President Donald Trump has removed a set of restrictions his predecessor, President Barack Obama, had placed on a program that allows the U.S. military to transfer excess equipment to federal, state and local law enforcement agencies, including tracked armored personnel carriers, various kinds of military weaponry, and other gear. The changes are likely to reinvigorate the public debate about the controversial process, also known as the 1033 Program, which continues to be plagued by serious problems.

Announced on Aug. 28, 2017, Trump’s new executive order rescinds the earlier one Obama had signed, which led to the prohibition on the Defense Logistics Agency sending tracked armored vehicles, “weaponized” vehicles of any kind, firearms firing rounds .50 caliber or larger, .50 caliber or larger ammunition, grenade launchers, bayonets, and camouflage uniforms, to police units. The order also resulted in additional controls and oversight of other so-called “controlled equipment,” such as vehicles, aircraft, explosives, and specialized firearms and ammunition. These new requirements included asking requesting agencies to more thoroughly justify their requests for the gear and to submit more detailed plans explaining how they would properly train their personnel in its use.

“(W)e are fighting a multi-front battle: an increase in violent crime, a rise in vicious gangs, an opioid epidemic, threats from terrorism, combined with a culture in which family and discipline seem to be eroding further and a disturbing disrespect for the rule of law,” Attorney General Jeff Sessions said in a speech to the Fraternal Order of Police’s (FOP) national conference on Aug. 28, 2017. “The executive order the President will sign today will ensure that you can get the lifesaving gear that you need to do your job and send a strong message that we will not allow criminal activity, violence and lawlessness to become a new normal.”

The program is formally known as DLA’s Law Enforcement Support Office. The “1033” in the more common moniker refers to the specific line in the defense budget for the 1997 fiscal year that first authorized the program.

Between 1989 and 1997, previous mechanisms had existed for the transfer of military equipment, but specifically for counter-drug efforts. The 1033 Program removed that restriction, allowing the Pentagon to transfer items for any approved law enforcement purpose.

Many, including various police lobby groups such FOP, had expected this change after Trump won the 2016 presidential election. FOP endorsed Trump after, among other things, he promised to reverse Obama’s decision on the 1033 Program. The organization was quick to laud the policy shift in an official statement.

“The previous Administration was more concerned with the image of law enforcement being too ‘militarized’ than they were about our [police officers] safety,” FOP’s National President Chuck Canterbury said in a statement. “In an effort to shut down a single program run by the Defense Department, known as the 1033 program, they restricted access to surplus equipment across the federal government.”

It is important to note that the Obama administration did not shut down the 1033 program and its restrictions had no direct impact on any other mechanism to transfer military equipment within the federal government. FOP’s statement also does not mention the protests in Ferguson, Missouri in late 2014, or the police response, which led directly to the decision to implement the new rules.

The images from those protests, some of which showed police in heavy riot gear atop armored vehicles pointing rifles at unarmed individuals, that sparked a public outcry and a call for increased scrutiny of federal processes such as the 1033 Program. Various media investigations, including numerous Freedom of Information Act requests, highlighted the sheer scope and volume of the transfers, which ranged from the potentially worrisome to the bizarre.

Investigative journalism collective Muckrock, which crowdsources FOIA requests, eventually published full lists of the equipment deliveries it had obtained from DLA, which you can find here. DLA itself began releasing additional information proactively. Those tables, which showed transfers of armored vehicles, aircraft, weapons, and more to law enforcement entities ranging from state police to offices on college campuses and school districts, as well as the responses to other requests for new information prompted demands for investigations into how the program was vetting requests.

According to DLA’s website, between 1997 and 2016, the agency facilitated the transfer of more than $6 billion in surplus military equipment, ranging from everything from mine-resistant trucks and rifles to musical instruments and sporting equipment – no, really. In 2014 alone, law enforcement agencies got nearly $1 billion in gear.

The main argument against the Obama restrictions, as espoused by FOP and other law enforcement advocacy and lobby organizations, was that they prevented the transfer of potentially life-saving equipment to police departments and other law enforcement groups that would be unable to otherwise afford it. Military-style vehicles in particular might better protect officers in extreme emergencies. In its report, The Associated Press noted that an armored truck had played an important role in response to a domestic terror attack in San Bernadino, California in December 2015.

“It’s an important program,” Representative Austin Scott, a Georgia Republican, said in July 2017, according to The Washington Times. “I happen to know a sheriff’s deputy fairly well that stepped out of a Bear Cat [armored truck], and as he stepped out of it, a buckshot hit the window, and had he been in a normal squad car, he wouldn’t be with us today.”

The counter-argument is that military-style equipment distance police departments, who are supposed to protect and serve, from the communities they work in and make them increasingly inclined to use extreme force. Critics of things like the 1033 program say there is evidence that once law enforcement agencies have something, they’re more likely to find opportunities to use it. If it’s a weapon or an armored vehicle, they’d less likely to choose options that might de-escalate a situation and prevent the need for a violent resolution.

“We’ve seen how militarized gear can sometimes give people a feeling like there’s an occupying force as opposed to a force that’s part of the community that’s protecting them and serving them,” Obama himself said in a speech in May 2015. “It can alienate and intimidate local residents and send the wrong message.”

The change in the restrictions seems unlikely, however, to get at the real and continuing problems of how DLA vets requesters and assesses their needs. These issues continue to be more worrisome than the exact type of equipment it doles out to police, much of which seems to have been handed over with little oversight on either end.

“That was one of those things in the old days you got it because you thought it was cool,” Lynwood Yates, police chief in the town of Morven, Georgia, had told The Associated Press

back in 2013 about his decision to request bayonets through the 1033 Program. “Then, after you get it, you’re like, ‘What the hell am I going to do with this?’”

I discovered a similar situation when I tracked down how Black River Technical College, a small technical college in Arkansas with approximately 2,500 students, had gotten its hands on an ex-U.S. Army C-23 Sherpa light utility aircraft through the process in 2014. The school has a law enforcement academy that includes an aviation program.

Steve Shults, the director of Black River’s Law Enforcement Training Academy, wrote a memo less than 100 words long asking for the plane. According to DLA’s records, he only sent that letter in six months after the C-23 touched down a Black River.

Another two C-23s went to South Carolina’s Richland County Sheriff’s Department, after which they were improperly exchanged with a private aviation firm for two other aircraft, touching off a serious legal dispute with the federal government in 2015. Technically, the items DLA distributes under the 1033 Program remain U.S. military property that it can ask for back at any time.

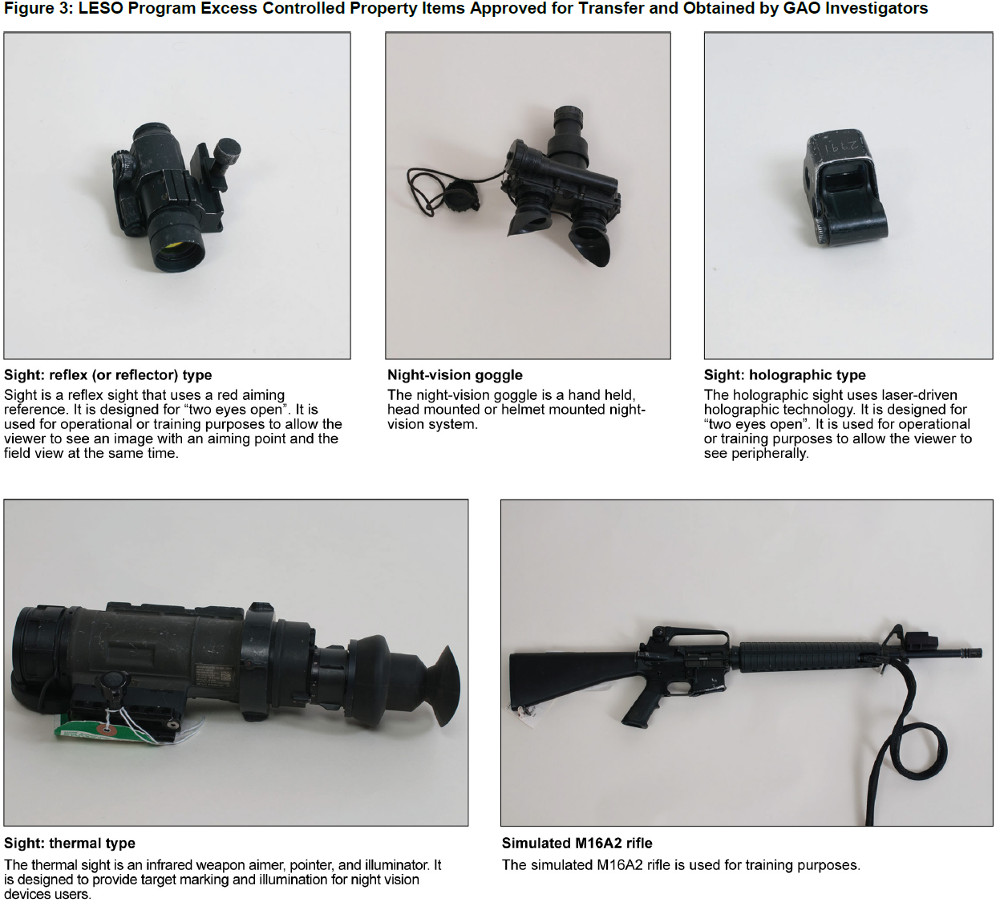

Even after the new restrictions went into effect, there were still serious concerns about how DLA manages the program. In July 2017, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a damning report explaining how it had set up an entirely fake law enforcement agency and obtained approximately $1.2 million in controlled items, including night-vision goggles and simulated rifles and explosives.

“DLA personnel [are] not routinely requesting and verifying identification of individuals picking up controlled property or verifying the quantity of approved items prior to transfer,” the congressional watchdog found. “Further, GAO found that DLA has not conducted a fraud risk assessment on the LESO [Law Enforcement Support Office] program, including the application process.”

The Pentagon concurred with all of GAO’s recommendations, which called for strengthening controls and accounting processes related to the 1033 Program. DLA estimated it would complete a full fraud risk assessment and implement a strategy to mitigate any problems it identifies by April 1, 2018. The agency also said it had already put into place new procedures for reviewing law enforcement agencies and their requests.

These new assurances are unlikely to sway critics of the 1033 Program given that DLA already had a mandate to improve these controls for over a year. The ranking Democrat on the House Armed services Committee, Adam Smith from Washington State, along with a colleague, Madeleine Bordallo, a Democrat representing Guam, had already called for a suspension of controlled equipment transfers after the GAO’s report.

It seems likely that Trump’s executive order with spur even more debate in Congress over the future of the 1033 Program. In the meantime, the more than 8,000 law enforcement agencies enrolled will once again be able to ask for tracked vehicles, bayonets, and grenade launchers.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com