As the U.S. military approaches two decades of persistent campaigns against terrorists and militants, there has become concern that American troops are increasingly ill-prepared to fight a more capable “near-peer” foe, such as Russia. With this in mind, the U.S. Army has crafted handbook detailing changes in the Russian military, highlighting topics regular readers of The War Zone might already be familiar with, including so-called “anti-access/area denial” weaponry, small drones, electronic and cyber warfare, and the use of proxy forces and propaganda.

The Army’s Asymmetric Warfare Group, a unique special mission unit that includes operational, training, and research and analysis components, published its review of what it called “Russian New Generation Warfare” in December 2016. Public Intelligence, an online clearing house for restricted release, obscure, and otherwise notable government documents posted a copy of the document, which is marked unclassified, but “For Official Use Only,” online.

“Certain things have been bred into today’s Soldier and dictate how we see the battlefield,” the handbook explains in its “purpose” section. “We own the night, the air, have qualitative numerical superiority, our technology is the best in the world, etc. The assumption that we will have these capabilities is inherent to every planning process the Army conducts.”

Unfortunately, as the guide notes in its foreword, America’s potential enemies have not spent the past decade and a half or more idle. The Russian military in particular “barely resembles its former Soviet self” and in many ways has organized itself to match, or at least mitigate, the U.S. military’s often superior technological capabilities.

“How do we protect our troops from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), communications and GPS jamming, and layered air defense networks?” the handbook asks rhetorically. As such, “Our focus at the operational and tactical levels should not be on the “newest kit,” but what we have to do in order to achieve success without it.”

This view in many ways reflects the changing nature of the AWG itself, which came into being in 2006 specifically to help tackle the threat of improvised explosive devices and other insurgent weaponry in Iraq and Afghanistan. The unit has since evolved into a broader “red team” of sorts, studying enemy tactics and equipment and working to identify potential threats and capability gaps in the U.S. military.

It’s no surprise that one of the first topics they’ve chosen to explore in depth is changes to the Russian military and how it operates. Since at least 2014, under the leadership of Russian President Vladmir Putin, the country has embarked on both a massive military modernization scheme and a revanchist foreign policy. Rearmament programs have focused in no small part on advanced weaponry, including new combat aircraft, warships, missiles, unmanned air and ground vehicles, and more. In parallel, there has been a push to form a core professional, volunteer force rather than rely primarily on conscript manpower.

At the same time, Russia has notably seized control of Ukraine’s Crimea region and continues to actively support separatists fighting the government in Kiev, to include deploying troops, intelligence personnel, and contractors alongside them. The Kremlin has sent a major military force to guarantee the continued existence of the regime of dictator Bashar Al Assad in Syria. Moscow is also looking to expand its sphere of influence, particularly in Africa.

“Russian ground forces have updated their military doctrine to reflect these numerous changes in their organization, equipment, and tactics,” the AWG’s guide explains. “Their new doctrine views the military as part of a broader national whole of government approach to warfare.”

At the center of this is the so-called “Gerasimov Doctrine,” named after the present Russian military Chief of the General Staff, General of the Army Valeri Gerasimov. At its most basic, this concept calls for less of a distinction in states of war and peace and the addition of nonmilitary activities, including propaganda and economic restrictions, to military campaigns. Some have referred to this as “hybrid warfare,” but the handbook calls it Russian New Generation Warfare (RNGW).

“The new objective is not victory in a conflict, but regime change,” the AWG manual notes. “Because the new objective is the change of an entire system of government, the RNGW approach can use any lever of influence in their reach to achieve this change.”

Though not stated explicitly, it would seem that these same tools of Russian regime change, as seen in Ukraine, have also been applicable to stabilizing friendly governments. In Syria, Russia has also employed a mix of conventional and special operations forces, along with providing direct support to private military contractors and local forces, including militias and terrorist groups.

But even though the Gerasimov Doctrine might call for a blended military and nonmilitary approach to achieving foreign policy aims, the military component relies heavily on conventional weapons and equipment. The Russians have focused a significant amount of effort on developing and fielding systems that limit the ability of foreign powers, such as the United States, to intervene in response to the Kremlin’s actions.

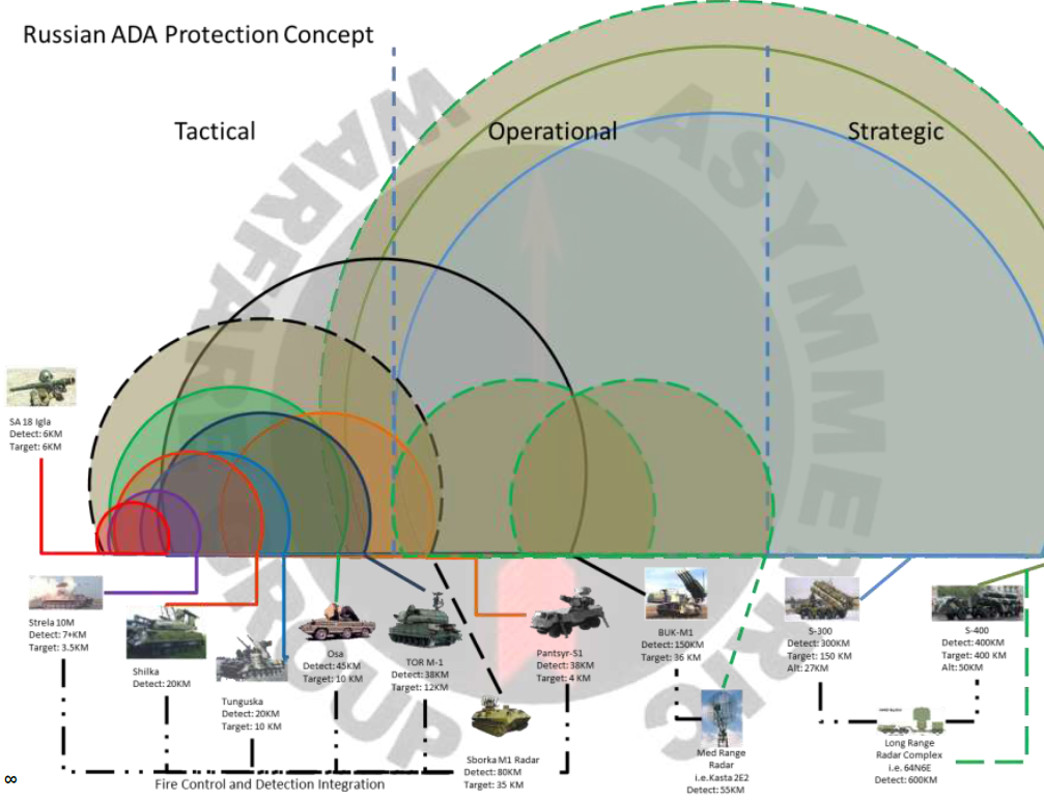

“U.S. forces have come to take air superiority for granted,” the manual notes. “Because of this, Russia has gone to great lengths to develop air defense capabilities on strategic, operational, and tactical levels to deny American’s the use of this capability.”

Russia’s integrated air defense systems, including a wide array of anti-aircraft systems, surface-to-air missiles, and long-range radars, have come to represent a real challenge to American air power both along the country’s borders, such as in and around the Baltic and Black Seas, and around the world. Knowing this, the Russian military has worked to keep as much of this equipment mobile and rapidly deployable, able to move out with task forces as small as a reinforced infantry or armor company.

The ability to rapidly challenge enemy air power was a hallmark of the initial phases of the separatist campaign in Eastern Ukraine, including the infamous shoot down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 by a BUK surface-to-air missile system in July 2014. Smaller man-portable systems claimed a number of Ukrainian combat aircraft and helicopters.

We have since seen similar developments in Syria, where Russia has linked its own integrated air defense arrangement in that country with that of the Syrian government, giving the shared network even more coverage. Though it is unclear how much this has impacted the operations of the U.S.-led coalition fighting ISIS, it would have to be an important planning consideration for both air strikes and ground missions that rely on them.

Long range rocket artillery, tactical ballistic missiles, and land- and sea-launched cruise missiles, serve much the same purpose, providing Russian forces at home and abroad with an important stand-off capability. The AWG’s research suggests that Russian forces see these systems as the “finishing arm” for a final victory in any engagement, rather than just supporting weapons for other infantry or armored forces. Notably absent from these sections, though, is any talk about Russia’s possible changing attitudes toward nuclear weapons on the battlefield.

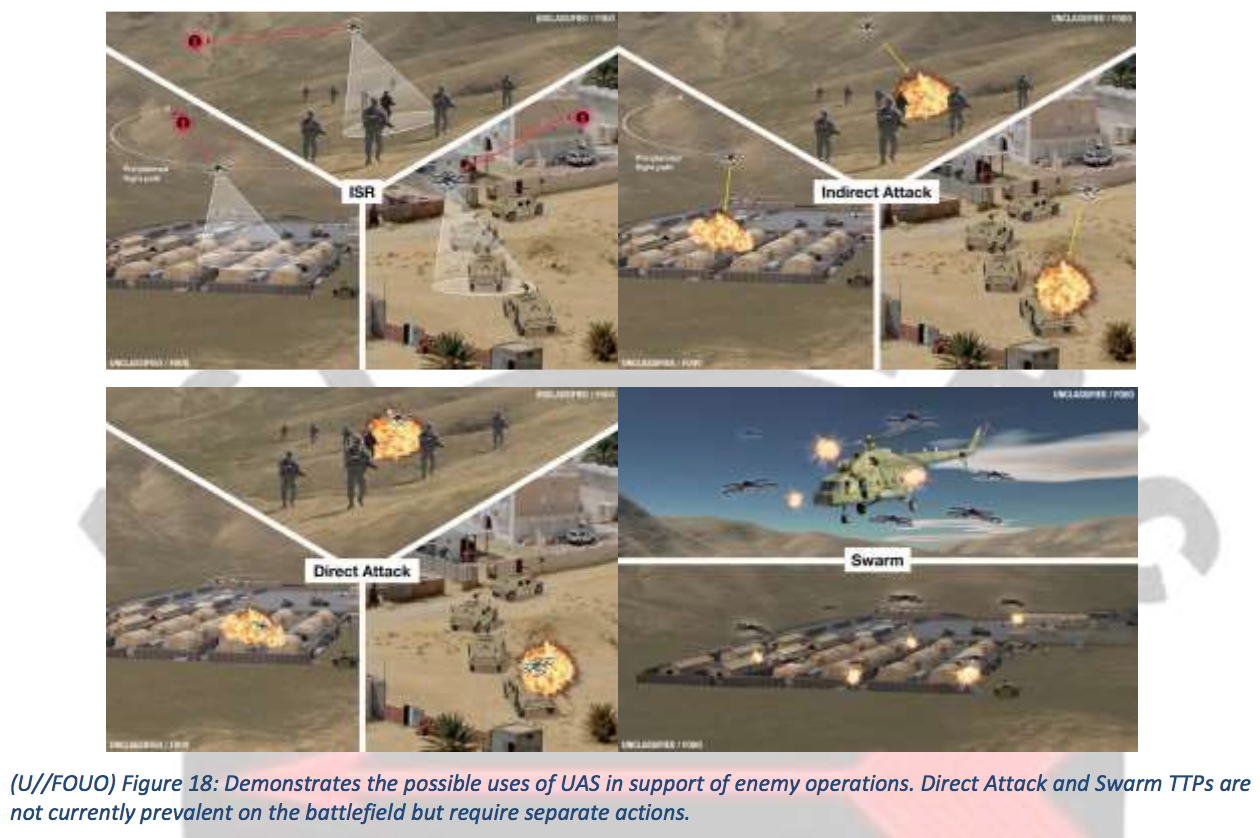

“The employment of UAS [unmanned aircraft systems; drones] by Russian Forces adds another dimension to their fires capability,” the handbook adds. “Russian Forces lagged behind the U.S. with UAS development and employment, however since the 2008 Georgian campaign have made it a priority. Their efforts have paid off, and Russia’s use of UAS has proven to be a game changer in Eastern Ukraine.”

The ability of these drones to spot targets and help artillery units adjust their fire has been especially important given that the Russians lack the kind of precision guided rockets and shells that a pervasive in the U.S. military. According to the AWG, the entire process from getting information from the pilotless surveillance aircraft to adjusting the point of aim and firing another volley can be just 10 to 15 minutes.

So far, the Russian military does not have armed drones, similar to the U.S. Air Force’s MQ-1 Predator or MQ-9 Reaper of the U.S. Army’s MQ-1C Gray Eagle, but the AWG’s guide notes that some of their systems do carry electronic warfare and signals intelligence payloads. Observers have seen Russian proxies employing modified commercial quad- and hex-copter style drones, similar to those that ISIS terrorists have used in Iraq and Syria. It seems only a matter of time and resources before Russia fields a larger, purpose built unmanned combat aircraft, though.

The aforementioned electronic warfare capability has the potential to be just as devastating as a direct attack. Knowing that most modern militaries rely heavily on communications and electronic navigation capabilities, Russia has invested a significant amount on systems to neutralize those advantages.

“The Russians layer these systems to shut down FM, SATCOM [satellite communications], cellular, GPS, and other signals,” the handbook explains. “In Eastern Ukraine, these EW [electronic warfare] systems have proved devastating to Ukrainian radio communications, are capable of jamming unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), and can broadcast false GPS signals (an effect called spoofing).”

On top of that, many electronic warfare systems have the ability to spot and locate enemy signals as part of the jamming process, or even break into unencrypted video feeds. So, in some cases, the Russians have paired these units with artillery elements to offer yet another means of spotting high priority targets.

“Certain platforms are used for protection, emitting … [a] signal designed to overload electronic fuses on incoming fires,” the guide adds. “Guided munitions, both direct and indirect, will either detonate early or change course once they come in contact with one of these … bubbles.”

The Russian military’s focus on electronic warfare has bled over into cyber warfare, as well. Shutting down computer networks could easily give important advantages during a conflict, blind an opponent to up-coming attack, or simply serve to destabilize a hostile country.

“Cyber-attacks can effectively shape the battlefield and require very little risk on the part of the perpetrator,” the AWG’s manual notes. “Since U.S. formations operate under self-imposed restrictions, like ethical hacking and prioritizing protective measures over offensives in the cyber realm, they are limited in their capabilities compared to Russian counterparts.”

Gerasimov’s hybrid warfighting concept means that there is significant evidence that the Russian government actively cooperates with hackers or collectives, or even creates fictitious ones in order to give plausibly deniability to various activities. As we have seen in investigations into Russia’s meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, which Putin has claimed might have been the work of “patriotic” Russians, it can be extremely difficult to separate one from the other.

“The Kremlin cooperates with criminal hacker groups and the Russian government employs thousands of professional hackers as part of their whole of government Information Operations strategy,” the handbook points out. “This severely outnumbers U.S. military cyber capabilities and means that U.S. brigades could be subjected to cyber-attacks from pro-Russian sympathizers in countries not even involved in a conflict.”

The potential impact of information operations campaigns, both combined with and separate from active military campaigns, cannot be overstated and is something the U.S. military has also become increasingly aware of. Russian capabilities in this area are particularly advanced, combining traditional battlefield propaganda with new media tools and the internet.

“Electronic warfare devices allow Russian Forces to broadcast … messages directly against opposing Ukrainian forces as discussed earlier with cellular text messages,” according to the AWG’s guide. “These can be very specific and directed at individuals, such as by threatening their wives and children by name, or generic and sent to entire units as was the case in Ukraine.”

Control of information has also allowed Russia to shape the discourse about controversial conflicts in international forums and shield its own populace from the true costs of war. NATO in particular has become increasingly interested in tools to challenge these narratives and provide alternative sources of information, including via the internet.

Despite the obvious threats to present and future U.S. military operations highlighted in the manual, the AWG’s handbook says its observations are just that and not to be taken as an indication of any official changes in U.S. military doctrine. Still, the unit’s analysts do offer some ideas about how to mitigate these emerging challenges.

The biggest recommendation in the guide is for American training regimens to focus more on alternatives to electronic systems, including land navigation in GPS-denied environments, continuing operations as smoothly as possible during communications blackouts, operating without constant on-call air support, and recognizing, avoiding, and eliminating small surveillance drones. In addition, troops need to be aware of danger of targeted electronic warfare, cyber attacks, and information operations based on their online activities and social media usage.

“The newest cadre of Soldiers, known as the first generation of truly ‘digital natives,’ is often culturally resistant to regulations imposed on their online social interactions,” the AWG manual reminds the reader. However, “a simple, innocuous-seeming post on Twitter or Facebook can now give away location, movement, and military capabilities in the stroke of a key.”

Social media posts and other publicly available information are definitely gold mines of potential information. The U.S. government and independent observers have mined social media and other online pictures and information to prove the presence of regular Russian troops in Ukraine, locate the sites of missile launches and massacres, and even target the enemy.

Of course, the AWG’s guide highlights the flagging Russian economy and the country’s limited resources, something we at The War Zone routinely bring up when talking about the Kremlin’s many military

modernization goals. As such, many of its most advanced systems exist in far fewer numbers than Russia may like to admit or may never enter service at all.

Still, the Gerasimov Doctrine exists in no small as a result of this reality and specifically offers tools to make up for relatively small numbers of certain forces and systems within the formal Russian military. Most of the emerging threats the handbook on Russia’s new form of warfare describes could easily apply to other possibly opponents, most specifically China, making the information and recommendations broadly applicable, as well.

Even if the threats are limited, it is no reason to not plan to defeat them. There’s no indication that the Russians, or other near-peer countries, are slowing their developments in both military hardware and new operational concepts, either. Russia in particular has been able to use both Ukraine and Syria as incubators to see what works and what doesn’t.

“As the saying goes, ‘Only fools learn from their mistakes,” the handbook’s authors write in the foreword. “The wise man learns from the mistakes of others.”

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com