It made major headlines this past September when Kim Jong Un’s regime threatened to execute an atmospheric nuclear weapons test in the Pacific Ocean. This seemed to be primarily another hate-fueled response as part of ever heightening rhetoric between the U.S. and North Korea, but its roots may have been in a real technological and logistical roadblock Pyongyang’s nuclear program is now facing.

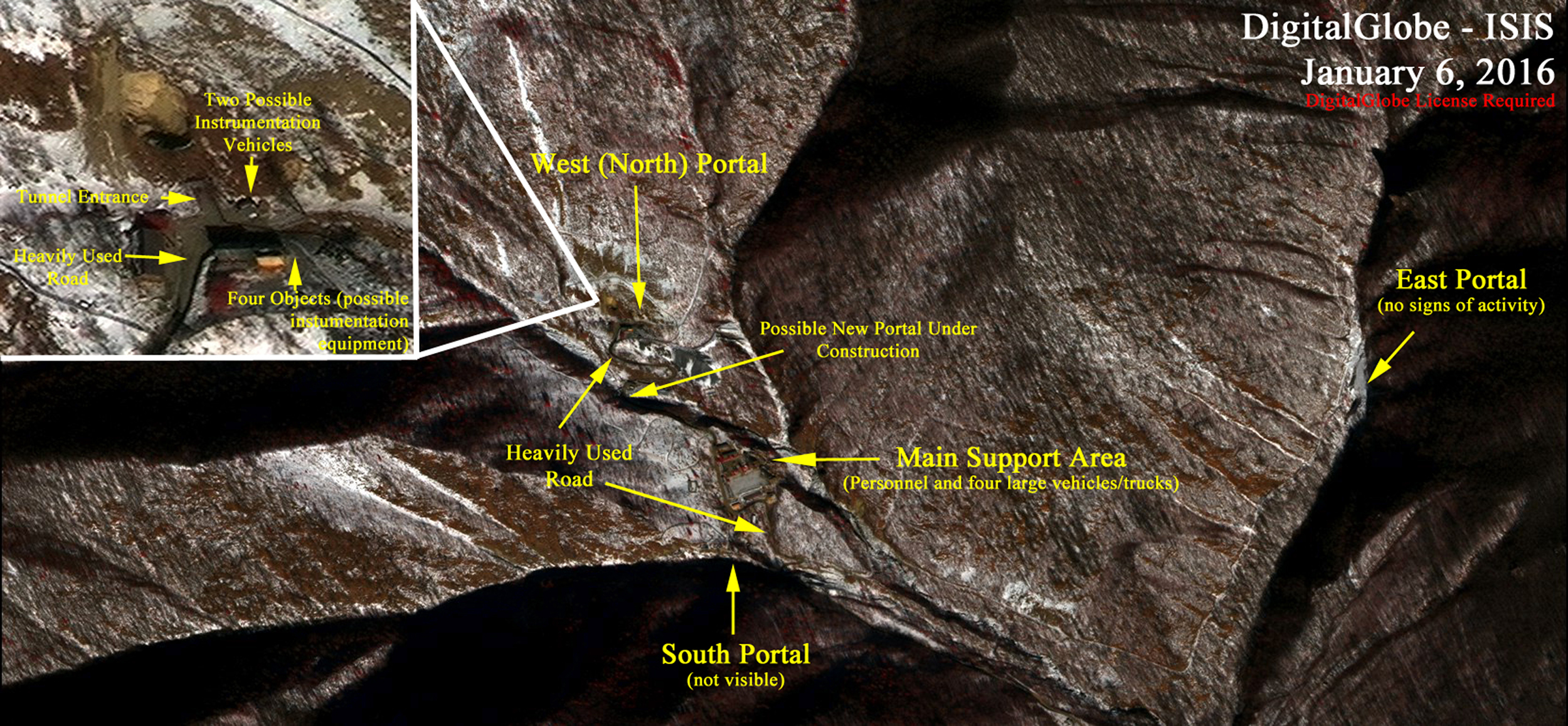

As we have mentioned recently, North Korea’s mountainous Punggye-ri nuclear test site has experienced a series of smaller but significant earthquakes in recent weeks that geologists believe are indicative of the huge caverns created by nuclear detonations falling in on themselves. Satellite imagery has also show large deformations and landslides in the area. This has led to fears of a major radiation release from the site that could endanger people living in the region, including most notably those living on the Korean Peninsula and across the country’s northern border, in nearby China.

It is thought that another nuclear test at the site could be “suicidal” for the regime, not just due to the instability of geological formations in the test area, but also due to weakening deeper down along key fault lines that traverse the area. There are even concerns that further underground nuclear detonations, especially ones as powerful as North Korea’s September 3rd thermonuclear weapon test, which had an estimated yield of some 140kt, could result in a catastrophic eruption of North Korea’s sacred Mount Paektu.

Over 1,000 years ago Mount Paektu had a massive eruption, “something like 1,000,000 nuclear weapons all going off at the same time in terms of energy involved… It’s hard really to imagine the scale” according Clive Oppenheimer, professor of vulcanology at Cambridge University. Oppenheimer was allowed to inspect the mountain during a rare visit to the Hermit Kingdom, and even though its three mile wide crater, known locally as “Heaven Lake,” might look placid, the volcano below is showing signs of activity once again.

All this is very concerning, and it should be especially so for North Korea itself. In essence, they have destroyed their own test ground, in part due to their own success. The test on September 3rd of a much more powerful weapon, roughly eight to ten times more powerful than anything they had tested before, clearly accelerated the failing integrity of the test site.

Even a radiation leak from Punggye-ri caused by past tests could be a major geopolitical blunder for North Korea, as China, which is already cooling its relationship with Pyongyang to some degree, would likely be forced to make even larger moves to isolate the regime if its own people were affected by its nuclear weapons development program.

With all this in mind, North Korea may have no other choice but to move to atmospheric testing if it decides it must continue to make large leaps with its nuclear program in the near term. It is possible another test site may be identified, but preparing it for testing, including coring out the long tunnels for such activities, would take time.

Testing a nuclear weapon somewhere in the Pacific would also serve as a massive escalation, which may be a wanted or unwanted result by the regime depending on who you ask. The last atmospheric nuclear test was by China in 1980, and setting such a precedent once again wouldn’t be good news for the international community to say the least. Additionally, the fallout could be a major issue as well, as the jetstream picks up the radioactive particles and blows them westward.

Kune Yull Suh, professor of nuclear engineering at Seoul National University, stated recently:

“It’s likely that North Korea will conduct its next nuclear test in the stratosphere, or about 100 to 300 kilometers (60 to 185 miles) from the ground, where it will be able to conduct more powerful detonations.”

A high altitude test could also have major impact on electronics on nearby islands and vessels due to the weapon’s electromagnetic pulse. Many theories exist on just how much impact a high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) would have on modern technology. Some say it would destroy nearly every unhardened electronic device across huge swathes of territory, basically setting man back to a pre-electricity age in an instant. Others say that a HEMP would have less consistent effects, with the power grid and its long power lines being most vulnerable.

What we do know is that during the 1962 high altitude atmospheric nuclear test over Johnston Atoll dubbed “Starfish Prime,” electrical systems in Hawaii, some 900 miles away, were adversely affected, with many components being totally destroyed. Keep in mind this was a time before integrated circuits—which are most vulnerable to the fast E1 component of an EMP, were in virtually all electronic devices. Also, one third of the satellites in orbit at that time were also destroyed due the weapon’s secondary effects, with more failing months after due to malfunctioning electronic components.

Fast forward to today, and America’s top general in charge of the country’s sprawling nuclear arsenal sees HEMP attacks as a very real threat. But even he doesn’t seem to know exactly how bad the results of such a strike would be. Of course yield of the weapon and its optimization for an EMP attack matter, as does its height at detonation.

North Korea recently made threats relating to an EMP attack. In fact, shortly before testing their thermonuclear warhead they said it was intended to be used as an EMP device. So they are very familiar with the asymmetric impact such an attack can have on its enemies—all of which rely on intricate electronics far more than they do. As such, testing a weapon high in the atmosphere would give the North Koreans better insight into exactly how EMP’s work and what effects they have on modern electronics and electrical systems.

The big question is how would they execute such a test? There are some misconceptions in the media about this. Most assume they would fire a missile from their own shores into the pacific, where the warhead would detonate somewhere along its flight path. This is may be the most probable method, but they could also sail a cargo vessel into the area and launch a short-range ballistic missile on a high parabolic trajectory and have the weapon detonate downwind from the vessel at a relatively safe distance. It is unclear what the U.S. and its partners would do to stop such a test if it couldn’t be hidden from the watchful eye of their maritime patrol assets. If detected, would the ship be raided or even sunk?

Theoretically, such a test could even be accomplished by North Korea’s lone Sinpo class submarine which can carry a single KN-11 “Polaris” submarine-launched, medium-range ballistic missile. Past test launches have used submersible barges or the submarine at fairly close distances from shore. Sortieing far out in the pacific is likely beyond North Korea’s capabilities now, but that could rapidly change after a number of additional successful KN-11 launches are executed.

With just a single hydrogen bomb test under their belts, it seems that North Korea needs more tests to perfect their device, but the country could also just focus on their long-range missile programs for the time being. This could be at least a tacit sign that the regime sees these weapons more about deterrence and as possible bargaining chips than anything else. If they push for another test in the near term, whether at their crumbling test site or risk potential backlash and even kinetic reprisal from an atmospheric test over the Pacific, it would indicate otherwise.

Seeing how fast things have moved when it comes to North Korea’s nuclear weapons and missile programs, and how steep the nose-dive in the already dismal relations between the U.S., its allies, and North Korea has become, we will probably find out their plan far sooner than we would like.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com