The U.S. Air Force still is pushing ahead with plans to modernize its intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) force as the Pentagon continues to work through its latest nuclear posture review, which will likely decide the future of that entire leg of America’s “Nuclear Triad.” In the meantime, the service is still conducting smaller more immediate projects to update the dated infrastructure supporting this deterrent arm, including replacing huge tape-based data systems that personnel used to reprogram missile launch codes and other data.

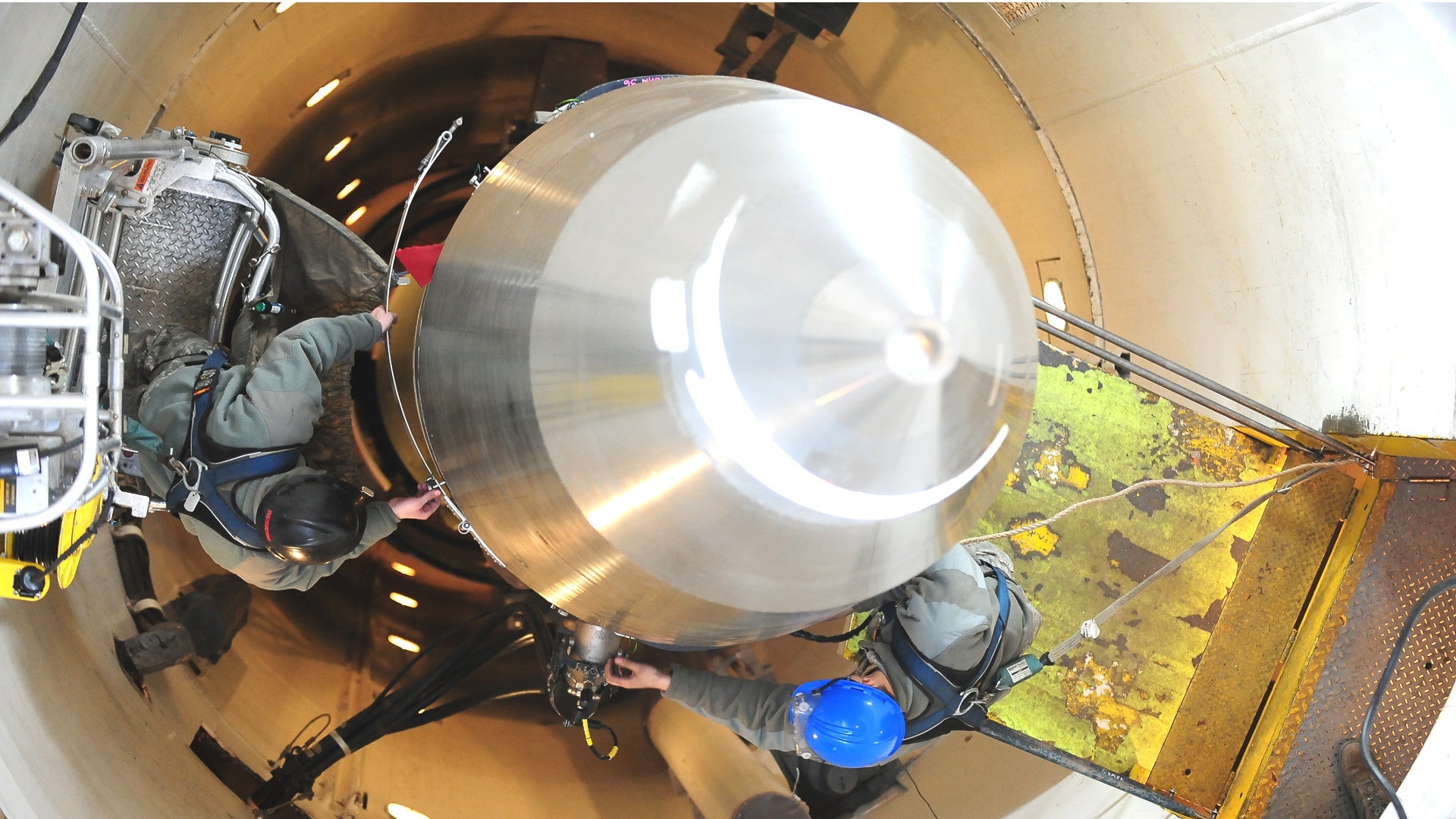

On Oct. 2, 2017, the Air Force reported that the 91st Missile Wing at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota, one of three ICBM wings in the service, had begun using a new information transfer system to upload critical mission information into each individual LGM-30G Minuteman III ICBM. The first of these new Data Transfer Units (DTU) became available in June 2017 as part of a $68 million upgrade program.

“The DTU loads the Missile Guidance Set, which is the brain of the Minuteman III, with sensitive cryptographic data and other information the missile needs in order to function,” U.S. Air Force Captain Kevin Drumm, the codes operations chief at the 91st Operation Support Squadron, explained to the service’s reporters. “The DTU has increased productivity and shortened the time required to conduct coding operations.”

Shortening the time is putting it mildly. Before the upgraded units arrived, the 91st was using a system called the Launch Facility Load Cartridge to program tape memory cartridges with all the necessary data. According to Drumm, it would take 45 minutes to build the data set, which personnel would then spend another 30 minutes loading into a single missile.

On top of that, the cartridge programming equipment was so old that it could only fit enough information for one missile on a single tape cartridge tape unit, which weighed approximately 45 pounds each. The information for each missile is unique for security purposes, so the wing’s code team would need to run through the process 50 times and lug all of the cassettes out to the dispersed launch facilities.

Instead, the new system can build a missile’s full mission data package in 30 minutes and load it into the weapon in less than 10 minutes. Each Data Transfer Unit can hold the information for 12 missiles and weighs just 20 pounds. The Air Force did not say whether the new system is still tape based, which remains a popular high-density data storage format.

All of this saves valuable time and effort during the annual change of codes across the Air Force’s ICBM arsenal, nicknamed Operation Olympic Step, as well as whenever the service might need to update other parts of the missile’s software. U.S. Air Force General Robin Rand, head of Air Force Global Strike Command, which oversees all of the service’s strategic nuclear elements, specifically highlighted the long work hours for missileers supporting the ICBM mission during a panel discussion at the Air Force Association’s annual Air, Space, and Cyber Conference in September 2017.

“They’ll [the missileers] come in about seven o’clock, these younger lieutenants and captains most of them, and they’ll brief up and they’ll get their classified material and they’ll hit the road,” he explained. “They’ll drive as far as three or four hours to get to their ‘office’ and they’ll assume their alert. And they’ll go down on 24-hour alert and they’ll come up and drive those three hours back and then they’ll debrief.”

Individuals will perform these 30-plus hour work “days” between seven and eight times each month, according to General Rand. Support personnel must drive the same distances to get the new code packages out to each of the missiles. Any time savings can be important both to efficient operating and unit morale, the latter of which has become a particularly significant issue for what some have declared a “dead-end career.”

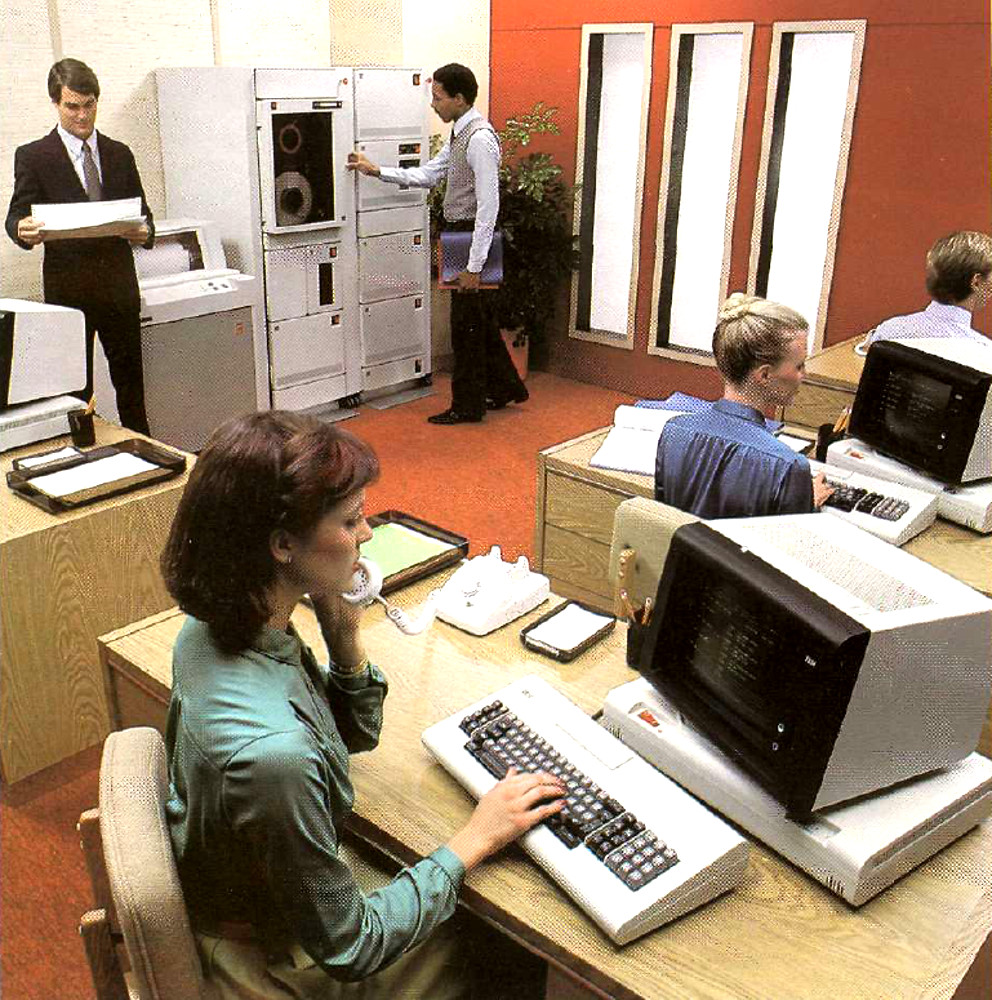

But when it comes to the technology in use, the previous tape memory arrangement was indicative of the generally archaic infrastructure that supports the land-based leg of the Nuclear Triad. In May 2016, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report regarding the increasing age of computers across the federal government, mentioning the age of systems at ICBM launch control facilities, among others.

“The Strategic Automated Command and Control System … coordinates the operational functions of the United States’ nuclear forces, such as intercontinental ballistic missiles, nuclear bombers, and tanker support aircrafts, among others,” the report explained. “the system is still running on an IBM Series/1 Computer, which is a 1970s computing system, and written in assembly language code.”

Introduced in 1976, the Series/1 was a so-called “minicomputer,” smaller than the room-sized mainframes of the day, which IBM made to order in configurations ranging from $10,000 to $100,000. The assembly code language dates to 1949.

In addition, the Air Force’s strategic control computers run off programs on eight-inch floppy disks. In March 2016, the Department of Defense had begun another $60 million modernization effort in light of the increasing age of the hardware.

“Replacement parts for the system are difficult to find because they are now obsolete,” GAO noted. “There is a plan underway to replace the floppy disks with secure digital cards.”

At the time, U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Valerie Henderson, a Pentagon spokesperson, had a blunt response for media outlets asking about why the U.S. military continued to use the long out of production computers. “This system remains in use because, in short, it still works,” she said.

Experts pointed out that, though dated, the Series/1s and its old disks might actually present a serious challenge for opponents looking to launch cyber attacks on the launch facilities. Disconnected from the internet and without a more common way of directly inserting malicious software into the system made them more secure in many ways.

“I’ll tell you, those older systems provide us some – I will say huge safety when it comes to some cyber issues that we currently have in the world,” U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Jack Weinstein, then a major general in charge of Twentieth Air Force, the service’s top ICBM command, had told CBS’ 60 Minutes in 2014. “A few years ago we did a complete analysis of our entire network. Cyber engineers found out that the system is extremely safe and extremely secure on the way it’s developed.”

Though many of the specific details remain classified, Boeing and Northrop Grumman, the two contractors vying for the Air Force’s ICBM replacement deal, known as the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program, have each indicated cyber security improvements are one of the many things they aim to include in their new missiles. They have also indicated plans to improve the modularity of the weapons, to allow personnel to perform upgrades and install updates much faster.

The new Data Transfer Units and any new hardware and software for a future ICBM will have to take cyber attacks, among other threats, into consideration. As we at The War Zone have noted before, as the U.S. military has become more computerized, the dangers to those networks will only become more pronounced. Even if the Series/1 consoles get replaced, the Air Force may decide it makes sense to stick to transferring data to and from the missiles themselves on magnetic tape.

So don’t be surprised if the new GBSDs, when and if they reach the Air Force’s missile units, still rely on mission software packages loaded up from a tape memory cartridge.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com