The U.S. Air Force’s Small Diameter Bomb II program has seen such large cost overruns that the service will force the manufacturer, Raytheon, to absorb some of the increases, amounting to nearly $40 million. Both parties insist that the present production and delivery schedule won’t suffer, which is important given the present plan is for the precision guided munitions to become a core weapon system for a variety of American combat aircraft, especially the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

On Oct. 18, 2017, the Air Force acknowledged that Raytheon had run out of “financial liability” in its deal to develop the small precision glide bomb, also known as the SDB II or GBU-53/B, as well as in two limited production run contracts. In a not uncommon move, when it signed the deals, the service had set a maximum allowable amount by which costs could grow, with the defense contractor agreeing it could not seek reimbursement for any issues afterward. So far, the Massachusetts-based firm could have to shell out up to $39 million, according to Bloomberg, which first reported the issue.

The company “has worked diligently to address technical discoveries and is implementing the necessary factory infrastructure improvements to meet current contract requirements,” Captain Emily Grabowski, an Air Force spokesperson told Bloomberg. Still, the service “believes Raytheon Missile Systems is able to reliably and consistently build” the weapon.

This assessment is important for both parties, since the Air Force is already planning to buy up to 17,000, as well as help American allies purchase the bombs. Earlier in October 2017, the U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency announced that the U.S. government had approved the sale of 3,900 SDB IIs, plus a variety of other equipment and support services, to Australia, a deal worth approximately $815 million.

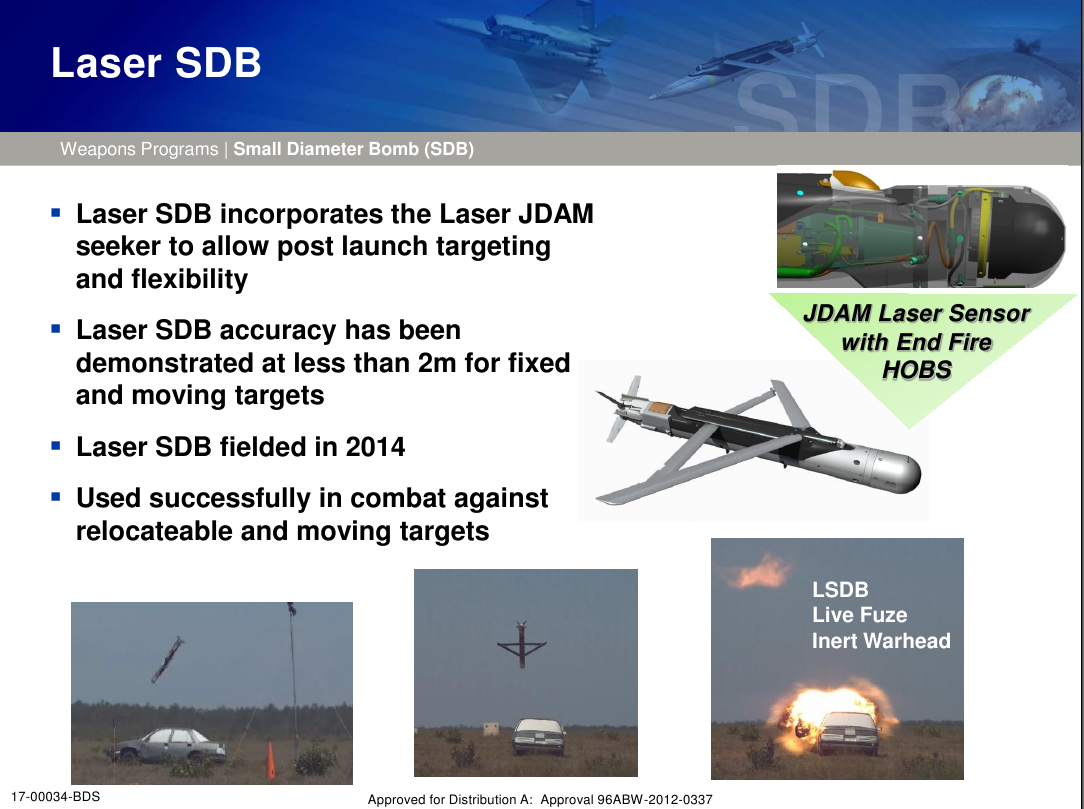

The weapon definitely offers improved capabilities over the older GBU-39/B Small Diameter Bomb and the Laser Small Diameter Bomb (LSDB). The standard GBU-39/B has a combination inertial navigation system and GPS guidance system, while the LSDB adds laser guidance.

The LSDB was already a significant upgrade that also included the necessary software to properly calculate how far ahead of a moving target the bomb has to fly to hit it, known as a “laser-lead” capability. The INS/GPS-directed SDB had no ability to hit moving targets.

Raytheon’s GBU-53/B will have the option of using either of those methods to attack targets, as well as a millimeter wave radar and infrared sensor. This will allow the bomb to find its mark through smoke, dust, and other poor weather conditions, making the weapon truly all-weather capable. The weapon’s on board computer has the ability to classify and prioritize targets on its own, seeking out its especially vulnerable points, too.

It also offers pilots another means of pressing forward with an attack in the event one or more systems malfunction or otherwise get knocked out. The latter point is becoming an increasingly important consideration with regards to GPS, especially as reports of Russian jamming and spoofing increase in Europe. During an actual crisis, those electronic attacks could limit the ability of INS/GPS weapons to function as intended or prompt concerns about their accuracy, making commanders and aircrews wary of using them at all, something we’ve discussed here at The War Zone many times before.

On top of all that, both the older SDBs and LSDBs and the new SDB IIs have pop-out wings on top, allowing them to glide dozens of miles before dropping down on hostile positions or vehicles. This means the launching aircraft to put more distance between it and the target area, potentially allowing the pilot to better avoid enemy defenses or detection, or kill those threats if need be.

Raytheon’s improved bombs have an approximate stand-off range of between 40 and 45 miles, depending on the target type. They’re also networked, which lets the pilot, using information provided by their own board sensors, from other aircraft, or troops on the ground, point the bomb toward another target while it’s in flight to respond to rapidly changing situations.

By all accounts, the program seems to be progressing well. Any new weapon system is likely to have unexpected issues that need fixing, though, and the latest delays and cost-overruns are linked to failed flight and environmental tests.

In 2015, a prototype failed to detonate during a live fire test, requiring a number of unspecified improvements. Raytheon appeared to have resolved that issue, but another weapon’s wings malfunctioned in a test in 2016 and the company had yet to determine the source of the issue as of January 2017, according to the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation. The bomb’s programmable fuze prematurely detonated another bomb during a test of the INS/GPS-guidance mode, but the company resolved that problem.

Perhaps the most problematic issue wasn’t really related to the Air Force’s requirements. In 2016, a prototype SDB II failed an environmental test “related to the shipboard environment,” according to DOT&E. The U.S. Marine Corps and Navy both expect to employ the bombs on their versions of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, which will fly from amphibious assault ships and aircraft carriers.

Raytheon had to rework the basic design to account for “corrosion, temperature, altitude and humidity, and vibration environments,” the Pentagon’s top weapon testing office explained. Though the company declined to comment for Bloomberg’s story, this problem could only have slowed the company’s production schedule and could have forced it to either fix or scrap production bomb or components it had already built.

The Air Force told Bloomberg this pushed the delivery of the first weapons back from November 2016 to June 2017 and delayed the testing and evaluation process. The service now expects to reach initial operational capability with the SDB II on the F-15E Strike Eagle by January 2019.

However, the Air Force is undoubtedly keen to get the new GBU-53/Bs into action as soon as possible, having already spent more than a decade on the program. A major corruption scandal, in which the Air Force’s top acquisition official Darleen Druyun steered the contract to Boeing in exchange for future employment, brought the initial project to a halt and forced the service to run an entirely new competition in 2005. Boeing and Lockheed Martin, which had been the only other company to submit a bid the first time around, joined together on a new submission, but Raytheon won out. It first flight tested its SDB II design in 2009.

In the meantime, the utility of a small and accurate 250-pound class precision weapon that is less likely to harm both friendly forces during so-called “danger close” air strikes on enemy forces in close proximity, as well as innocent civilians. In 2008, the Air Force introduced the Focused Lethality Munition (FLM) version of the SDB, which has a lightweight composite shell that disintegrates when the bomb goes off, further reducing the chance that errant shrapnel could cause unintended collateral damage.

So it’s no surprise that the SDB and LSDB have been stars of the campaign against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, where the fighting has devolved into pitched battles over tightly packed cities full of terrorists, friendly partner and coalition special operations forces, and civilians. In 2015, the Air Force warned it was running out of the weapons, along with other precision guided munitions. Two years later, the service reported that it was no longer “on a glide path to zero,” as one official briefing had termed the situation.

The delays in having the weapon ready for the F-35 have been a particular sore spot for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy, as well. In 2012, U.S. legislators even considered cutting the SDB II program altogether given that the Joint Strike Fighters themselves were behind schedule.

We’ve discussed the F-35’s presently limited arsenal in the past in detail and the SDB II would offer a significant additional capability for the jet during many missions, including its controversial expected role as a close air support aircraft supporting troops on the ground. At present, the Air Force’s F-35A and the Navy’s F-35C can only carry one bomb, in the 2,000-pound class or smaller, internally in each of their two weapons bays. These aircraft could carry four SDB IIs instead, allowing them to engage more targets while still remaining as stealthy as possible.

The issue is even more significant with regards to the Marine Corps’ F-35B, which is limited to at most two 1,000-pound class weapons because of the weight and bulk of the large lift fan in the center fuselage that gives the variant its vertical take-off and landing capability. In 2015, the Pentagon’s central F-35 program office, which manages the project for all of the services, acknowledged that the Marine version would need a resdesign to even accommodate the SDB IIs on their special four-bomb rack, something that it has worked with Lockheed Martin to do since then. One picture, seen above, does show a fit check of four of the weapons in the F-35B’s bomb bay, but its unclear whether this is a functional installation yet.

Until recently, the F-35 fleet as a whole lacked the ability to hit moving targets, too. Lockheed Martin found an interim solution by adding the dual-mode INS/GPS and laser-guided GBU-49/B 500-pound bomb, which has its own built-in laser-lead capability, to the plane’s possible load outs. The SDB II won’t be an option for the jets until sometime in 2022. It will be an option for Navy and Marine Corps F/A-18E/F Super Hornets by 2020, though.

These same issues apply to any American ally that is planning to field the F-35. It is no surprise that Australia, which is expecting to buy more than 70 Joint Strike Fighters, is interested in buying thousands of SDB IIs to go along with them.

Hopefully the Air Force’s and Raytheon’s optimism about the situation will be well founded. Given the already heavy use of the existing SDB and LSDB muntions, pilots and aircrews would find the improved SDB IIs a welcome addition on their missions.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com