If you happened to glance at Google Earth’s satellite imagery of Naval Air Station Key West in Florida recently, you may have noticed something that might seem odd. A trio of B-1 Bones from the 7th Bomb Wing at Dyess Air Force Base in Texas are sitting on the flight line. The swing-wing bombers aren’t there poised for a strike on Cuba or somewhere else in the Caribbean, but instead as part of a routine, if largely unknown mission that has them looking for drug smugglers.

For more than a decade, the U.S. Air Force has deployed B-1s, as well as B-52H Stratofortresses, E-3 AWACS, E-8C JSTARS (JSTARS), and supporting KC-135 tankers in support of counterdrug efforts in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Unique interagency task forces – Joint Interagency Task Force-South (JIATF-S) situated in Key West and Joint Interagency Task Force-West (JIATF-W) in Hawaii – coordinate these missions as part of a whole-of-government approach. These headquarters bring together members of the U.S. military, U.S. Intelligence Community, and American law enforcement agencies, as well as representatives from other nations in their respective regions.

“Obviously finding boats doesn’t seem like something a bomber would do,” U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Nick Yates, then commander of the 9th Bomb Squadron at Dyess Air Force Base in Texas, said in an official interview in 2016. “We look at this as an opportunity to – we are flying over large amounts of water, which we don’t have in West Texas and integrating with multiple naval-coast guard-type assets.”

“Part of our current mission is to go out and find all types of different targets,” U.S. Air Force Major Michael Flick, Weapons and Tactics Chief for the 9th Bomb Squadron at the time, added. “This gives an opportunity to go down to an area that we don’t typically operate out of and it’s a good opportunity for us to go exercise those combat capabilities that we have and are ready to execute, but don’t necessarily get the opportunity to very much.”

Both men were speaking after Operation Big Week, a week-long surge in existing efforts in support of JIATF-S and U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) in August 2016. These missions also included Air Force manned and unmanned reconnaissance aircraft one might otherwise expect to be involved, along with land-based radar sites the service operates in the Caribbean and Latin America in cooperation with America’s regional allies.

U.S. forces and their partners seized or “disrupted” the smuggling of a total of six tons of cocaine during the operation. Disruption in this case commonly means that the drug traffickers chose to dump their cargo into the sea before trying to flee. The six tons in this one week was two percent of the total amount JIATF-S seized – 282 tons – in the entire 2016 fiscal year.

Unable to directly engage the traffickers, since the goal is to detain them not kill them, the bombers look for the boats, monitor their movements, and pass the information along to naval and coast guard elements on the surface via a centralized air operations centers. Those forces then disrupt or apprehend the suspected criminals.

The use of Air Force and other U.S. military aircraft to hunt for drug smugglers isn’t new, of course. Since the earliest days of America’s controversial War on Drugs, spy planes and other surveillance aircraft in particular

have been key components of the effort.

The United States has arranged deals with various countries to operate a network of so-called “cooperation security locations” and “forward operative locations” around the Caribbean, Central, and South America as launching pads for these reconnaissance sorties. Over the years, the Air Force has deployed RC-135V/W Rivet Joint and C-130 Senior Scout signals intelligence aircraft, U-2 Dragon Lady spy planes, and RQ-4 drones “south of the border” for counter-drug related tasks, with the flights referred to with colorful nicknames such as Palmetto Emerald, Seminole Wind, and Shark Axe.

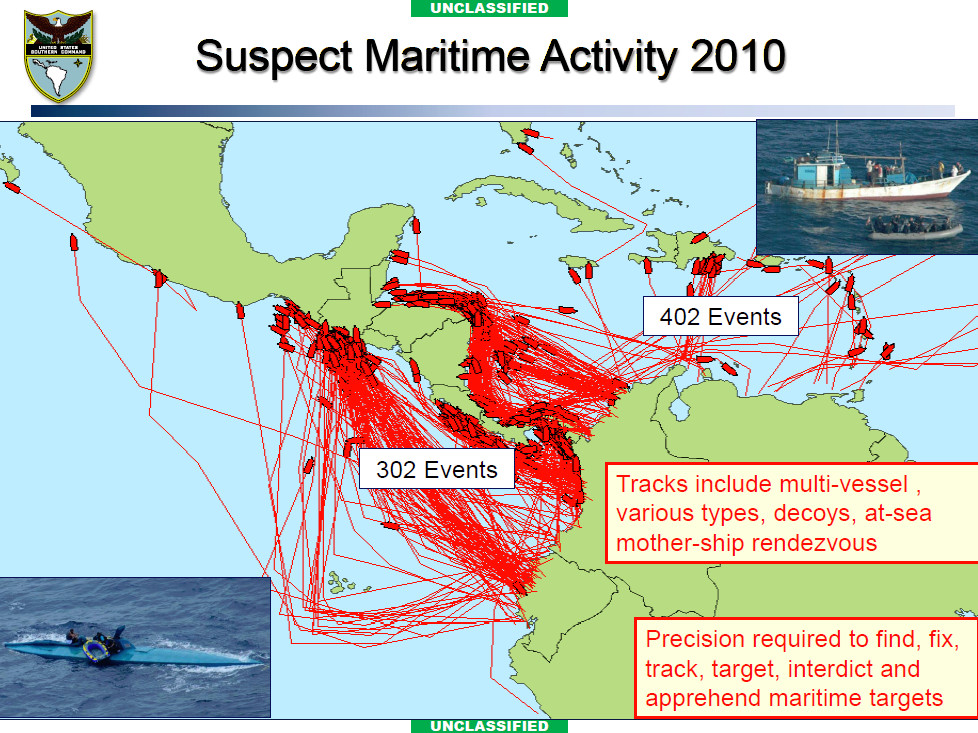

These assets are always in high demand and there’s always a desire for more intelligence. This is especially true when it comes to trying to keep tabs on huge swaths of open ocean in the dead of night. Over the years, drug smugglers have only made themselves more difficult to spot, constructing semi-submersible “narco subs” and other heavily customized boats.

“For the past several years, our Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and other force requirements have not been met due to competing global priorities,” U.S. Navy Admiral Kurt Tidd, head of SOUTHCOM, explained in his annual posture statement in April 2017. “We have felt these impacts most acutely in our Detection and Monitoring (D&M) mission, where we have long received less than a quarter of our maritime and airborne requirements.”

This is where so-called “non-traditional” ISR have come into play. This refers to using combat aircraft, including high performance multi-role fighter jets, in a reconnaissance role, making use of their existing electro-optical, infrared, radars, and other sensors. The targeting pods on F-16 Viper and F/A-18 Hornet fighters for instance can easily double as a surveillance tool.

During the 1990s, the Air National Guard rotated F-15 and F-16 squadrons through deployments to Howard Air Force Base in the Panama Canal Zone for exactly this reason. This mission, nicknamed Coronet Nighthawk, provided what was effectively a realistic training exercise given that drug traffickers had no way to challenge the high-flying aircraft.

But in November 1999, the United States returned the Panama Canal to the Panama and shut down its permanent military presence in the country. When operating from bases in the continental United States and Puerto Rico, the limited range of fighter jets for the over-water surveillance mission became readily apparent.

The Air National Guard ended Coronet Nighthawk deployments entirely in August 2001. After 9/11, the demands on fighter squadrons increased as the domestic alert role gained renewed significance, as well.

Even so, bombers and larger radar aircraft like the E-8C, especially when supported by KC-135 tankers, offer significantly more time on station when operating from state-side bases compared to fighters or attack aircraft. As part of their increasing close air support role, both the B-1B and B-52H now carry the same kind of targeting pods as those smaller Air Force aircraft, as well.

On top of that, there has been a push to revitalize the anti-ship and maritime interdiction roles for American bombers. This is especially true in light of growing operational demands

in the Western Pacific with a particular eye towards countering Chinese claims in regions such as the South China Sea.

In June 2014, the Air Force revealed that it had tested the AN/ASQ-236 Dragon’s Eye active electronically-scanned radar pod on a B-52 bomber, specifically focusing on improving its ability to find and track hostile ships. More recently, earlier in August 2017, a B-1 successfully fired an AGM-158C Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), demonstrating its own expanding maritime capability.

As Major Flick noted after Big Week in 2016, having bombers, as well as JSTARS, fly counter-drug missions in the Caribbean and elsewhere gives crews an opportunity to hone these skill sets against real world targets, but in a permissive environment. It’s also a readily available option in the absence of other alternatives.

“A single JSTARS sortie can cover the same search area as 10 maritime patrol aircraft sorties,” U.S. Marine Corps General John Kelly, then commander of SOUTHCOM, said in his own annual posture statement in 2015. “The use of these types of assets is a ‘win-win’ for U.S. Southern Command and the Services; we receive much-needed assets while the Services receive pre-deployment training opportunities in a ‘target-rich’ environment.”

It’s not necessarily the most cost-effective solution to chronic shortfalls, though, given how expensive it is to fly B-1 and B-52 bombers and the relatively limited “soda-straw” surveillance capability they provide with their targeting pods. A smaller business jet or multi-engine turboprop could easily carry similar equipment at significantly lower cost.

So, it’s not surprising that in his 2017 posture review, Admiral Tidd noted that the Air Force had secured contractor-operated maritime surveillance aircraft to help off-set additional reductions in his already limited airborne intelligence resources. The service has already been working with the Sierra Nevada Corporation for years to operate and maintain a small number of Bombardier Dash-8 reconnaissance aircraft as part of a project first known as Prospector and then renamed Pale Ale. One of these aircraft crashed along the Colombia-Panama border in October 2013, tragically killing four of the six individuals on board.

However, it’s unclear whether the new aircraft have or will fulfill all of Tidd’s command’s reconnaissance needs. In the meantime, As the satellite imagery from March 2017 shows, Air Force bombers continue to be an important, if non-traditional, option.

Hat tip to our own reader “Aerial Imaging” for prompting this story

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com