Whatever you might think of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, it’s safe to say that the Joint Program Office hasn’t had a particularly good week. Reports of hypoxia, cyber security concerns, and the need for a major cost review followed the appearance of a U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) audit, detailing significant and increasingly expensive maintenance issues, which leaked its way to the press ahead of an official public release.

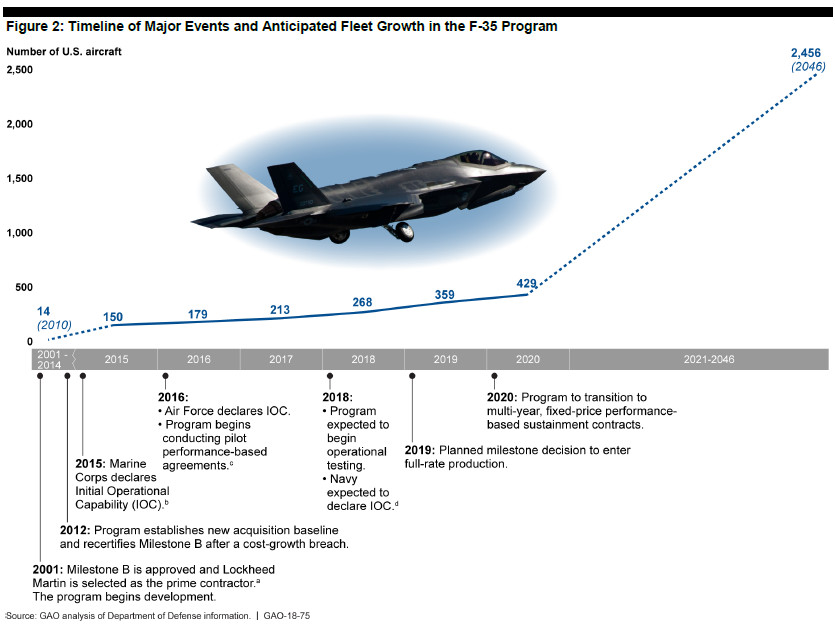

By far the biggest story is the GAO report, which Bloomberg was first to reveal on Oct. 23, 2017, paints a distinctly unflattering picture of the U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps abilities in particular to keep their existing F-35s flyable, breaking down its findings into five core challenges. There’s a major delay in getting depot-level maintenance facilities up and running and a massive spare parts shortage. Beyond that, the Joint Program Office hadn’t even figured out what technical data it would need to support the aircraft going forward and the U.S. Navy and Marines didn’t have vital intermediate maintenance capabilities in place to support planned operational deployments. Lastly, there were serious concerns with the status of the Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS), the cloud-based computer network that is central to keeping the aircraft going on a day-to-day basis.

“These challenges are largely the result of sustainment plans that do not fully include key requirements or aligned (timely and sufficient) funding,” GAO explained in it’s the final public version, which it released in Oct. 26, 2017. The Pentagon “is taking steps to address some challenges, but without more comprehensive plans and aligned funding, [the Department of Defense] risks being unable to fully leverage the F-35’s capabilities and sustain a rapidly expanding fleet.”

That’s an exceptionally diplomatic way of describing the findings, which the Congressional watchdog said were the result, in large of part, of a confluence of mismatched priorities and delays requiring program officials to divert already limited funds. Though this particular report did not mention it by name, GAO has in the past repeatedly criticized the policy of concurrency, in which the U.S. military began buying F-35s before the development cycle finished, requiring repeated and costly upgrades to existing airframes. We at the War Zone have discussed this issue in depth many times, most recently after earlier reports that the Air Force was considering stopping upgrading some of its exist jets to cut costs, but which would leave it with dozens of planes that would be, at best, suitable for limited training purposes in the future.

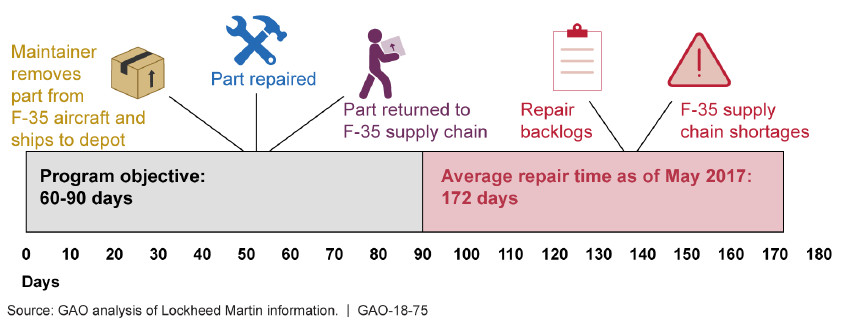

At present, according to GAO, F-35s across the U.S. military were already ending up sidelined because of issues in the maintenance and logistics chains. Plans for an internal U.S. military capacity to perform depot level maintenance on the Joint Strike Fighter are six years behind schedule. As a result, when personnel remove parts from one of the jets for that type of service, they have to send it either to one of the depots that are operational or back to the original manufacturer.

The objective timeline for getting those parts, or suitable replacements, back into the logistics chain is supposed to be between 60 and 90 days. As of May, GOA found that, due to backlogs and shortages, the average timeline was more than 170 days.

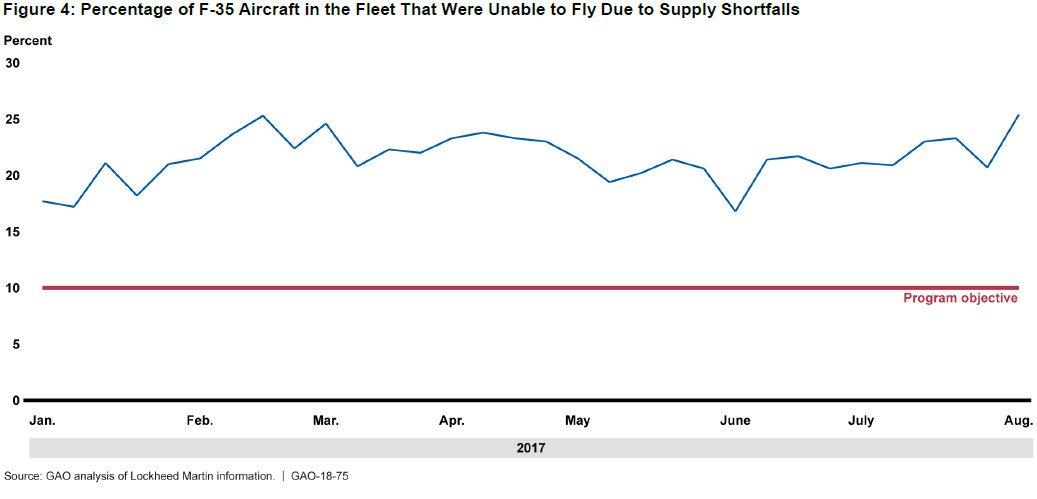

This had contributed to a massive parts shortage that had a direct impact on aircraft readiness rates. Between January and the beginning of August 2017, approximately 22 percent of the F-35 fleet in total across all services on average was not available specifically due to the lack of spares on hand. At some points its was 25 percent or more. In other words, this figure is not an overall availability rate, just the percentage due to lack of spares alone.

Another contributing factor was the continuing lack of agreement between the F-35 Joint Program Office and Lockheed Martin on the transfer of technical data. The U.S. military had yet to even create a comprehensive catalog of all the data it felt it would need to operate and sustain the aircraft.

This had trickled down in the maintenance pipeline, preventing the creation of a complete set of maintenance instructions for ground crews more than 10 years after the F-35 first took to the skies. Without a clear troubleshooting, maintainers were routinely sending parts to the depot when they could’ve made the fixes on site or at an intermediate facility.

Sometimes they would identify the wrong part as the problem and order a replacement only to find that the issue was still there afterwards, requirement more downtime and delays. Personnel at one depot told GAO’s investigators that nearly 70 percent of the parts they were receiving from F-35 squadrons weren’t even broken. Due to protocols, and not knowing for sure themselves, they still had to spend 10 hours testing each one.

The lack of a well established knowledge base within the U.S. military itself undoubtedly helps explain why Naval Air Systems command announced a plan on Oct. 26, 2017 to award a sole-source contract to Lockheed Martin specifically to hire F-35 subject matter experts. The notice did not say how much the deal would cost, but did say that it would support the more than a dozen existing foreign F-35 customers, many of whom are likely dealing with a similar lack of information.

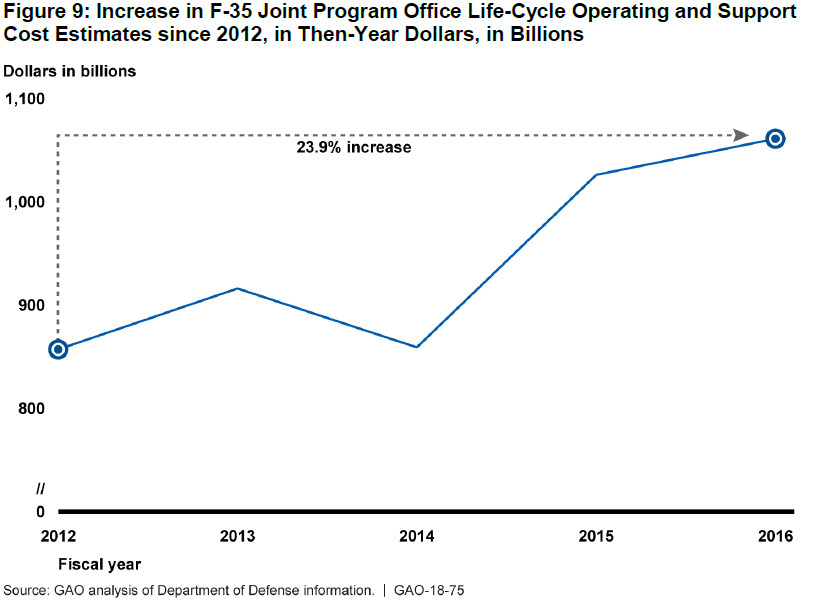

Needless to say, these issues were sucking up time and resources and costing the government millions. This was one of the many reasons why, between 2012 and 2016, life cycle cost estimates for the F-35 fleet had grown by more than 20 percent. During the 2017 fiscal year alone, the Navy and Marine Corps spare parts costs surged from the original budget request of $261 million to more than $400 million.

It should come as no surprise that on Oct. 24, 2017, the U.S. announced there would be major review of the F-35 supply chain and its associated costs. The Pentagon may have hoped this announcement would have headed off the formal release of the GAO report later in the week.

“Lockheed is familiar with this process because we’ve done it before with them, so this isn’t something new,” Shay Assad, the Pentagon’s Director of Defense Pricing told Defense News, somewhat tellingly noting that they had gone through this process at least once in the past. “Many of the things we’re talking about are just practices that have occurred in the past, this will just be much more rigorous. … And we’ll also lay out for them: Here’s our plan in terms of your subcontractor base, and this is what we want to do, and then get off and get the work done.”

Assad specifically told Defense News that the Pentagon had a goal of further reducing the unit cost of each F-35, notably getting the price of a new F-35A model down to approximately $80 million. He did not mention the soaring sustainment costs that could easily outpace any such savings.

We at The War Zone, along with many others, have warned in the past about the fallacy of focusing myopically on unit costs saving. GAO specifically noted that additional purchases above the 250 Joint Strike Fighters the U.S. military is already paying to sustain would only create more stress on the maintenance and logistics chains.

And The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway already discussed how all of this could impact the Air Force’s plan to make the first operational deployment of its F-35As – which already have debatable combat capabilities – to Japan in November 2017 and the availability of those aircraft. The Marine Corps seems to be heading toward its own set of pitfalls since a lack of funds preventing the Navy from establishing adequate intermediate maintenance facilities for the jets onboard its ships.

“Because a funded plan for intermediate-level maintenance is not yet in place, the Marine Corps will not have the desired level of intermediate-level maintenance capabilities for its initial shipboard deployments planned for 2018,” GAO noted. “Accordingly, it will be highly reliant on the currently challenged F-35 supply chain and depot repair capabilities for support, and will likely experience degraded readiness. In addition, without such a plan, it is unclear whether such capabilities will be available to support the Navy’s first planned F-35 shipboard deployments in 2021.”

Hiding in the background of all of these issues have been delays and the potential for more slips in the development of the complex, but essential ALIS computer system, which you can read about in detail here. It seems very likely that any problems with this system, which manages maintenance data and tracks the figurative “health” of the aircraft’s components among many other functions, have only compounded the lack of information when maintenance technicians attempt to diagnose a fault on any particular aircraft.

It might even be one of the reasons why the Air Force has been so far unable to conclusively determine why aviators flying the F-35 at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona continue to report possible hypoxia, a term describing a dangerous lack of oxygen. In July 2017, the service said it was looking into refining the aircraft’s computer algorithm that determines how much oxygen the pilot receives from the onboard oxygen generation system, or OBOGS.

On Oct. 24, 2017, Aviation Week reported that despite the Air Force’s decision to lift flying restrictions and get pilots back in the air, along with the computer code tweak, there had been at least another five reported potential episodes. However, Colonel Ben Bishop, head of the 56th Operations Group at Luke stressed that the Joint Strike Fighters OBOGS was always provide adequate oxygen to pilots and that the system did not immediately notice their symptoms as its programming should do. He said this pointed to possible hypercapnia, or too much carbon dioxide, as the true issue, which could be the fault of a different part of the aircraft’s life support system.

“I think there might be something based on how the machine and the human are interacting that’s altering the breathing,” Bishop told Aviation Week. “So we’re obviously very interested in understanding how the valves are working and making sure our pilots can exhale comfortably.”

In 2016, GAO chided the central F-35 program office over these issues, recommending that it develop a new plan to prioritize and address problems and risks with ALIS. They did so, but in its latest report, the watchdog found that there are still significant concerns, in no small part, yet again, due to budget shortfalls.

“Emerging requirements, such as to address cyber security vulnerabilities and system obsolescence, will likely lead to changes in the Roadmap that could further delay the date when these sustainment capabilities are provided,” the report explained. “Furthermore, the requirements and associated timelines for ALIS development that are identified in this plan may not be realistic because the requirements are not fully funded in upcoming service budgets, resulting in additional risks to the program’s plan.”

The issue of cyber security is one we at The War Zone have stressed numerous times before, especially since the U.S. military expects the F-35 to operate in a networked manner unlike any other previous aircraft. This concern has impacted foreign partners, as well, including Israel, which pushed hard to secure the unique right among foreign F-35 operators to tweak the Joint Strike Fighter’s computer software to its own needs.

In June 2017, I described what a worst case cyber attack scenario could look like for the global F-35 fleet:

“The nightmare scenario would involve an opponent causing a disruption during an actual crisis by either actively feeding bad information into the ALIS system or otherwise disabling some portion of it or its overarching architecture. The interconnected nature of the arrangement might allow a localized breach to infect larger segments of the F-35 fleet both in the United States or abroad or vice versa. It’s not hard to imagine the time and energy needed to sort out real inputs and outputs from fake ones hampering or halting operations entirely under the right circumstances. Given the jet’s low-observable characteristics, advanced defensive systems, and other sensors, a cyber attack would be an attractive option for any enemy force. Why would an enemy use a $500,000 air-to-air or surface-to-air and put their personnel and equipment at risk in an attempt to down an F-35 when a simple worm may be able to do the same to a whole fleet of F-35s? It could also do so with plausible deniability, something kinetic weapons are far less adept to.”

Now the U.K.’s Royal Air Force (RAF) is hiring cyber experts to look for weaknesses in the system. The RAF’s 591 Signal Unit, a counterintelligence element that has historically focused on guarding communications equipment, will manage the cyber defense effort, according to The Telegraph. It is presently advertising for contractors to help with the work.

The United Kingdom has been having its own separate set of F-35 delays and cost overruns, which we at The War Zone have looked at in depth in regards to the Royal Navy’s new supercarrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, which presently has no fixed-wing aircraft. The problems that GAO has identified with the U.S. military’s own program could easily translate to the United Kingdom or other foreign customers, will similarly have to manage the high costs of operating a stealth fighter fleet. The British are already concerned that they will not have enough of their own F-35Bs ready in time that it has signed a deal with the Marine Corps to have its Joint Strike Fighters fly from Queen Elizabeth on her first operational patrol

In the United Kingdom’s own case, the country’s flagging economy in light of its planned exit from the European Union, also known as Brexit, BAE Systems, the main U.K.-based F-35 related defense contractor, slashed some 2,000 jobs earlier in October 2017. Those layoffs that come in the company’s aviation divisions mainly involve the production of the Eurofighter Typhoon, but some will come at its facility in Samlesbury, which builds Joint Strike Fighter components.

The “F-35 program is at a critical juncture,” GAO said at the conclusion of its report. The Pentagon’s “reactive approach to planning for and funding the capabilities needed to sustain the F-35 has resulted in significant readiness challenges – including multi-year delays in establishing repair capabilities and spare parts shortages. There is little doubt that the F-35 brings unique capabilities to the U.S. military, but without revising sustainment plans to include the key requirements and decision points needed to fully implement the F-35 sustainment strategy, and without aligned funding plans to meet those requirements, [The department of Defense] is at risk of being unable to leverage the capabilities of the aircraft it has recently purchased.”

This isn’t a particularly new assessment for us, unfortunately, with The War Zone noting that the Air Force and Navy in particularity are increasingly acknowledging, at least tacitly, that the initial plans to field hundreds of F-35s and do away with the bulk of their 4th generation fighter jets may simply not be sustainable. Just earlier in October 2017, Tyler Rogoway wrote:

“I have always maintained that the most crushing fiscal aspect of fielding a predominantly stealthy manned fighter force is that the cost of operation, especially as the platform ages, will be far greater than the vast majority of the aircraft they replace. Lockheed has claimed that won’t be the case, but there are few metrics, not to mention little logic, available to support such a claim. Although the jet has revised, lower maintenance radar absorbent material coated skin, stealth aircraft have always been maintenance man hour hogs. Combine that with the complexity of the F-35, and it doesn’t take a crystal ball to realize the USAF will have to budget more money for sustainment than it already does for its existing fighter force.”

The obvious hope is that the F-35 program can draw lessons it needs from its rough week, and make the changes necessary to get things back on track.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com