The U.S. Air Force has already demonstrated the potential value of pairing its fifth generation F-22 Raptors with MC-130 special operations tankers. Now, the service is looking into build on that concept by putting a small package of the stealth fighters together with HC-130 search and rescue aircraft and HH-60G Pave Hawk helicopters.

Earlier in August 2017, personnel and aircraft from the Air Force’s 23rd Wing and 325th Fighter Wing teamed up for the exercise, nicknamed Stealth Guardian, at Moody Air Force Base in Georgia. The event evolved from an earlier version of the drill that the 23rd had conducted with other Raptors at Joint Base Langley-Eustis in Virginia three months earlier.

The 325th “saw an opportunity to integrate rapid raptor with rescue because of the capabilities of the HC-130Js,” according to an Air Force officer from the 23rd Wing’s 347th Rescue Group, who the service identified only as Major Tom. “Refining Rapid Raptor increases the Air Force’s flexibility to provide a strategic and tactical response at a moment’s notice,” an F-22 pilot from the 95th Fighter squadron, a Major Ryan, added.

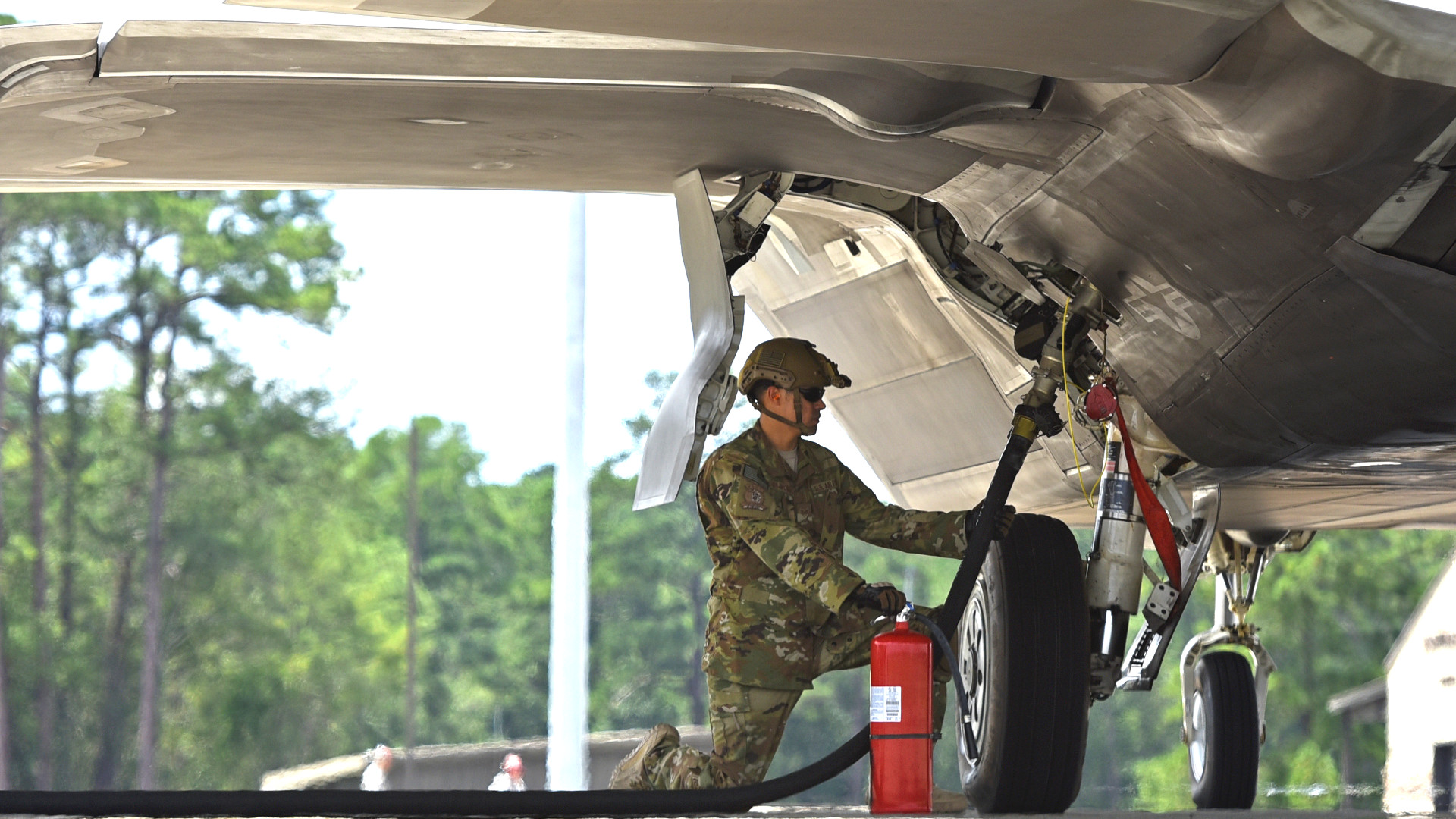

During the exercise, a HC-130J Combat King II from the 347th established a forward arming and refueling point (FARP) for the F-22s, as well as supported the HH-60Gs during simulated rescue missions. Crews identified the need for a new version of at least one part of the Rapid Raptor support package that can fit in any C-130 and the Air Force is already reportedly working on a solution.

Rapid Raptor is an operating concept the Air Force has been working on for some time now. It centers on the ability to quickly deploy at least four F-22s anywhere in the world and have them flying combat missions within 24 hours.

The central notion is that with an average of only 125 combat-ready Raptors on hand across the Air Force at any one time, it is simply impossible for the service to have them pre-positioned for all potential crises. In addition, it gives American commanders more options for dispersed operations, which could spread out the advantages of the stealth fighters, as well as other aircraft, across a broader area during an actual crisis, while also protecting those assets from enemy counter attacks.

In March 2017, following a similar exercise involving F-22s and MC-130J Commando II special operations aircraft, the War Zone’s Tyler Rogoway succinctly summed up the kind of high-threat environments that likely prompted the Air Force to develop the Rapid Raptor concept in the first place:

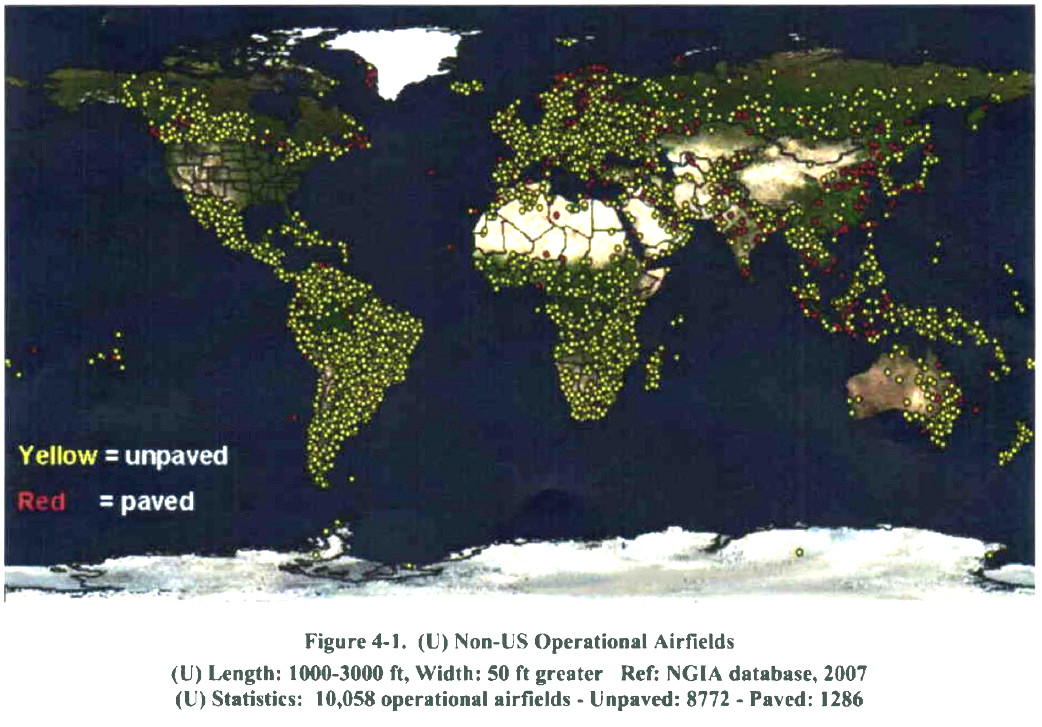

America’s fighter aircraft are born addicted to tanker gas. As enemy long-range defenses evolve, their limited combat radius is increasingly putting lumbering jet tankers and other support assets in harms way—a reality we have discussed in great detail before. Not just that, but considering that all nearby basing, as far as 1,500 miles away from the enemy’s mainland—and even farther in some cases—is vulnerable to cruise- and especially ballistic missile barrages, the idea that the USAF can just stack hundreds of fighters at their master air bases in a region is a dangerous notion indeed. Instead, during a time of war or of greatly increased tensions, American airpower should be dispersed in smaller numbers throughout a region, occupying austere airstrips on small islands that are not normally considered high-value targets.

Distributing air combat power throughout a huge theatre like the Pacific, and just getting tactical aircraft from larger bases thousands of miles away, to the target area and back will be no easy task. The USAF is beginning to come to terms with this and is tapping Air Force Special Operations Command for their expertise in setting up a gas station on the ground pretty much anywhere in the world in a matter of minutes.

This assessment, especially about the threat environment in the Pacific, has only become more pronounced since then, as tensions between the United States and North Korea have soared. Any conflict on the Korean Peninsula would require significant fifth generation aircraft, such as the F-22 to penetrate North Korea’s dense, if largely antiquated air defense network and initiate any attacks. More worrisome in the long term, China is still expanding its far more extensive anti-access/area denial capabilities further out into the region.

Deploying aircraft to dispersed locations quickly is just one part of the equation, too, made easier by extensive existing intelligence databases on possible airfields and landing zones that can support different types of aircraft and U.S. government agreements with allies to rapidly move into established “bare bases” or “cooperative security locations,” which have minimal, if any permanent American presence. Sustaining operations from these locations for any appreciable amount of time requires moving in the additional fuel and ordnance required for multiple sorties, as well as the other necessary communications and other gear to establish a functioning fighter jet operation.

According to the Air Force, a C-17 Globemaster III cargo aircraft typically carries the first load of this equipment during a Rapid Raptor deployment. As the service’s primary long-range airlifter, these planes are often in high demand. Training to use the smaller MC-130s and HC-130s could give the Air Force more options, as well as the potential ability to use move a Rapid Raptor package into a general area and then taking advantage of a network of smaller FARP closer to the target area.

The use of the HC-130J, which serves as both a transport and tanker for rescue forces, as well as the presence of the HH-60G Pave Hawk rescue helicopters, adds another dimension to these operations, as well. Rapid Raptor might be able to send F-22s where ever they might need to go, but it could also easily put pilots beyond the reach of help in the event of an accident over hostile territory or if the enemy does manage to shoot them down.

We’ve already seen some of what we might see in a combination Rapid Raptor and personnel recovery package in and around Syria. In 2015, the Air Force quietly deployed a personnel recovery task force with HC-130Js and HH-60Gs to a cooperative security location co-located with Turkey’s Diyarbakir Air Base, referred to as Site D.

This element, detached from the 332nd Air Expeditionary Wing in Kuwait, would rush in if F-22s flying from Al Dhafra Air Base in the United Arab Emirates, or any other coalition aircraft operating in the area, went down in Syria. With similar Air Force rescue units forward deployed near hot spots around the world, the service might be able to combined Rapid Raptor with these existing forces in the future, too.

Of course, there are also potential problems with combining decidedly non-stealthy aircraft like the C-130 with low-observable designs like the F-22. This only becomes more obvious when considering the idea of sending HC-130Js and HH-60Gs in to grab a downed Raptor pilot in a high-threat area protected by networked air defenses that an F-22 couldn’t survive in. How exactly combat search and rescue will work with F-35 and F-22 crews that will operate deep in defended territory remains a quiet but controversial topic within defense circles.

The War Zone has already highlighted the increasing need for stealthy tankers, and the Air Force has already begun to explore these ideas, as well as low-observable special operations transports and rescue helicopters for operations in denied areas. These would be ideal assets to pair with the Rapid Raptor concept.

As the Air Force continues to experiment with combinations of F-22s and C-130s, it may only prompt more interest in an entirely low-observable package. Perhaps in the future, we’ll see small groups of Raptors deploy for training exercises like Stealth Guardian along with similarly stealthy support aircraft.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com