There is no doubt about it, the U.S. military has let its short range air defense (SHORAD) capabilities wither on the vine. It seemed as if America’s air superiority advantage combined with 1990’s battle doctrine just didn’t require much in terms of ground forces being able to defend themselves from aerial attack, especially while on the move. Two wars in permissive aerial environments—Afghanistan and Iraq—didn’t help the SHORAD cause either, nor did the budget cuts of the current decade. But the tactical realities of the modern battlefield have changed, and it turns out that the Army, and the USMC for that matter, do need SHORAD capability and they need it bad.

The Pentagon’s combat doctrine has morphed drastically in recent years, with troops on the ground possibly being tasked with operating in contested environments where air superiority is not guaranteed. America’s once large air superiority margin has also shrunk, especially when it comes to expeditionary operations far from home. In addition, the battlefields American forces find themselves on today are so complex and crowded with competing forces, many of which have different agendas, that sanitizing large swathes of airspace isn’t an option—both tactically and geopolitically speaking.

Finally, and most importantly, the risk posed by weaponized unmanned aircraft has exploded. So far this threat has been presented largely by ISIS, a irregular force of fighters with varying levels of competence—much of which is poor—not a near peer state competitor with far higher professionalism and much greater resources.

The great laser gamble

As we have discussed in great depth before, the threat posed even by lowly hobby drones converted for nefarious purposes was clear long ago. The Pentagon as a whole largely eschewed the issue aside from executing some experimental testing and putting on a handful of obscure technological competitions to see how different countermeasures and tactics could be used to deal with these diminutive aerial threats. But above all else, small drones were fodder for the Pentagon’s experimental, costly, relatively low-powered and cumbersome solid-state lasers to roast out of the sky during tests. These systems weren’t powerful enough to take out incoming aircraft or missiles, but small fragile drones would give them a mission to teeth on. There is no doubt that eventually lasers would be the ideal weapon for taking on small drones—eventually.

In essence, the quiet denial that there was a real possibility US forces and their allies on the ground overseas could face this threat in the near term showed at best a lack of imagination on the part of DoD decision makers, especially considering some of us had been screaming about it for years. At worst it showed that those in charge at the Pentagon were willing to take on the risk posed by small weaponized drones for a period of time in hopes that the threat would not actually metastasize until easily deployable, compact, reliable and powerful solid-state lasers were ready for prime time.

That gamble failed miserably.

The battle for Mosul made it abundantly clear to the world that these relatively simple, commercially available and cheap weaponized drones weren’t a novelty. A mad search for countermeasures ensued as the headlines about their terrifying existence started hitting the mainstream press.

That search continues till this day.

Simply put, the enemy doesn’t act on the DoD’s timeline. In the end, the Defense Department had to finally accept the fact that the hobby-like drone threat had arrived, along with its wide ranging implications—not just for wars overseas but also for life here at home. This admission has spurred a cottage industry of sorts over the last year, that has included everything from jamming guns to exotic shotgun shells to sonic weapons—none of which are all that promising on their own.

Swatting down incoming mortars, rockets and artillery shells

The anti-small drone SHORAD requirement does share quite a bit of capability overlap with counter-rocket, artillery and mortar (C-RAM) defensive needs and capabilities. These traditional indirect fire weapons also pose an increasing threat to friendly forces operating on the ground in or near combat zones.

Today, C-RAM systems include everything from the Phalanx-based Centurion gun system to Israel’s Iron Dome surface-to-air interceptor system. The idea behind all these systems is to shoot down or neutralize these weapons as they careen through the air, before arriving at their target.

Under certain circumstances, C-RAM systems could also be used to shoot down low-flying helicopters, cruise missiles and aircraft. But you can’t shoot what you can’t see, and these defensive weapons usually have short sensor ranges, and overall low situational awareness. This gives operators less warning and less time to react, if any at all, to successfully engage threats that emerge farther off than rising mortars or short range artillery shells.

Like the small drone threat, lasers, with their indefinite magazine depth and fast as light engagement ability, are largely seen as the answer to the C-RAM issue, but they simply are not ready to take on such a threat, especially in a mobile battlefield environment.

Old threats made new

Dangers that require short range air defenses (SHORADs) are not just about small drones carrying improvised explosive devices or incoming artillery, they are also about larger drones, low flying manned helicopters and aircraft, and even cruise missiles.

Larger drones in particular will pose a serious danger to friendly forces in the future. Some of these have beyond line of sight control capabilities, and can drop or fire their own guided weapons at troops, vehicles, and material below.

Foreign-built remotely piloted aircraft (RPAs) are now proliferating at a fast pace, with China’s Predator-like Wing Loong being very popular, among many other international designs. Iran is also producing their own armed Shahed-129 RPAs, and these aircraft have popped up twice near a hot spot where American and allied troops are stationed in Syria, resulting in F-15E Strike Eagles swooping in and blasting them out of the sky.

Keeping combat air patrols overhead at all times to respond marauding drones is extremely expensive, and those aircraft are needed for other purposes. Not just that, but F-15s are not well designed to take out slow-flying drones with small radar and infrared signatures. Regardless, the shooting down of two Iranian drones, one of which had dropped weapons before being engaged by the Strike Eagles, was a signal that the days of having nearly a monopoly on drone warfare and full-scale air superiority are over for the US.

Traditional SHORAD threats, like low-flying fighter aircraft, helicopters and cruise missiles are also making a tactical resurgence. Once again, this is mainly due to the Pentagon’s new battle doctrine, the enemy’s investments in anti-access and area denial capabilities, and the erosion of America’s ability to guarantee air superiority, especially over a vast area.

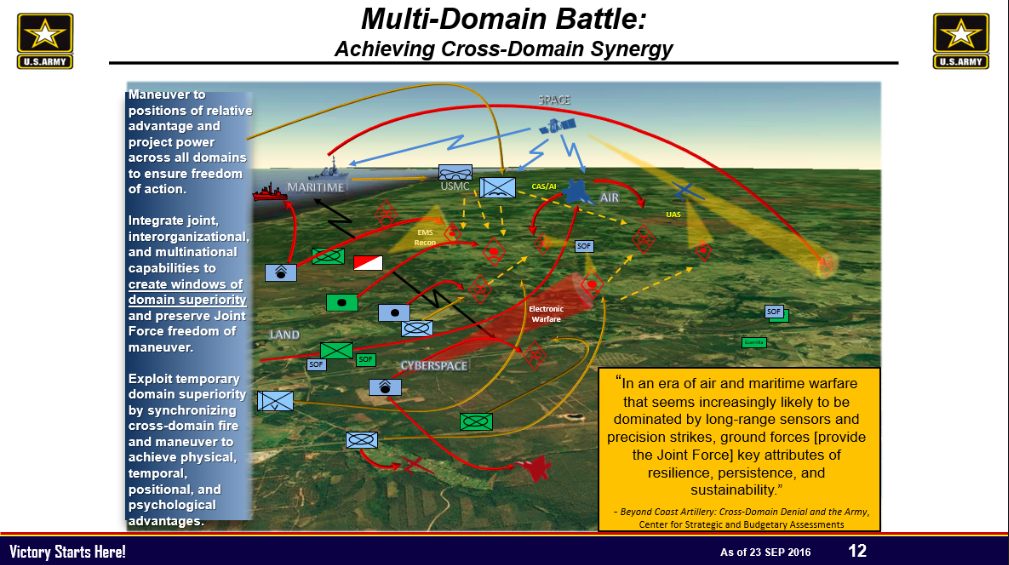

All this becomes especially important if the Pentagon were to execute on its multi-domain battle and maneuver warfare plans that it touts today in a contested and large combat environment like the Pacific. This will include thrusting allied troops into the enemy’s backyard, to areas where air superiority will not have been achieved and where sitting still on the ground for more than a few hours could result in losses of entire combat units. In other words, on the battlefields of tomorrow, Marines and Army infantry will have to be able to defend themselves from an aerial onslaught on multiple levels, at least sporadically—and do so on the move. Not just that, but no fighter aircraft or remotely launched long-range surface to air missile is going to take down small drones or rockets that threaten forward operating bases or roving columns of infantry.

A good way to visualize this is to imagine a war in Asia where there is a need to grab and hold islands that are inside China’s anti-access/area-denial “buffer zone.” These expeditionary operations that venture into contested territory will require the assets of all the services combined, including intelligence and communications gathered from space, and rapid and highly targeted strikes in the realm of cyberspace.

Part of this strategy also includes being able to move so fast that operations outpace the enemy’s decision cycle. Basically, you are gone before they can counter attack, or before that incoming attack has arrived. Otherwise you better have fortified an area fast enough that you can repel an attack on multiple levels.

But blitzkrieg operations over long distances, especially those separated by water, are very challenging even for the US military. Fighter aircraft will have their ranges stretched to the max even with tanker support, with very short periods of on station time over friendly forces. Naval surface forces may also have to standoff some distance. As such, ground units will need to be able to provide at least short range point air defense for themselves. Thus the need for a rapid and robust investment in SHORAD capabilities that can counter everything from drones to rockets to cruise missiles, otherwise the Pentagon needs to alter its land and amphibious warfare plans to be far less ambitious.

America’s dated and limited capacity SHORAD arsenal

Currently the US Army relies entirely on the FIM-92 Stinger missile slinging and .50 bullet caliber firing AN/TWQ-1 Avenger system. That wasn’t always the case. Systems like the Chaparral SAM system, M6 Linebacker, and the M163 Vulcan Air Defense System—the USMC also had the LAV-AD—once populated the Army’s mechanized ranks. Yet even the aging Avengers have decreased in numbers drastically over the years.

In 2004, there were 26 SHORAD battalions in the Army. Fast forward to today there are just nine. Of these nine, just two of them are active-duty units, the rest are in the National Guard. Now these remaining systems are in huge demand, with a deployment of 50 more Avengers to Europe being announced this week.

The Avenger system still mainly rides in the bed of a HUMVEE, but it can also be installed as a fixed emplacement, as it is on the Capital Mall as part of the integrated air defense system around Washington DC, and most notably, near the White House. The Avenger’s FIM-92 Stinger missile, which is best known for in its shoulder-fired man-portable air defense system (MANPADS) format, remains a fairly capable for short-range engagements, and it has just been certified to knock down drones. Avenger doesn’t carry its own radar, but can be linked into a nearby radar or a integrated air defense system for cueing. Even with its merits, far more capable systems exist. In fact, America’s potential enemies make arguably of the best SHORAD systems in the world.

Russia in particular has taken the SHORAD mission far more seriously than the US, namely because it has not had the luxury of nearly guaranteed air supremacy—or at least it never believed in that idea in the first place. Today, multiple Russian-built mobile point air defense systems are in production. Namely these include the Tunguska, Tor and especially the highly formidable Pantsir-S1. China has units like the LD-2000 30mm self propelled anti-aircraft gun, and the latest versions of the type also feature missiles. China’s HQ-7 is a clone of the French Crotale point defense SAM system. Other international systems, like the British Rapier and the French Roland are also soldiering on with different militaries around the globe.

The thing is that Avenger could be easily replaced, or at least drastically upgraded. Boeing has built and tested two variations of a new weapons turret that is capable of firing a larger array of weapons than just Stingers. Its primary air defense weapon would be the AIM-9X Sidewinder, which has a much farther reach than the Stinger, is more maneuverable, and has a better seeker system. Block 2 versions of the AIM-9X Sidewinder also feature lock on after launch capability and a data link, which means a radar can guide it to its target in any conditions, and it can fire without locking onto its target first. In fact, the launcher can be pointed in a totally different direction and the missile will still find its target if it is within its reach.

Boeing’s launcher can also sling Stinger, Javelin and Hellfire missiles. The Javelin can strike ground targets and helicopters, while the Hellfire can take out ground-based threats. This means the system can flex to a ground defense capability when there is no aerial threat. The launcher is also configured to accommodate a solid state laser in addiction to multiple missiles, which would be ideal for swatting down small hobby-like drones.

The first iteration of Boeing’s Avenger turret appeared in 2010, then again in 2014, although by then the system was much more compact and refined:

Boeing’s launcher is such a nice concept because it is modular in nature and new weapons can be added to it over time. Not just that, but the weapons it carries can be tailored depending on the threat. If aircraft, cruise missiles and drones are the threat, it can be outfitted with six AIM-9Xs and eventually a laser. If helicopters and ground vehicles are an equal threat it can be equipped with three Sidewinders and three Javelins. If there is no aerial threat aside from low-end unmanned aircraft, it can pack a full load of Hellfires and still have its laser available for countering small drones. A cannon can also be fitted, as seen on the first iteration.

Boeing is now showing off a slew of different vehicle-turret combinations that could be tailored to the Army and the Marine Corps’ unique needs. These include turret equipped Strykers, M-ATVs and Bradley fighting vehicles.

A laser SHORAD component with enough power to rapidly knock down incoming artillery is still a few years off, but vehicle mounted laser systems are already undergoing tests and they can swat down small drones even with lower powered lasers in many conditions. Still, pairing Boeing’s missile turret with a rapid-fire gun system for C-RAM vigilance, and tying them both to an advanced mobile radar unit, could represent the best of both worlds for now. At the very least it would give the guys on the ground a full spectrum and highly mobile SHORAD umbrella in the near term.

Centurion is a capable and proven system, but it isn’t designed specifically to operate on the move, so a different gun system may be best for this capability or the Centurion could possibly be modified. On the other hand, the Army could just live with the high cost exchange rate of shooting down $400 rockets with missiles that cost tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Army is also working on a road-mobile containerized launch system that can fire a variety of rounds. Think of it as a more complex, higher capacity system than Boeing’s updated Avenger turret launcher.

The so called Multi-Mission Launcher has been developed under the Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC) program. The launcher can spin 360 degrees and has 15 tubes for weapons, including Iron Dome’s Tamir interceptor, AIM-9X, FIM-92, AGM-114 and Miniature Hit-To-Kill projectiles, the former of which is being developed for the C-RAM mission.

It is a much larger system than Boeing’s new Avenger turret, but it could make up the higher-end of a high-low SHORAD mix. The system is built to primarily use a MPQ-64 Sentinel radar, which can be towed or can be vehicle mounted, but it also is intended to be able to leverage a varying network of sensors, which could include other high-mobility radar systems.

As we mentioned earlier, eventually, for short-range C-RAM and small drone engagements, directed energy weapons like lasers and microwave emitters will take over for gun, hit-to-kill, and missile systems. But a launcher for short to intermediate range defense against more robust aerial targets, like fighter aircraft, helicopters and cruise missiles, will still be needed. It could be possible that the Multi-Mission Launcher could even host Israel’s Stunner hit-to-kill missile, which can make the best use range-wise of a networked SHORAD installation with a powerful radar. This would fill help further fill the gap between the MIM-104 Patriot missile system and more traditional shorter-ranged point defense weapons.

Pushing high fidelity air defense sensors to the front

Having easy to deploy advanced sensors that can tie various SHORAD weapons platforms, or “shooters,” together is the “special sauce” at the heart of a modern SHORAD system that will keep troops safe from aerial bombardment of many types. In essence, the sensor that spots the target is just as important, if not more important, than the weapon that engages the target. Bringing broader and higher-fidelity airspace situational awareness right inside a convoy or small forward operating base would be game changing when it comes to the SHORAD mission.

Enter Northrop Grumman’s Highly Adaptable Multi-Mission Radar, or HAMMR for short, which is a refined version of the Ground Based Fighter Radar (GBFR) concept. This system is incredibly logical—take existing and proven components from active electronically scanned array (AESA) radars already flying on fighter aircraft and adapt them for the SHORAD mission. These systems are already built to be light, robust, and multi-role. By using existing hardware and even some software elements, large sums of money can be saved both in terms of research and development costs and via high-volume acquisition of common components. Money can also be saved when it comes to sustaining the systems and upgrading them over time.

HAMMR can be mounted on a vehicle, such as a HUMVEE, a trailer, or it can be arranged to be easily setup at a fixed position—like atop a building. Its powerful and super agile AESA array can detect everything from high-flying fighters, to incoming artillery rounds, to low flying helicopters, cruise missiles and even small drones. This information is data-linked to a command and control interface that is also in contact with various SHORAD weapons platforms nearby, creating a roving air defense network.

HAMMR, and other systems being developed like it, can operate in littoral, desert, jungle, or mountainous terrain. They can even work out at sea. This allows for maximum flexibility. For instance, if you want to setup a forward operating base in a town you can stick one of these on the roof of a building and have high-end aerial surveillance and targeting capabilities in a snap. Want to deploy a modular SHORAD system to a sea base? Plop one of these down on the deck and a missile launcher nearby. Need an air traffic control radar at a remote forward operating field that can also provide SHORAD capabilities? Drop one of these in.

The Marines are also working on their own highly mobile radar systems, one of which is proving to be quite capable, albeit more ungainly than HAMMR. This system is called the AN/TPS-80 Ground/Air Task Oriented Radar (G/ATOR) and it is in integration testing with other systems now. G/ATOR is a larger spinning AESA array that is trailer mounted and capable of providing short and medium range aerial surveillance and weapons cueing in a similar manner as HAMMR, albeit it remains unclear if C-RAM will eventually be part of its menu of capabilities.

This highly mobile but powerful new class of road-mobile radar systems can also feed information via data link to aircraft in the air and to other far more advanced missile batteries dozens, or even hundreds of miles away. Using net-centric cooperative-like engagement technology, a HAMMR or G/ATOR radar may pick up an enemy aircraft well beyond its SHORAD weapons’ reach. This information is streamed via data link to an Aegis equipped destroyer floating 75 miles away. The ship immediately fires off one of its SM-2 or SM-6 missiles to knock it out of the sky, saving the forward deployed troops and their SHORAD systems a close encounter. Fighter aircraft could also make similar cooperative engagements. So these systems not only facilitate the SHORAD mission, they also put persistent aerial surveillance forward, at, or beyond the front lines, and other friendly assets can exploit the information they gather. Even nearby forward air controllers can use these radars’ data to build a more accurate “picture” of the airspace around them, which will help for organizing close air support and precision fires.

In the end, the Pentagon’s slowly materializing SHORAD solution, which they call “Maneuver SHORAD,” will feature a cocktail of technologies, sensors and weapons platforms, tied together via a common data link and command and control apparatus. But it is also critical that these systems retain their ability to operate independently if need be, with radar and weapons platforms connected directly to one another in a traditional sense. This is especially important in an age of growing cyber and electronic warfare threats. This way, even if communications fail, especially those that require over-the-horizon connectivity, the system will still be able to provide immediate protection for nearby troops and their gear.

.

Better late than never

It’s better late than never when it comes to the Pentagon’s seemingly sudden rush for SHORAD capabilities, and none of it comes cheap. The missiles and interceptors used by higher-end systems alone will end up being among the most expensive investments when it comes to building up and sustaining a multi-layered and mobile SHORAD umbrella. But a scalable, flexible, and networked SHORAD concept should now be deemed a critical, high-priority capability if the Pentagon intends to fight the way it says it wants to in the future. Without it, thousands of lives and billions worth of equipment would be put at much greater risk during a time of war.

Funding is always a hurdle for any military capability, especially less glamorous ones like SHORAD, but why build a better tank or armored fighting vehicle at great cost if those systems will just be vulnerable to aerial attack? As such, the Army and the USMC need to make SHORAD a top priority and by most indications that is beginning to happen.

Fielding an Avenger upgrade/replacement with a highly mobile and more versatile system, along with a radar to make the most out of it, seems like the best first step. A basic self propelled gun system capable of C-RAM tasks would also be logical. A second phase could include building out a larger more robust air defense layer around systems like the Multi-Mission Launcher and its associated radar systems, with an eye on eventually turning over C-RAM duties to lasers and keeping the launchers and their expensive missiles for higher-end engagements.

SHORAD comes home

The thing is, lower-end SHORAD systems are also needed here at home, something we predicted years ago. The idea that small hobby drones can be fashioned into improvised weapons is not a concept that has boundaries, and a few hundred dollar drone could take out a VIP in transit or even a top of the line fighter jet sitting on the ground.

Just this week, it was announced that the Pentagon has cleared its base commanders to down any threatening drone operating near high value assets or critical military infrastructure. This comes after a drone got dangerously close to F-22 Raptor’s parked on the flightline at Langley AFB.

Speaking to the Air Force Association at a breakfast earlier in the month, Air Combat Command head honcho James Homes stated:

“One day last week I had two small UASs that were interfering with operations… At one base, the gate guard watched one fly over the top of the gate check, tracked it while it flew over the flight line for a little while, and then flew back out and left, and I have no authority given to me by the government to deal with that.”

He went on to describe another incident that happened that same day, this time a near collision while an F-22 was landing on the base. Similar concerns over drones operating near nuclear power facilities and other sensitive infrastructure have been well established.

The reality is that although the DoD’s proclamation allowing base commanders to order the downing of small drones may sound like a powerful move, base security personnel would be nearly powerless in actually executing such a order. The idea that an MP would start firing 5.56 rounds into the air at a tiny drone is unthinkable. That may be ok in a war zone like Mosul, but not at a base in a suburban area. Those rounds travel miles while still packing enough energy to be deadly. Simply put, nobody trained in small arms is going to open fire on something without knowing what’s beyond their intended target.

Other battlefield innovations, like the aforementioned radio frequency jamming “guns” and exotic “drone net” ammunition, maybe even shadowy electromagnetic and microwave pulse weapons, could potentially neutralize a malicious drone—but only if that drone is spotted visually first, and those armed with such systems are quick enough to react to it. Really, a whole slew of other variables make these countermeasures rickety at best. Not to mention suddenly executing jamming or microwave pulse operations at an airport is not really a good idea.

But once again, the key to having any chance of defending a particular site or asset from small drone attack is detecting the drone early on, before it is nearly overhead. Radar systems like HAMMR are one possibility, and other smaller, more rudimentary mobile radar systems have already been developed for this mission—some of which are fielded today, like Israel’s Drone Guard.

Laser weapons will be the best solution for taking down these types of drones even in domestic environments. But being able to reliably differentiate between friend and foe is key to seeing them deployed operationally, as is providing enough automated situational awareness so that the laser does not inadvertently strike any other aircraft passing in its beam’s path. Near and at airports these factors become even more crucial. Once again, the benefit here goes to a system like HAMMR that can paint a bigger situational picture of nearby airspace, and deconflict potential friendly fire incidents automatically. This can include stopping the beam from firing intermittently or not engaging the target at all if it poses a threat to aviation, human life or important infrastructure.

AESA radars themselves may have a latent ability to use their high powered and highly focused RF beams to damage small drones’ delicate electronics, or disrupt their two-way communications, especially at close range. With this capability in mind, a modular domestic SHORAD system could include a HAMMR like radar, and a laser turret with an infrared camera attached for target identification. The radar would first detect, classify and track the target. Once it is deemed potentially hostile, it can attempt to jam or disable it using electronic warfare means. If that doesn’t work it can then provide a laser firing solution that doesn’t affect nearby infrastructure or other aircraft that may pass in the beam’s path.

Small hobby drones can also be detected by the signals they send back to their users via electronic surveillance measures. But this technology may be better used to help with early warning and detection of an unmanned threat than providing fine telemetry for a laser or microwave emitter.

The coming swarm

Still, none of this confronts what is an inevitable evolution of the small drone threat—drone swarms. The enemy, either operating from the air or from the ground, will eventually be able to unleash dozens or even hundreds of small drones armed with explosive charges to fly downrange short distances and attack ground units and their material like bees. The Pentagon is already testing such a capability, and a simpler version of it could likely be realized by adapting off the shelf systems.

Being networked together, and being autonomous in nature after being loaded with a target area location, along with other mission parameters, these swarms will be extremely hard to defend against using even the best SHORAD systems in development today. It’s the saturation nature of the attack, the size of the attackers, and the fact that they work as a coordinated swarm, employing dynamic tactics to see as many in their company survive long enough to make their suicidal attack, that make them so deadly. They could even drop micro-munitions and be reused for a later attack. Just the knowledge that such an attack is possible would be psychologically stressful and demoralizing for troops on the ground.

Similar swarming strikes could be unleashed behind the front lines as well, with hugely expensive and low density/high demand combat aircraft being especially vulnerable to this sort of tactic—something General James Holmes alluded to inadvertently while speaking to the Air Force Association, stating:

“Imagine a world where somebody flies a couple hundred of those and flies one down the intake of my F-22s with just a small weapon on it.”

Actually, it would be even easier to just strike the jets as they sit idle and vulnerable on the flight line. One swarm could see a whole squadron of tightly packed fighters destroyed without even having a chance to fight back.

Maybe wide-area electronic warfare could help counter such a threat, at least to some degree. But clearly the best defense of all is to not let the enemy get close enough to launch such an onslaught in the first place. But this is a tough proposition when it comes to defense from such an attack in friendly areas or behind the lines, where even the fastest fighter jets sit stationary on flightlines, the coordinates of which are readily available on Google Earth.

Although it may sound like a page out a science fiction novel, the only thing that could probably counter such a dense swarming attack on ground forces or a garrisoned force would be for those forces to have their own counter-swarm swarms at the ready. This would result in dozens or even hundreds of mini kamikaze dogfights in the sky—a life and death suicide struggle among diminutive hive-minded flying robots.

Suffice it to say the SHORAD challenges of the future will be robust and plentiful. But it’s time we start tackling today’s SHORAD challenges head-on so we can adapt quicker to those of tomorrow. Getting America’s military back in the SHORAD game in a serious way would be a good first step in the right direction.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com