In a week where it had already awarded major contracts for new work on replacing its nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) stockpile, the U.S. Air Force has announced two more major deals regarding the Long Range Stand Off (LRSO) nuclear-tipped cruise missile. There is an ongoing debate about whether the weapon is redundant, overly expensive, or increases the risk of a dangerous miscalculation, but it may offer a number of benefits, especially if the Pentagon’s latest nuclear posture review actively considers eliminating a leg of U.S. military’s Nuclear Triad.

Late on Aug. 23, 2017, the Air Force revealed the new contract awards to Lockheed Martin and Raytheon to continue design work on their respective LRSO designs. Both deals were valued at an even $900 million. The service rejected at bid from Boeing and it is possible that Northrop Grumman may have unsuccessfully submitted an entry, as well. These two firms had just beaten out Lockheed Martin and Raytheon to proceed with work on the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) ICBM replacement program.

“The LRSO will be a reliable, long-ranging and survivable weapon system and an absolutely essential element of the nuclear triad,” U.S. Air Force General Robin Rand, commander of Air Force Global Strike Command, had told members of Congress in May 2017. “The LRSO missile will ensure the bomber force continues to hold high-value targets at risk in an evolving threat environment, including targets deep within an area-denied environment.”

So far, the Air Force has released little information about its LRSO program’s basic requirements or the proposed designs. Contractors have been equally tight lipped about their proposals and Raytheon has even declined to issue any official statement regarding its newly won contract.

The most anyone seems willing to say is that the new design will be able to penetrate through even the most heavily defended target areas worldwide. As such it seems almost certain that the LRSO will be a low-observable design, but the Air Force has refused to confirm or deny if it will have subsonic, supersonic, or even hypersonic performance capabilities.

The new cruise missile will replace the existing nuclear and conventionally armed AGM-86 Air Launched Cruise Missiles (ALCM). The subsonic AGM-86B carries a W80-1 thermonuclear warhead, while the AGM-86C and D have high explosive and bunker-busting payloads, respectively.

The W80 series of warheads have a so-called “variable yield” and Air Force personnel can set it to explode with the force of between 5 and 150 kilotons of TNT. The LRSO will also use the W80-1, as well as have the option to carry conventional warheads for non-nuclear missions. As such, it is a dual role weapon system that can significantly expand the long-range conventional strike options for the USAF.

Boeing designed and built the AGM-86 family and the nuclear B model first entered service in 1981. It’s been a core component of the U.S. military’s nuclear deterrence capabilities since then. The Air Force wants to have the new LRSO missile ready to go by 2030, when it expects the existing ALCMs will reach the end of their service lives.

The service’s present plan is to make a final choice between the Lockheed Martin and Raytheon designs sometime between 2021 and 2022. The Air Force’s iconic B-52H BUFFs, B-2 Spirit stealth bombers, and the up-coming B-21 Raider will all be able to carry the new missile.

“This weapon will modernize the air-based leg of the nuclear triad,” Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson said in a statement. “Deterrence works if our adversaries know that we can hold at risk things they value. This weapon will enhance our ability to do so, and we must modernize it cost-effectively.”

But these assertions are clearly a response to wide-spread criticism of the project from both independent analysts and members of Congress. The main complaints are that LRSO provides a redundant deterrent capability, could potentially make it easier for the United States to accidentally find itself in the middle of a catastrophic nuclear exchange, and is simply too expensive.

It’s also important to remember that the existing AGM-86B missiles are one of the Air Force’s two remaining air-launched nuclear weapons, with the other being the B61 gravity bomb. The U.S. military, in cooperation with the Department of Energy, is separately working on an improved version of that weapon, known as the B61 Mod 12 or B61-12, which will feature a GPS guidance tail kit similar in concept to the conventional Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) family.

Critics suggest that since the B-2 or B-21 has the ability to sneak past advanced air defenses carrying a B61 nuclear bomb there’s no need for them to carry a stealth cruise missile. The main point of a long-range stand-off capability is to keep the launch platform away from these defenses in the first place.

The argument continues that though the decidedly non-stealthy B-52 would need the protection afforded by the LRSO, it will be on its way out by the time the missile is ready anyways. As it stands now, the BUFF is the only aircraft that can carry AGM-86 and this is the only nuclear weapon the aircraft can carry at all.

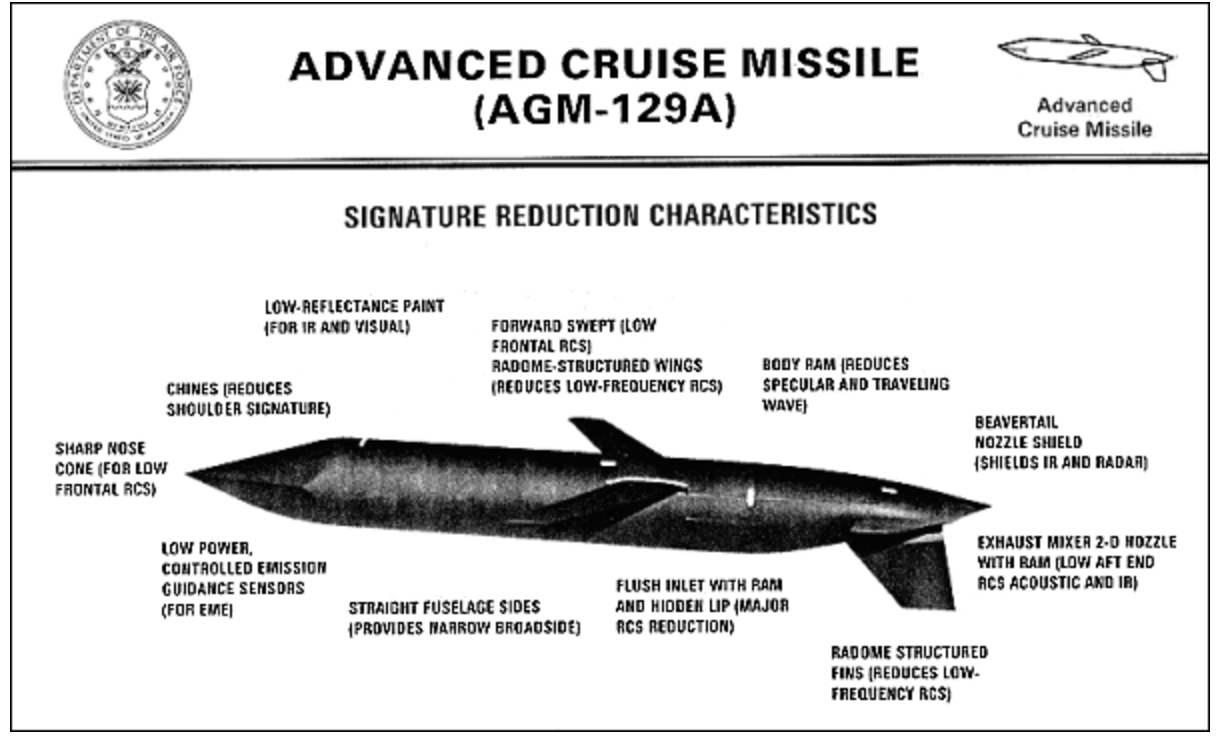

Those who oppose the LRSO note that the Air Force did have a stealthy stand-off weapon, the AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missile, but retired it in 2012. However, this decision was driven in large part by the need to reduce the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile in line by 2002 Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty, rather than the basics capabilities of the weapon. The Pentagon chose to scrap the AGM-129s rather than another system because they had experienced reliability issues and were more expensive to operate compared to the older AGM-86s.

These arguments also dismiss the reality that any missile-armed bomber could hit multiple targets faster than a bomb-carrying aircraft. At present, each B-52H can lug as many as 20 AGM-86s at a time, spread between racks under the wings and a rotary launcher in the bomb bay.

The contention is that if the target is truly time-sensitive, an IBCM or a submarine-launched ballistic missile would be a better choice to destroy it. As we at The War Zone explained in detail in our discussion of the potential game-changing nature of hypersonic weapons, this isn’t really the case, as ballistic weapons follow largely predicable trajectories and can have difficulties hitting small or otherwise complex targets.

In arguing the need for an ICBM replacement, the Air Force has itself alluded to a future full of ballistic missile defenses or other obstacles that could potentially reduce the capability of that class of weapons in a deterrent scenario. “The Minuteman III [ICBM] will have a difficult time surviving in the active anti-access, area denial environment that we will be dealing with in the 2030 and beyond time period,” General Rand informed Congress during a hearing in March 2016.

Bombers offer a more flexible option over ballistic missiles, as well, since they can stay on alert near a target area for an extended period, offering a visible deterrent without necessarily having to even fire a weapon. The time it takes to get them into position can be beneficial, too, since it gives commanders additional time to respond to a change in the situations and recall them before they release a weapon. And compared to a rocket motor igniting, bombers present a far smaller significant infrared signature, which could allow them to avoid detection by many space-based early warning systems.

As networked anti-aircraft weapons and radars, as well as fighter jets and airborne sensors, continue to improve, stealth may not guarantee safety, either. In a deterrence situation, the U.S. military might not have time to soften up an enemy’s defenses so a B-2 or B-21 would be able to slip through completely unmolested.

On top of that, there’s always the possibility the B-21 will not be ready on time and there is no plan for them to immediately replace the B-52 entirely in the nuclear deterrence mission by 2030. The Air Force only hopes the Raider will reach initial operating capability at that time and expects to buy between 80 and 100 examples at minimum.

If the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program and the costs of operating the existing B-2 fleet are any indicators, the new Raider could be an immensely complicated and expensive endeavor, and that’s not even touching the potential political issues. Based on these experiences, though, the Air Force has created a development concept for the B-21 specifically to at least try and prevent debilitating technical delays.

At the same time, in combination with a re-engine program, the remaining 58 BUFFs could easily stay in service through 2050. Without an improved stand-off nuclear weapon, the Air Force would be forced to relegate them to entirely non-nuclear missions. In May 2017, the Federation of American scientists discovered that the U.S. military had already quietly ended the BUFF’s B61-dropping mission in the face of the plane’s increasing vulnerability to enemy air defenses.

Of course, there is a reasonable question of whether the Air Force, which is already committed to a number of other modernization projects, including Nuclear Triad-related programs like the B-21 and new IBCMs, can afford the LRSO. The complete plan to overhaul America’s Nuclear Triad, which President Barack Obama initiated in his second term, could ultimately set taxpayers back $1 trillion.

LRSO has an estimated total price tag of around $20 billion. Critics say that it would be more logical to funnel those funds into other programs, including conventional-only stand-off weapons, or simply cut it out of the defense budget entirely.

But much of the redundancy and cost debate assumes in large part that the Pentagon will continue with its existing Nuclear Triad concept for the foreseeable future. As we’ve noted at The War Zone before, this is not necessarily a given.

There could be significant benefits in switching to a Nuclear Dyad instead, especially when taking into account the potential capabilities of the LRSO. When described as an alternative rather than a supplement to other weapons, such as ICBMs, a nuclear- and conventionally-armed cruise missile does begin to present a differently useful and cost-effective option.

The Ground Based Strategic Deterrent program could cost five times more than the LRSO project and would only have one real use – an apocalyptic doomsday mission. In fact, those missiles are as much of a strategic sponge for enemy missiles than anything else. If the Pentagon decided to recommend ditching the siloed missiles for good, it could fundamentally change the nature of the discussion about a new nuclear-capable cruise missile.

Still, none of this necessarily answers the serious question or whether or not a cruise missile, able to carry a nuclear or a conventional warhead without any visible difference in its appearance, presented a potential for miscalculation on the part of America’s enemies. The common scenario that independent analysts put forward is one where an enemy mistakes a conventional attack for a nuclear first strike.

This has been a long-running concern and remains a major question when it comes to American deterrence options, which may or may not have both conventional and nuclear components. The War Zone, thanks to documents obtained via The Freedom of Information Act, has already been able to take a closer look into these potential issues here.

That being said, the U.S. military has and continues to employ conventional cruise missiles on multiple occasions in unannounced strikes without issue. More specifically, the Air Force has fired conventional AGM-86C and D missiles during operations in both the Balkans and Iraq in the 1990s without triggering a doomsday scenario.

It is possible that a hypersonic LRSO could add an entirely new dimension to the equation, since opponents would have less time to try and determine the true nature of a strike. In addition, there is a tangential concern that American commanders might be more inclined to recommend using the the fast-flying missile, believing they could conduct a “surgical first strike” without giving the enemy time to react regardless of the payload.

There is already a fear that Russia has already adopted a similar attitude, thinking it might be able to use a small nuclear strike to halt a conflict on its terms without the threat of world-ending escalation. However, it seems that at least some the U.S. military have opposed this notion of “escalating to de-escalate.”

“Anyone who thinks that they can control escalation through the use of nuclear weapons is literally playing with fire,” then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work assured Congress in 2015, trying to allay those sorts of fears. “Escalation is escalation, and nuclear use would be the ultimate escalation.”

For the time being, though, in spite of vocal criticism, the Air Force is still pushing ahead with modernizing both of its legs of the Nuclear Triad. It may eventually have to decide whether its future deterrence capabilities lie with ICBMs or nuclear-armed cruise missiles.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com