The idea of flying straight into a hurricane probably isn’t for the faint of heart to begin with, but there are some parts that are just too dangerous for manned aircraft no matter the crew. So, as Hurricane Maria made its way toward the Caribbean and North America, scientists from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) launched Coyote drones into these hard to reach areas of the storm to gather vital information, highlighting just one of many emerging roles for expendable unmanned aircraft.

Between Sept. 23 and 24, NOAA’s WP-3D Orion research aircraft dropped a total of six of the small remotely operated aircraft into Maria’s “eyewall,” a boundary layer between the eye and the rest of the storm where the weather is most severe and winds can reach speeds of 200 miles per hour or more, according to manufacturer Raytheon. The Coyotes gathered air pressure, moisture, temperature, and wind speed and direction data during the flights.

“NOAA is investing in these unmanned aircraft and other technologies to increase weather observations designed to improve the accuracy of our hurricane forecasts,” Dr. Joe Cione, the head of the Coyote program at NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division, said in the Raytheon press release. “The Coyotes collected critical, continuous observations in the lower part of the hurricane, an area impossible to reach with manned aircraft.”

Raytheon offers the seven-pound Coyote as a lightweight, low-cost platform for a variety of roles. Personnel can get the drone airborne from a common launch tube either on the ground, a ship, or on board an aircraft. After launch, a six-foot wide main wing, two rear stabilizers and twin vertical tails all pop into place, giving the pilotless aircraft a distinctive look.

NOAA’s WP-3Ds, originally Navy sub hunters, drop the unmanned aircraft from the plane’s repurposed sonar buoy launchers near the rear. Previously, scientists would release dropsondes, basically small air-droppable and expendable pods carrying similar sensors, from these tubes.

In a hurricane or other tropical storm, with winds often 100 miles per hour or faster, these unpowered devices could easily get knocked off course. Crews would already have to fly relatively close to the specific part they were interested in gathering information about to have any chance of success.

The two WP-3Ds, which NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center has nicknamed Kermit and Miss Piggy after the famous Muppets characters, have radars and other sensors on board. A single Gulfstream IV business jet, called Gonzo after another one of the Muppets, also supports the Hurricane Research Division. The agency has a number of other smaller aircraft for other weather surveillance purposes, too.

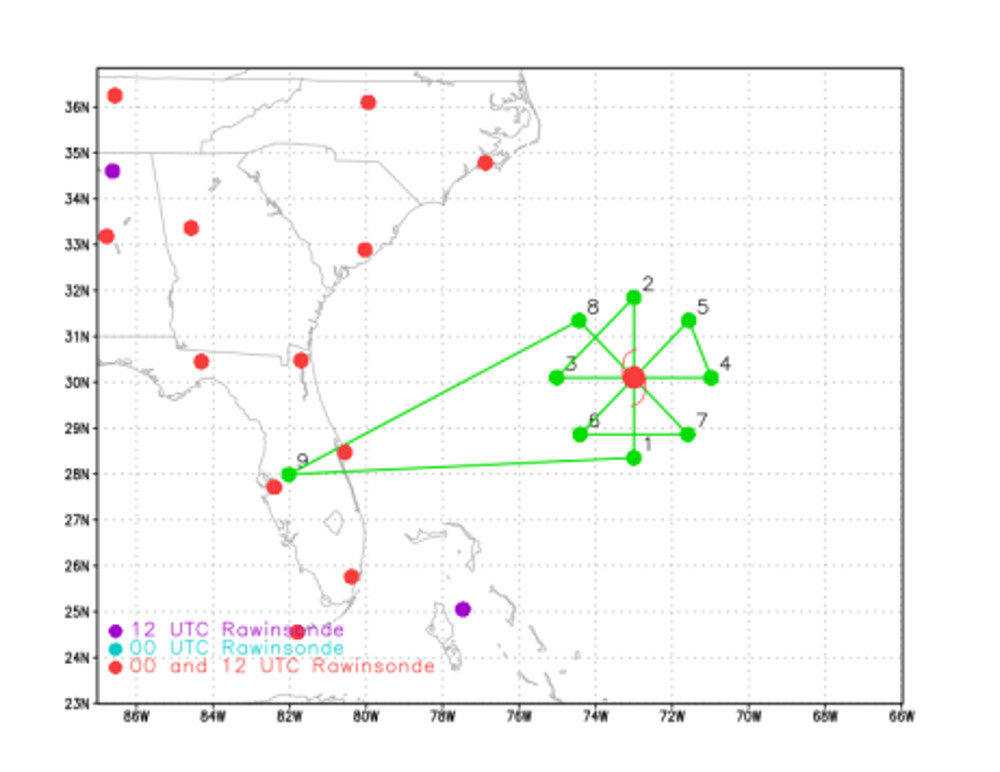

During a typical mission, crews would fly through the storm in a series of straight lines, and also fly around its outer edge. Over the course of the flight, they would employ dropsondes and gather additional information from their radars and other sensors.

“What does get interesting is flying through the hurricane’s rainbands and the eyewall, which can get a bit turbulent,” Chris Landsea, an employee of NOAA’s National Hurricane Center, wrote in a description of flying through the storms for the agency’s website. “The eyewall is a donut-like ring of thunderstorms that surround the calm eye. The winds within the eyewall can reach as much as 200 miles per hour at the flight level, but you can’t feel these aboard the plane. But what makes flying through the eyewall exhilarating and at times somewhat scary, are the turbulent updrafts and downdrafts that one hits.”

Now, with Coyote, researchers can maneuver the sensors into the correct position without exposing themselves to unnecessary danger. A datalink transmits the information back to the Orion so it’s not an issue if the drone ends up destroyed. The Coyotes do have a parachute so personnel can recover them for training purposes.

“Data from these new and promising technologies have yet to be analyzed but are expected to provide unique and potentially groundbreaking insights into a critical region of the storm environment that is typically difficult to observe in sufficient detail,” Cione said in 2014 after NOAA’s first use of Coyote ever as part of the observation of Hurricane Edouard. The agency had purchased the drones with funding Disaster Relief Appropriations Act in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, which caused severe damage to the coasts of New York and New Jersey in particular.

In 2016, NOAA began receiving improved Coyotes from Raytheon. The biggest improvement was an increase in how far away the drones could fly from the controller on the WP-3Ds. The latest models can operate up to 50 miles from the host aircraft and fly for approximately one hour with the research sensor payloads.

Though the researchers have used the drones to supply information about the storms to help forecasters model the possible impacts and predict their paths, NOAA’s main mission remains focused on broader research to improve the accuracy of such data and how scientists gather and analyze it to begin with. These studies contribute to long-term planning and readiness projects, as well as generally increasing the knowledge base of how storms work.

The U.S. Air Force Reserve’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, situated at Keesler Air Force Base in Mississippi, remains the U.S. government’s main hurricane hunting arm. The unit has specially configured WC-130 aircraft, which can release dropsondes, but have no adopted the Coyote drone. The U.S. Navy stopped contributing to the hurricane hunting mission in 1974, according to NOAA.

But the research mission underscores the broader potential of a system like Coyote for both civil and military applications. Raytheon says the drone is big enough to carry cameras and other sensors for military intelligence and surveillance missions. It’s could even carry an offensive payload, loitering over the battlefield for an extended, before striking a target of opportunity. American special operations forces have already put a similar system, called Switchblade, into use in the Middle East and Israeli has mastered the “optionally expendable” drone concept many years ago.

Perhaps more importantly, the lightweight nature of Coyote, combined with a robust network, could allow a group of the unmanned aircraft to operate as single swarm, providing surveillance over a wider areas, a distributed attack on a variety of enemy positions, or other missions. The Defense Advanced Research Projects agency is in the midst of a research and development program to explore the potential of just such a system as part of project appropriately dubbed Germlins.

The same capabilities could be useful in law enforcement or humanitarian relief scenarios, among others, as well. At present, many U.S. civilian government agencies have to rely in large part on the relatively limited views from still and video cameras to rapidly assess damage or other hazards after a major storm or other disaster.

On top of that, NOAA’s operations show it is entirely possible for an aircraft to rapidly launch Coyotes or a similar drone and either control it directly or give it directions to follow autonomously. In the past, the U.S. Air Force has considered adding a similar capability to its AC-130 gunships, which would potentially allow them to spot and track targets beyond the range of their built in sensors or examine them in closer detail from a safe distance before decide to engage.

The latest AC-130W Stinger II and up-coming AC-130J Ghostrider variants, as well as the U.S. Marine Corps Harvest Hawk KC-130 aircraft, already have common launch tubes that are able to fire AGM-176 Griffin missiles and GBU-69/B Small Slide Munition precision guided bombs. It would not be difficult to add Coyote as another option in the arsenal.

Raytheon is already working with the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Research on Coyote as part of its Low-Cost UAV Swarming Technology effort, or LOCUST. The service is interested in swarms of Coyotes for intelligence gathering purposes or even possibly as decoys to distract or confuse an opponent, and any integrated air defenses they might have in particular, during a large scale attack.

The U.S. Army has also expressed interest in the possibility of using the drones to take out hostile small unmanned aircraft, such as the commercial quad- and hex-copter style types that terrorist groups like ISIS have flown in Iraq and Syria. The U.S. military as a whole is slowly waking up to this and other aerial threats, an issue that The War Zone’s own Tyler Rogoway recently explored in depth.

If climate change trends continue to produce larger and more powerful hurricanes, the Coyotes will only become more important to NOAA’s research efforts. At the same time, it’s very likely that we could see the drones, or similar small, low-cost designs end up perform an array of other missions.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com