It had a slim chance of ever living up to the hype. The long awaited duel between manned robots from America’s Mega Bots Inc. and Japan’s Suidobashi Heavy Industries ended up being more of a grandiose mechanical tickling match than a “Jaeger” fight to the death.

Seeing that the entire program was largely Kickstarter funded, the let down wasn’t really any great surprise, and maybe we will see a more dynamic battle sometime in the future if the proto-sport of sorts survives. But your craving for a real life version of Robot Jox doesn’t need to emanate entirely from a fictional place. During the atomic age of the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Pentagon built its own massive manned robot of sorts, and its job was far more dangerous than crunching steel with another of its kind.

The real-world giant mecha emerged from the nuclear powered aircraft program that began shortly after the end of World War II. The idea seems insane today, but back then putting a nuclear reactor on an aircraft seemed like a logical step in the right direction for the new technology.

The program morphed into a nuclear powered bomber program and moved its way through different offices over a decade until it was eventually cancelled—thankfully—in 1961. But during its development it became clear that human beings, even ones wearing heavy protective garments, were ill suited for servicing such a vehicle and its radioactive fuel. Crash recovery and cleanup was also a major issue to contend with.

Enter General Electric’s Nuclear Materials and Propulsion Operation, General Mills, and Jared Industries and their innovative giant robot the “Beetle.”

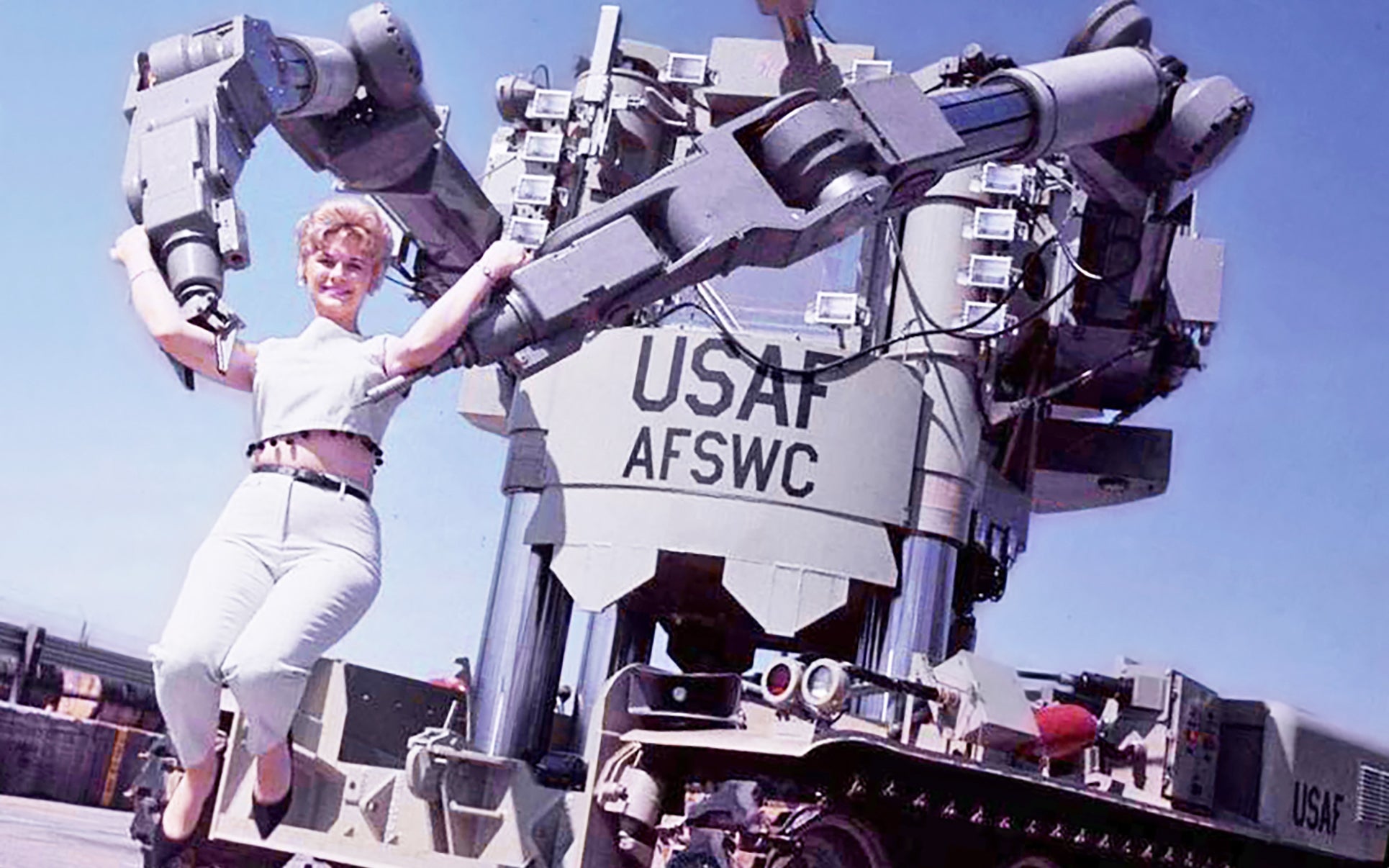

Beetle, which was designed and constructed from 1958 to 1961 at a cost of $1,500,000 for the Air Force Special Weapons Center, was just about as opposite a vehicle as the popular VW Beetle of the era as one could imagine. Built on the tracked chassis of an M42 Duster self-propelled 40mm anti-aircraft gun system, the contraption tipped the scales at a whopping 77 tons. Powered by a 500hp supercharged Continental engine, it had a top speed of just eight miles per hour, and measured 19 feet long by 12 feet wide.

The Beetle’s cube-like cockpit section was mounted on four huge hydraulic pistons, allowing it to rise 27 feet in the air—a necessary feature for working on what would have been a massive nuclear powered bomber. Its interior was shielded by steel armor and a foot of lead plating, and the operator’s viewport was made of multi-layered leaded glass that combined measured two feet thick, allowing the Beetle and its occupant to roll right into highly radioactive environments and perform relatively delicate tasks. The shielding cut down radioactive exposure by a factor of 3,000. An operator could work an entire day inside the vehicle in an environment that would otherwise kill him in just ten minutes.

Once the operator made their way inside, the seven and a half ton hatch was lowered slowly over them, itself operated by four big hydraulic pistons. It also had a battery operated backup pump system that could open the hatch, and a mechanical hand crank on the inside and the outside of the cockpit just in case both other systems failed. There was no other way to escape the tight confines of the Beetle than out of its overhead hatch, so if all else failed an eight hour supply of oxygen bought the operator some time.

The interior of the Beetle was claustrophobia inducing, but it did feature an ash tray, lighter, a very comfortable seat, and a small TV set, among other creature comforts, although the TV was used for monitoring a closed circuit camera system, not for watching I love Lucy. The camera system viewed what was behind the Beetle, like a backup camera today, and a unit could also be attached to one of the Beetle’s arms for seeing close up and around corners. It seems that the idea was getting the hatch opened and closed took so long that making the interior as comfortable a place as possible meant entire shifts could be covered without having to leave the Beetle’s cockpit. But still, there was no room to stretch out walk around.

There was a two-way radio system installed for talking to people outside of the contraption, and even a mic and speaker system was installed so that the operator can hear the engine as they execute maneuvers. A three ton nuclear-biological-chemical (NBC) warfare rated air conditioner kept the occupant cool even when the temperature climbs to Death Valley heights outside. Swing out binoculars were setup in the cockpit so that the operator could quickly read the inscriptions on his tools and gauges over a dozen feet away at the ends of the Beetle’s arms. A periscope also provides a top-down outside view for enhanced situational awareness.

Its powerful hydraulic arms, which were designed based on the configuration of a human’s arms, had over 85,000 pounds of force, enabling them to rip apart metal fuselages or bash over concrete walls, while at the same time the fine motor control was so well tuned that an operator could pick an egg out of a package, hold it in a spoon, and then put it back in the package. A high-profile media event displayed this capability for all to see in 1962.

The ends of the arms could be reconfigured with a number of tools on the fly, allowing the crab-like contraption to work as a multi-function handyman. Its fingers had sockets for different tools to be inserted. The nuclear powered bomber’s components would have also been designed with the limitations of the Beetle in mind.

Although the Beetle was clearly impressive, it was also still very much an experimental design and suffered from constant mechanical issues and breakdowns during initial testing. Its hydraulic system was troublesome—something you simply can’t deal with when handling nuclear materials around an aircraft’s fuselage. Its electrical system, with over 400 miles of wiring, had constant issues. Many of these problems were fixed as testing went on, but other larger issues would have been something the USAF would have been willing to throw money at fixing if the nuclear bomber program hadn’t been cancelled in 1961. This left the completed Beetle without a clear mission and without a good case for additional follow-on funding.

By 1962 it was reassigned as an experimental nuclear accident cleanup device, but considering it needed to operate on flat paved surfaces, its applications were limited. This combined with its astronomical maintenance needs meant the end for the Beetle program.

General Mills’ work on Beetle helped them in creating the manipulator arms for the record setting DSV Alvin submersible, which was first deployed in 1964. And in retrospect, the Beetle concept was a precursor to the robots we have today that are used for all types of dangerous missions, albeit without a human being inside them.

These are namely bomb disposal robots, which are now even used to kill hostile perpetrators, are prevalent in police forces throughout the US and on the battlefield. Similar robots have been used to go where people can’t, including in highly radioactive environments, such as in the battered Fukushima power plant in Japan. Of course we also use unmanned robots that can manipulate their environment to explore the depths of our oceans and other planets, and unmanned ground combat vehicles are finally becoming a growing sector of the weapons industry.

But still, one has to wonder what a more refined Beetle 2.0 would have looked like and been capable of. Supposedly designs for a smaller, more nimble machine were already in the works when the program was cancelled. It almost seems like entire nuclear power plants could have been designed around a family of vehicles like this, allowing for accessibility to radioactive areas and systems even after things have gone horribly wrong.

But alas, it was never meant to be. But knowing of the obscure Beetle, including its genesis and capabilities, does make you look a little differently at the somewhat corny “fighting mechas” built some 55 years after the Beetle first rolled around the tarmac.

Now if we can just get this competition DoD funded right?

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com