-un into making new threats or taking more provocative action.

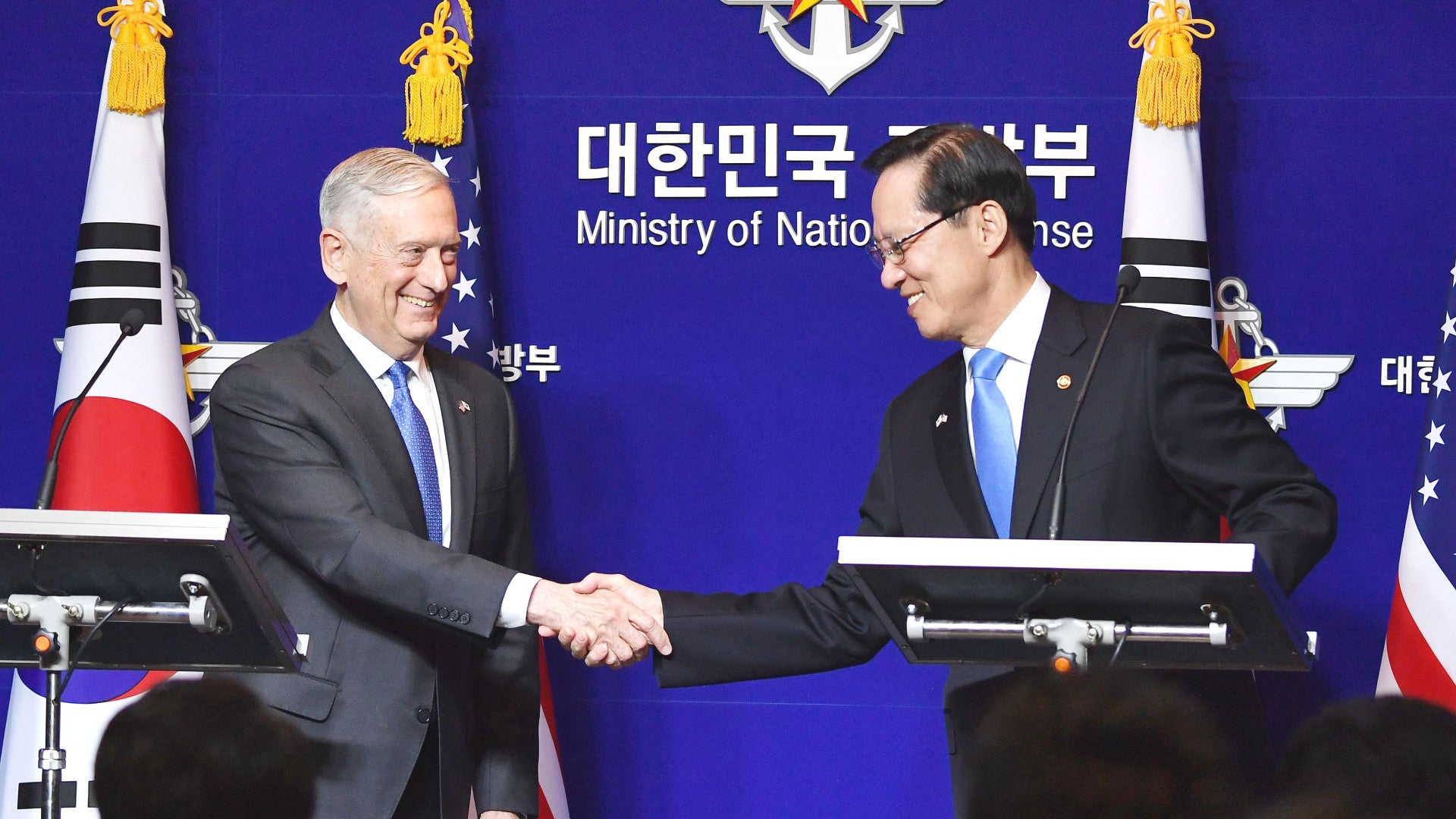

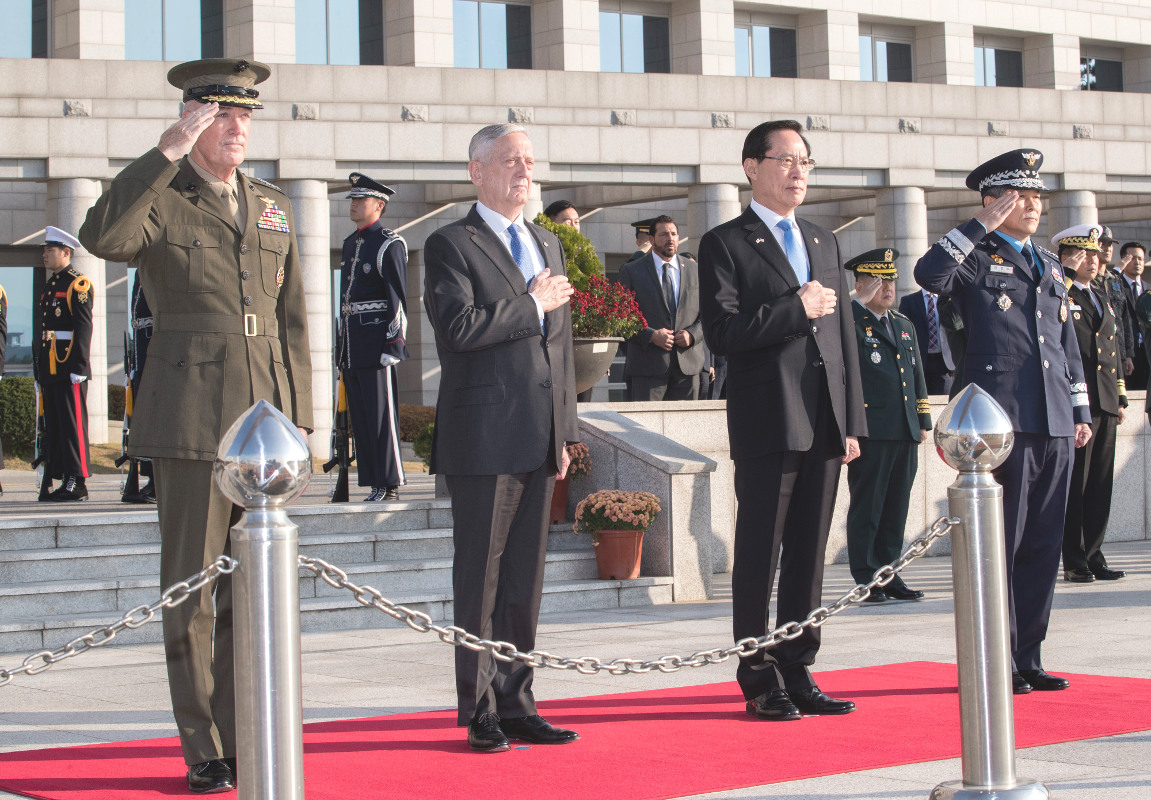

South Korean Defense Minister Song Young-moo revealed these defense priorities at a shared press conference with Secretary Mattis in the country’s capital Seoul on Oct. 27, 2017. Mattis and Dunford had arrived in South Korea on Oct. 26, 2017 for a series of high profile meetings with their counterparts in the country, also known as the Republic of Korea (ROK) regarding how to approach the ongoing crisis on the Korean Peninsula over North Korea’s provocative ballistic missile and nuclear weapons tests and subsequent threats.

Nuclear deterrence

“First and foremost, the ROK and U.S. government condemn in the strongest terms the reckless provocation by North Korea, including the six nuclear tests and the multiple ballistic missile launches,” Song said through a translator. “We have agreed to continue supporting the diplomatic efforts by the Korean and U.S. governments to denuclearize North Korea and back up our government’s efforts with firm ROK-U.S. combined defense posture.”

The bulk of what Song discussed in the rest of the press briefing is necessarily not new. On Sept. 4, 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump and South Korean President Moon Jae-in spoke on the phone following North Korea’s sixth nuclear test, the detonation of a thermonuclear or hydrogen bomb.

According to an official White House readout of the chat, the two leaders discussed increasing their shared military capabilities, renegotiating the limits on South Korea’s missile development work, and “many billions of dollars’ worth” of future arms sales. But Song’s remarks did add new and important context.

Most notably, the top South Korean defense official said that discussions about the deployment of unspecified U.S. military “strategic assets” to the country and the Pacific region as a whole included examining “the implementation of extended deterrents and commitments.” As it stands now, the United States already includes South Korea in its so-called “extended deterrence” posture, which places it under the protective umbrella of America’s nuclear arsenal.

With North Korea rapidly expanding its own nuclear weapons capability and the necessary delivery systems, it’s understandable that South Korea would want to review the situation and make sure the threat of a massive American retaliation is as credible as ever. In addition, given the close proximities involved, it could be difficult, if not impossible for the United States to launch a nuclear response before North Korean missiles hit their targets in the South. Earlier in October 2017, the U.S. Air Force walked back a report that it was exploring the possibility of putting nuclear-armed bombers back on 24/7 alert, in part because of growing concerns over the situation on the Korean Peninsula.

As such, authorities in Seoul could easily be interested in discussing just what options might exist for a preemptive or preventative strike and when it might be politically and legally possible to put those plans into action. The United States, importantly, does not have a “no first use” policy regarding the use of nuclear weapons, leaving open the possibility of responding with these devastating weapons in response to a conventional crisis. We at The War Zone have already written a detailed look at how the U.S. military might go about launching a nuclear strike, thanks to documents obtained via the Freedom of Information Act, which you can find here.

However, both the United States and South Korea have denied

or deflected that there are any serious discussions about the U.S. military to redeploying nuclear weapons to South Korea itself, at least on a permanent basis. It is possible that rotating “strategic assets” could include actual weapons on bombers or changes to the top secret patrol patterns of ballistic missile submarines.

American officials ordered the last remaining stockpiles of nuclear weapons removed from US bases on the Peninsula in 1991. Defense Minister Song did say reintroducing the weapons was something worth looking at in Sept. 2017 and Mattis confirmed they had talked about it later that month.

Strategic assets

However, there have been reports in South Korea that the U.S. military is considering deploying B-2 Spirit stealth bombers and F-22 Raptor stealth fighters to South Korea on a rotating basis and a B-2 made an apparent flight to and from Guam while Mattis and Dunford met with their counterparts in Seoul. The U.S. Air Force has also announced plans to begin rotational deployments of the F-35A Joint Strike Fighter to Japan beginning in November 2017.

These would be the kind of aircraft that would most likely fly the opening missions of any actual strike against North Korea. And unlike the B-1 Bone bombers that have been a key feature in shows of force in the region, the B-2 is capable of carrying nuclear weapons.

Earlier in October 2017, the U.S. Navy revealed that it would have three aircraft carrier strike groups in the Western Pacific for the first time since 2011. Aircraft carriers have long been one of, if not the most eminently visible display of American military power.

The Pentagon downplayed the latest development, saying U.S. officials had made the decision to have the carriers in the region months in advance, but the message seems unmistakable. Along with the long-range attack capabilities of their air wing, they could help deliver special operations forces for “decapaitation strikes” against the North Korean regime, while their escort ships – which include Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, Ticonderoga-class cruisers, and Los Angeles-class attack submarines – might launch their own stand-off strikes with Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles. None of the ships have the capacity to launch a nuclear attack, though there is the possibility the U.S. Navy may add this capability to its future F-35C Joint Strike Fighters.

“This was a unique opportunity for – to show that the U.S., the only power in the world that can demonstrate that kind of presence, and a unique, you know, opportunity for them to be together,” Joint Staff Director U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant General Kenneth McKenzie said during a press conference on Oct. 26, 2017. “It does demonstrate a unique and powerful capability that has a very significant assurance effect on our allies in the Western Pacific,” he noted later in the briefing.

Earlier in 2017, the Navy put the USS Carl Vinson and her strike group off the coast of the Korean Peninsula. On Oct. 21, 2017, the USS Ronald Reagan

made a visit to the South Korean port city of Busan.

In his own remarks from South Korea, General Dunford was also keen to stress that there are no new plans to increase the number of bombers, ships, or other assets assigned to the Pacific region and that the number of assets in the area are essentially “fixed.” “What’s not fixed is the manner in which we integrate all those … things. So when do we do it? What pattern do we show?”

High tech weaponry

But South Korea seems intent on expanding its own long-range arsenal to hold North Korea at threat without necessarily needing American support. When asked about what “higher end weaponry” South Korea wanted to buy, Song specifically and exclusively about long-range missiles.

Earlier in October 2017, the South Korean Army had unveiled a plan to launch a huge missile barrage against the North during the opening stages of any conflict on the Korean Peninsula. That concept relies almost entirely on domestically designed short-range ballistic and cruise missiles, which South Korea is developing with significant help from the United States.

At present, the two countries have an deal in which South Korea agrees not to develop missiles able to fly more than 500 miles or carry a warhead larger than 1,100 pounds in exchange for technical military assistance. Trump and Moon’s have tentatively agreed to change those restrictions amid reports that the South Koreans have already started the basic development work on a new long-range ballistic missile, referred to as Hyunmoo-4.

There is also the very likely possibility that the South Korean Navy will include a ballistic missile capability in its upcoming Jangbogo III-class diesel electric submarines, as well as retrofit such a system onto some of its existing boats. The ability to produce longer range missiles with larger payload capacity would only give South Korea’s military more flexibility in positioning and employing any future sub-launched ballistic missile capability.

And while Song did not mention it specifically, much of what is known about South Korea’s plans to respond to a crisis with North Korea rely heavily on having the best possible picture of where the bulk of North’s nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles, and long-range artillery are positioned at any particular time. In September 2016, the South Korean government had announced a three-tier operational concept, starting with “Kill Chain,” a surgical strike using land-, sea-, and air-launched ballistic and cruise missiles to try and neutralize an imminent North Korean threat.

A constellation of five spy satellites, which South Korea hopes to have in orbit by 2023, along with high-flying RQ-4 Global Hawk drones, able to peer into the North from a stand-off distance using various long-range sensors, were an essential component of Kill Chain. The South Korean Air Force expects to receive its first two Global Hawks in 2018, followed by another pair the next year.

Unfortunately, South Korea has also revealed that there was a massive breach of its military computer networks by North Korean hackers around the time Kill Chain – and the two other tiered responses, known as the Korean Air and Missile Defense (KAMD) and Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR) – became public knowledge. Kim Jong-un’s spies likely compromised the specifics of those plans when they stole some 235 gigabytes of sensitive military documents.

But the missile attack plan the South Korean Army described earlier in October 2017 suggests that the core concept remains largely unchanged from Kill Chain. So, it is possible that Song and Mattis explored how the U.S. government could facilitate the acquisition of additional or new intelligence gathering or other assets to make sure the breach would not limit South Korea ability to respond in a crisis. It seems almost certain that discussions about cyber security enhancements for both South Korean forces and shared U.S.-ROK command and control assets would have been on the agenda.

Missile defense

Although Song appeared to deflect a question about ballistic missile defense, something that may have been lost in translation, the South Korean military is undoubtedly keen to expand its capabilities in this regard. Japan is already looking to purchase the Aegis Ashore system and the U.S. Army recently finished setting up its first Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) battery in South Korea.

It would be hard to imagine that the Trump administration wouldn’t offer South Korea the option of purchasing its own THAAD systems, including the long range AN/TYP-2 radar, as well as becoming a bigger partner in the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense system’s continued development. In the past, South Korea has been wary of becoming more closely integrated in such projects for fear of responses from China, which sees the deployment of these defenses on the Korean Peninsula as a threat to its own nuclear deterrent.

North Korea’s rapid development of newer and more capable ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons seem to be steadily changing that calculus for both parties. The South Koreans could opt to focus on something such as the SM-6 surface-to-air missile system, which is less capable against ballistic missile threats, but increasingly versatile nonetheless, or a similar domestically produced weapon, such as the Korean Medium Surface to Air Missile (KM-SAM), as lower cost and potentially less provocative options, as well.

The U.S. Missile Defense Agency is also working on developing a laser-armed drone to try and destroy ballistic missiles during their initial boost phase. South Korea might be especially interested in such a capability given how close North Korea’s likely launch sites are to its own territory.

Of course, both the United States and the South Koreans will have to weight their choices in implementing these new agreements against whether or not they expect their decisions are more likely to provoke Kim Jong-un to action rather than deter him. As we at The War Zone note routinely, threats, regardless of how American and South Korean officials couch them, feed into North Korea’s massive propaganda machine and confirm the pariah regime’s paranoid fears of an imminent attack or outside attempts to assassinate its leadership.

“What kinds of things have proven to cause [Kim Jong-un] to be concerned? What kinds of things do we believe have actually deterred him from doing things in the past?” Dunford said during his remarks in South Korea. “What things maybe exacerbate a crisis or perhaps have, you know, been counterproductive?”

Since September 2017, the North Koreans have threatened to shoot down U.S. bombers and other combat aircraft during shows of force and suggested they could launch ballistic missiles near Guam or conduct an unprecedented atmosphere nuclear test over the Pacific Ocean. North Korea’s state media reiterated its own deterrent threat in response to reports stemming from Song’s talk of extended deterrence.

“The DPRK is a world nuclear power equipped with powerful capability for preemptive nuclear strike and counterstrike,” North Korea’s Rodong Sinmun newspaper said in an editorial. “Tragic is the fact that the U.S. does not know that its plan on ‘limited nuclear war’ for preemptive attack on the DPRK will be a self-destructive option hastening the final end of the empire of evil.”

North Korea might decide to conduct another provocative missile or nuclear weapons test to coincide with Trump’s Asian tour in November 2017. The American president has already made a number of charged off-the-cuff comments about the continuing crisis, including vague threats of “fire and fury” and dubbing Kim “Little Rocket Man.”

“The United States does not accept a nuclear North Korea.” Secretary of Defense Mattis said himself alongside his South Korean counterpart on Oct. 27, 2017. “Make no mistake any attack on the United States or our allies will be defeated. Any use of nuclear weapons by the North will be met with a massive military response, effective and overwhelming.”

With the new military cooperation agreements, the U.S. and South Korean governments have shown their resolve is as strong as ever, but so far Kim has made equally clear his willingness to defy this sort of international pressure.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com