The deaths of three U.S. Army Special Forces soldiers in Niger have brought American operations in the country under new scrutiny. At the same time, the Pentagon has been especially tight-lipped about the nature of the incident, despite a wealth of publicly available information, calling into question the exact nature of the “advise and assist” mission in the West African country.

On Oct. 4, 2017, a still unknown group attacked a patrol of both American special operators and Nigerien security forces in the vicinity of the village of Tongo Tongo, which is less than 20 miles due south of the border with Mali. The next day, U.S. Africa Command, which oversees all U.S. military missions on the continent, confirmed that three Americans were dead, two were wounded, and that “one partner nation member” had died, but little else.

Few official details

“We’re – they’re ongoing operations and we’re gonna – no more details right now,” Dana White, the Pentagon’s chief spokesperson, said during a press briefing on Oct. 5, 2017, which became a common refrain to questions about the attack. “I’m gonna have to just tell you, ongoing operations, we’re not prepared to go in any details on them right now.”

It’s no secret that the U.S. military has ongoing operations in Niger and in neighboring countries. In February 2013, President Barack Obama told Congress, as required by the War Powers Resolution, that he had deployed approximately 100 American personnel to the country in order to run a drone surveillance outfit. In June 2017, President Donald Trump sent his own such letter, indicating that this number had increased more than six fold.

Those approximately 645 individuals “provide training and security assistance to the Nigerien Armed Forces, in their efforts to counter violent extremist organizations in the region,” U.S. Africa Command said in their second press release regarding the Tongo Tongo incident. The U.S. government has previously acknowledged this detail, too.

However, anonymous sources told The New York Times that the Special Forces personnel had been on a “reconnaissance patrol” with their Nigerien counterparts at the time, suggesting that these advisory personnel have been taking an increased role in actual field. This is in line with activities the Pentagon has described as “advise and assist” in nature – many of which seem very close to active combat by any basic definition – in other countries, such as Iraq, Syria, and Somalia.

The 30 minute firefight occurred after the combined group came into contact with a group of militants in technicals in an apparent ambush. The Pentagon has so far declined to officially characterize the nature of the engagement in any specific way.

French helicopters and fixed wing combat aircraft participated in the immediate response, as well as a subsequent operation that Nigerien forces conducted in response to the attack. The Times said that gunships, which would have most likely been Airbus Helicopters Tigers, helped beat back the militants during the incident itself. French media said that other helicopters – either NHIndustries NH90, Aérospatiale Pumas, or Eurocopter Super Pumas – helped rush casualties back to Niamey for medical treatment. Mirage 2000 fighter jets were also involved at some point, according to French media reports.

It’s not clear who called in the French, but both the U.S. and Nigerien militaries closely coordinate with that country’s forces in the region. In August 2014, France began Operation Barkhane, a broad counter-terrorism operation covering Burknia Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger, involving approximately 4,000 French personnel.

There are Tigers and other helicopters forward deployed in the Malian city of Gao, approximately 150 miles northwest of Tongo Tongo, and Mirages in the Chadian Capital N’Djamena, 900 miles or so to the east. More transport helicopters could have been situated in Niger’s capital Niamey, where France has based its MQ-9 Reaper and EADS Harfang drones. French task forces routinely conduct dispersed operations, as well.

Pentagon spokesperson Dana White would not say whether or not there was any American air support on call. The Times reported that drones were operating in the area from the U.S. Air Force’s own base in Niamey.

A rough neighborhood

It’s hardly surprising that U.S. forces are in Niger, given its particularly strategic location. As a center point for the Pentagon’s counter-terrorism efforts in North and West Africa, grouped together under an overarching operation nicknamed Juniper Shield, there are few better countries.

To the north, there is Libya, where militants and terrorists have exploited the chaotic situation that followed the ouster of long-time dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, in no small part thanks to a NATO-led, United Nations-backed coalition. Most recently, a faction of ISIS has emerged as a continuing threat in that country’s central desert after American-backed forces loyal to the internationally recognized government in Tripoli ousted the terrorists from the coastal city of Sirte.

The situation in Libya also opened the flood gate for militants that Gaddafi had supported, including ethnic Tuaregs, to blitz across Algeria and Niger and into Mali, where they joined together with Islamist terrorists. Their rapid gains in 2012 precipitated a crisis that led to the Malian military to depose that country’s president, Amadou Toumani Toure, after they became infuriated with his poor handling of the situation. The United States later acknowledged it had bungled earlier attempts to train Mali’s security forces.

With American backing, France intervened, eventually turning things over to a United Nations approved peacekeeping mission in 2013. United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, also known by its French acronym MINUSMA, remains in the country today, along with a European Union-run military assistance mission and a limited American military presence also tasked with aiding the country’s security forces.

Since 2013, various militant groups have repeatedly split, reformed, and reformulated themselves as a host of different organizations, routinely experiencing friction due to competing agendas and ideologies. Underscoring the complexities of keeping these entities straight, in March 2017, a portion of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the Tuareg-Islamist group Ansar Dine, and another Al Qaeda-linked umbrella organization known as Al Mourabitoun, announced they had joined forces to form Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), or the “Group to Support Islam and Muslims” (GSIM).

On top of that, in 2016, another ISIS-aligned faction, Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) emerged in Mali. ISGS is made up of members of Al Mourabitoun who had declined to re-dedicate themselves to Al Qaeda’s cause.

As if all of this weren’t enough, to the south, Niger borders northern Nigeria, where yet another Islamist group, Boko Haram, began its own reign of terror in 2009. The group prompted international outrage in 2014 when they kidnapped more than 250 school girls from the town of Chibok. In 2015, its leadership declared they become part of ISIS, sometimes referring to itself as the Islamic State-West Africa (IS-WA).

Though it seems likely that one of the groups in Mali was responsible for the attack near Tongo Tongo, given the proximity to that country’s border, it is possible that any of these other regional groups could have been involved in the ambush. An official U.S. Defense Media Activity news story described the incident under the subheader “Fighting Al-Qaida in Africa,” but it was unclear if this was an indication that JNIM or another Al Qaeda faction was behind the assault. There’s always the potential for a new group to present itself or for the militants to ultimately turn out to just be smugglers or bandits who also make use of the regions many unpopulated and therefore ungoverned spaces.

A quietly expanding mission

With all of these security concerns, it makes sense that the U.S. military would be interested in Niger. This wasn’t always the case, though.

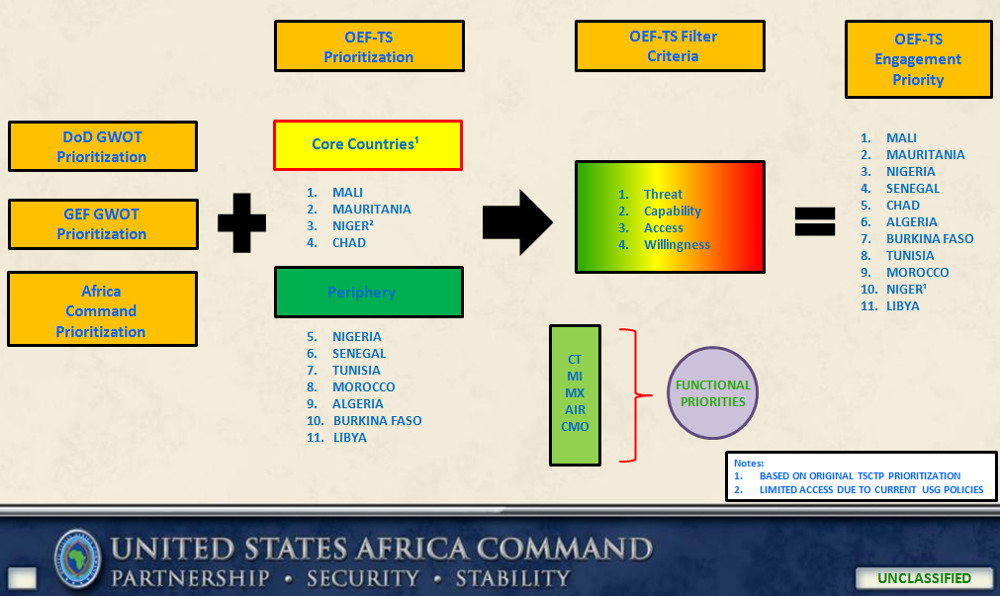

As of 2011, U.S. Africa Command had it second to last in “engagement priority” of 11 countries in the “Trans-Sahara” region, also known as the Sahel, which separates North Africa from the true Sub-Saharan part of the continent, according to one official briefing.

Libya was dead last in importance to the overarching mission, then known as Operation Enduring Freedom-Trans Sahara, or OEF-TS. This was the military component of a whole-of-government effort to bring together countries in the region known as the Trans Sahara Counter Terrorism Partnership (TSCTP).

Niger was placed so low due in part to unspecified “limited access due to current USG [U.S. government] policies.” Critics do say that Niger’s President Mahamadou Issoufou, who has been in charge since 2011, of effectively being a dictator, accusing him of various human rights abuses. Those same complaints apply to almost all of the members of the TSCTP, though.

Regardless, when Gaddafi’s government collapsed and took Mali with it, things quickly began to change. In 2013, under President Obama’s direction, the U.S. Air Force stood up the 409th Air Expeditionary Group, Detachment 2 to manage an unspecified number of MQ-9 Reapers flying from an American managed portion of the Nigerien Air Force’s Base Aérienne 101, itself tacked onto Diori Hamani International Airport in Niamey.

The Reapers’ main job initially was to help keep tabs on the situation in Mali, feeding information back to American and French personnel on the ground as part of an effort that eventually became known as Operation Juniper Micron. The 768th Expeditionary Air Base Squadron eventually came to manage day-to-day activities at the so-called at the site.

A year after Obama first announced the drone operation, Niger’s then Interior Minister, Massoudou Hassoumi, implied to Radio France Internationale that having American and French forces present was the least those countries could do after throwing the entire region into chaos by deposing Gaddafi in Libya without having a clear plan to stabilize the situation. The countries responsible for that should “provide an after-sales service” and intervene in Libya again, he said.

As the fighting in Mali dragged on, the situation in Libya didn’t stabilize. Just the opposite happened and in July 2014, U.S. Marines helped the remaining U.S. embassy staff in Tripoli evacuate to neighboring Tunisia. There had been something of a surge in terrorist attacks in Algeria, too, thanks to many of the same groups operating in northern Mali.

By the end of 2014, the U.S. military had begun working to expand the facilities at the Nigerien Air Force’s Base Aérienne 201, attached to Manu Dayak International Airport in the city of Agadez far to the northeast of Niamey. The United States’ planned establish the necessary facilities for another MQ-9 Reaper operation, set to be ready soon, according to Stars and Stripes. U.S. military and contractor-operated manned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft also operate across Africa.

Today, the 724th Expeditionary Air Base Squadron manages the goings and comings of American aircraft and personnel at Agadez. The 409th Air Expeditionary Group has moved its main base of operations to Niamey, inactivating the separate Detachment 2. Detachment 1, which managed drone flights from the Seychelles for a time before moving inland to Arba Minch in Ethiopia, also no longer exists.

Boots on the ground

Though the drone missions command the most public attention, they reflect only a small portion of the activities the Pentagon has publicly, though discreetly, acknowledged in Niger. In 2015, the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), the U.S. military’s main logistics arm, bought and prepositioned aviation fuel at Zinder Airport, less than 100 miles north of the Nigerian border, to serve as a pit stop for American aircraft.

More recently, in August 2017, DLA issued new contract documentation for fuel purchases across Africa. The list included planned deliveries of gasoline and diesel fuel, the kind of things you need to run trucks and mobile generators, for another five locations scattered around the country. The money would come from accounts linked to Special Operations Command Africa, the lead organization responsible for the Trans-Sahara military assistance mission, which had morphed from OEF-TS into Operation Juniper Shield sometime in 2013.

At present, special operations activities in the region are coordinated by a forward deployed headquarters known as Special Operations Command Forward – North and West Africa, or SOCFWD-NWA. Among other things this organization runs the annual Flintlock special operations exercise, which generally rotates to a different country each year. This year’s iteration involved dispersed drills in Burkina Faso, Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia.

The sites in Niger that DLA’s listed contract documents are almost assuredly where both U.S. special operations and conventional forces perform these training and “advise and assist” missions with the Nigerien military, including the one that American special operators were on when they came under attack near Tongo Tongo. One of these locations, Ouallam, is roughly half way between Niamey and this small village and it might have been where the personnel on patrol were based.

It’s not clear how well staffed or supported any of these locations are on a day-to-day basis. It is entirely possible that Americans only temporarily occupy them during specific training events, staying at larger facilities in populated centers like Niamey the rest of the time.

We do know that just getting from one to the other can be dangerous given Niger’s limited infrastructure. The United Nations placed the desperately poor country second to last in the world in its Human Development Index for 2016. Central African Republic was lowest on the list.

In February 2017, a member of the U.S. Army’s 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne) died during “routine administrative movement” – that is to say traveling, likely by car or truck, from one location to another – somewhere in Niger. In 2015, the 3rd transitioned from focus on operations in Afghanistan to missions in Africa, taking the place of the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) as the main provider of special operations forces for activities on the continent. Though the Pentagon has not publicly confirmed it, anonymous sources have told various media outlets that it was Special Forces soldiers from this unit that died in the ambush eight months later.

A high risk location?

We don’t know whether or not the remote and austere nature of many of these sites in Niger puts American personnel at any higher risks should they become seriously injured for any reason. Pentagon spokesperson Dana White did not answer questions at the Oct. 5, 2017 press briefing about what sort of on-call medical support was available, if any, at the time of the attack in Tongo Tongo.

There is an indication that there might be additional dangers simply due to Niger’s geography and the distance between major population centers. In the January-March 2017 edition of Special Warfare, the Army’s official special operations journal, Colonel Robert Wilson, a former commander of the 3rd Special Forces Group, painted what seemed like a pretty bleak picture.

“Prolonged field care and sustaining a casualty for a very long time is something very different than what we find in the continental United States. We are spread out with limited medical resources in a very challenging environment with tremendous threats from not only the enemy but also from the geography, which is new to us,” he explained. “Our surgeons and our Special Forces medical sergeants are doing a phenomenal job taking a new approach medically. It affects our mission and how we prepare for our mission.”

Since at least 2014, U.S. Transportation Command, by way of the U.S. Navy and Air Force, has managed a contract to stage one fixed wing aircraft and one rotary wing aircraft at Niamey to support personnel recovery, casualty evacuation, and airlift services on a 24 hours, seven days a week basis. Draft contract documentation stated that firm providing the services could typically expect 48 hours notice before a mission, but would have to be ready to go within three hours. At the direction of the local commander, they could end up on a one-hour alert posture. Each aircraft had to be able to accommodate four casualties on litters at a time.

In August 2017, the U.S. military approved a request to award a contract to straight to Berry Aviation without a competition to continue to providing this support. Transportation Command officials argued that they needed to keep the company at work while it solicited bids for the next deal in order to prevent there being a gap in the critical service.

“In Africa, the medical conditions requiring CASEVAC [casualty evacuation] services are typically related to wounds from enemy fire or fighting,” the so-called Justification and Approval document explained. “There is no ambulance or emergency medical service to support the US military in these austere locations, other than the contracted services requested. The need for these critical support services is so urgent that providing a fair opportunity would jeopardize the lives of the US military members in the area which is not acceptable.”

We do not know what the status of Berry Aviation’s aircraft in Niamey was at the time or whether they were conducting other missions at the time. According to earlier contract documents, the two aircraft are available to commanders throughout North and West Africa, not just Niger, as necessary. We know contractors ferried an airman in need of unspecified medical care from a location in Niger to the Landstuhl military hospital at least once in September 2016.

Under the microscope now

“That’s an operational issue that I’m not going to discuss,” White insisted at the Pentagon presser when asked about casualty evacuations. “Partner operations are ongoing even today, so I’m not going to be able to go into any more detail on that.”

But the Pentagon’s reticence to discuss this issue, and virtually anything else about the attack in Niger, seems curious given the extent of what is known about the U.S. military’s operations in the country. Part of that could be due to President Trump’s instance that the United States has given too much information away to its enemies in the past, promising during his campaign and after winning the election to withhold more details about overseas military activities.

It could be due to reticence on the part of Niger’s own government to acknowledge the extent of their cooperation with the U.S. or French military. While many African governments are keen to accept support from the United States, they are well aware that their citizenry may feel that it is evidence of an emerging neocolonial relationship and another reason to criticize their authority.

It’s unclear how long the Pentagon will be able to continue withholding any real official information, especially if there is any suggestion American troops were in harm’s way without adequate support. The dead and wounded American special operators have already forced the U.S. military to acknowledge the basic details of this bizarre incident.

Update:

On Oct. 6, 2017, CNN reportedthat anonymous U.S. sources had told them that rescue forces had found a fourth U.S. Army Special Forces soldier dead in Niger after they became separated from the main group during the attack near Tongo Tongo. Later that day, White House spokeswoman Sarah Sanders confirmed this information, according to The Washington Examiner.

CNN also noted that, in addition to French forces, more Special Forces soldiers had arrived in the area from the United States and the U.S. military positioned a U.S. Navy SEAL element at Naval Air Station Sigonella in Sicily, Italy, a common staging point for American response forces into Africa. The Navy special operators did not ultimately deploy to Niger.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com