Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Navy, or IRGCN, has made yet another unsafe approach toward a group American warships, during which the U.S. Navy says one of its patrol craft fired warning shots. The incident is the second of its type in as many months, but reflects Tehran’s ever present desire for greater influence in the region.

On July 25, 2017, one of the IRGCN’s three Naser-class boats, which the U.S. Navy describes variously as an auxiliary patrol vessel or a light personnel transport, had an “unsafe and unprofessional interaction” with American ships while they were conducting drills in the Persian Gulf, USNI News reported, citing an official statement. The participants in the U.S.-only exercise included the Ticonderoga-class guided missile cruiser USS Vella Gulf, the Cyclone-class patrol craft USS Thunderbolt, two unspecified U.S. Coast Guard cutters, and an unnamed U.S. Army logistics vessel. The Army has a number of General Frank S. Besson-class logistics support vessels, the service’s largest and most capable ships, as well as smaller support craft, forward deployed in the region.

Here is the full statement the U.S. Navy provided to USNI:

An Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps naval vessel conducted an unsafe and unprofessional interaction with a U.S. Navy ship during a coalition exercise in the international waters of the Arabian Gulf, July 25.

The Iranian vessel made a close approach to coastal patrol ship USS Thunderbolt (PC 12), getting within 150 yards. The Iranian vessel did not respond to repeated attempts to establish radio communications as it approached. Thunderbolt then fired warning flares and sounded the internationally recognized danger signal of five short blasts on the ship’s whistle, but the Iranian vessel continued inbound. As the Iranian vessel proceeded toward the U.S. ship, Thunderbolt again sounded five short blasts prior to firing warning shots in front of the Iranian vessel. After the warning shots were fired, the Iranian vessel halted its unsafe approach.

The Iranian vessel’s actions were not in accordance with the internationally recognized COLREGs “rules of the road” nor internationally recognized maritime customs, creating a risk for collision.

“COLREGs” refer to a set of formal “International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea,” which, as the Navy noted, outline who has right of way in international waters and other precautions to avoid accidents. You can see how dangerous the situation with the Naser-class boat – also written Nasser or Nassar – could have become in video USNI obtained seen above.

The Naser appeared to be lightly armed, but that did not necessarily mean it might not have been threatening. The core of the IRGCN’s fleet is a number of modified civilian craft with fixed machine guns and rocket launchers or able to carry teams armed with their own weapons, including automatic rifles and rocket propelled grenades. There is always the possibility they could act as mine layers or even suicide bombs in an actual conflict.

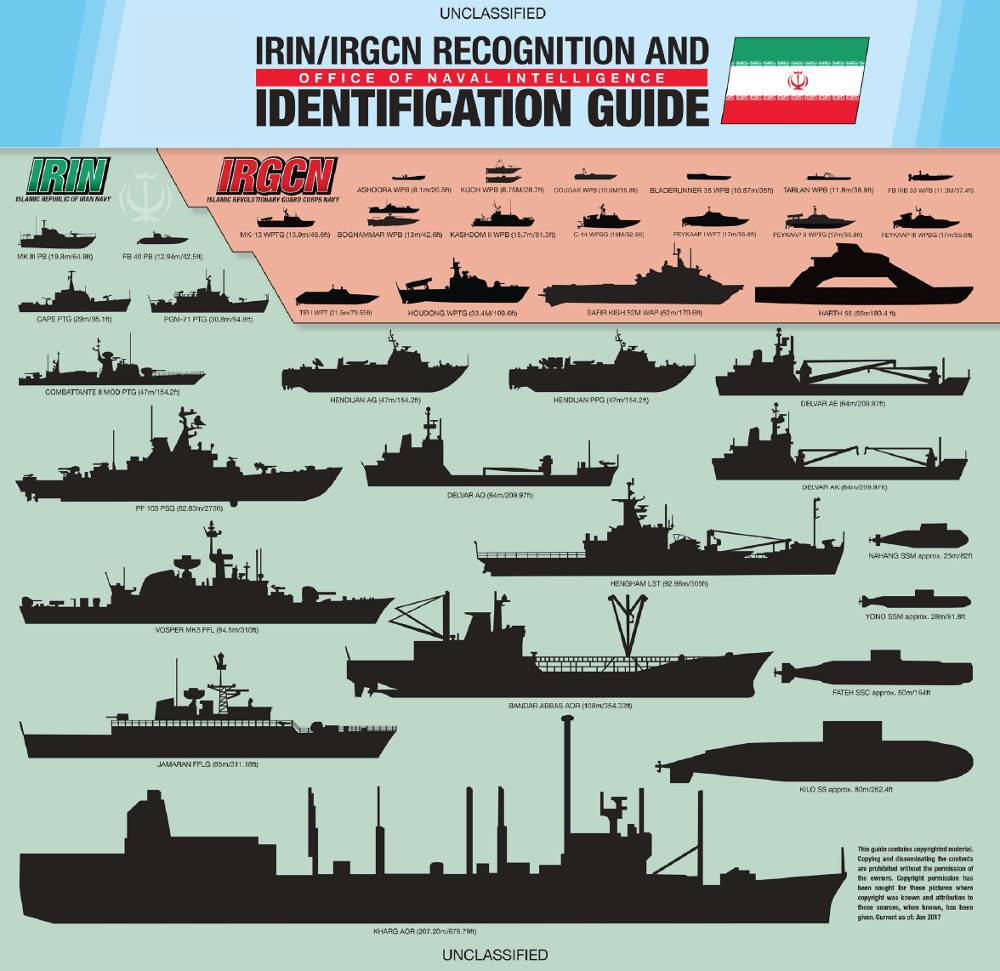

“The IRGCN believes it can overcome enemy defenses … by using different types of small and mobile weapons systems together, or by using its capabilities in unexpected ways to achieve tactical surprise,” the Office of Naval Intelligence wrote in an unclassified review of Iranian naval forces, which it released to the public earlier in 2017. “Driven by an asymmetric doctrine –based on speed, numbers, stealth, survivability, and lethality – the IRGCN focuses its naval acquisitions along four primary capabilities: fast attack craft, small boats, anti-ship cruise missiles, and mines.”

The IRGCN’s adoption of the Naser in the first place may have been response to a lack of alternatives international sanctions against Iran over its nuclear and ballistic missile programs. The Arvandan Shipbuilding Company, which generally specializes in light passenger ferries and other civilian craft, built the Nasers. In June 2017, Iranian Rear Admiral Abbas Zamini, Deputy Commander of the separate Iranian Navy, suggested his branch was also interested in using converted commercial ships as launching platforms for anti-ship missiles.

This is also hardly the first time IRGCN ships and other craft have harassed American warships in the Persian Gulf. Separate from the regular Iranian military and in charge of a host of industrial and other concerns, observers generally see the IRGC’s activities as a whole as reflecting the often hardline domestic and foreign policy objectives of the country’s Supreme Leader and other unelected clerics rather than its elected government. This includes a categorical opposition to American influence and military presence in the Middle East. However, given the Corps’ unique position in Iran, it is not always clear who actually controls their actions.

In June 2017, one of the IRGCN’s Thondor-class missile boats had come within 2,400 feet of the U.S. Navy’s amphibious assault ship USS Bataan, the escorting Arleigh Burke-class destroyer

USS Cole, and the supply ship USNS Washington Chambers. The Chinese-made Iranian vessel shined its searchlight and a laser light on the formation, as well as helicopters transferring goods from the Washington Chambers, in another unprofessional and potentially dangerous display.

In March 2017, an unspecified Revolutionary Guard Corps’ boat maneuvered in front of the spy ship USNS Invincible before coming to a complete stop in the larger ship’s path, which could have led to an accident. Two months before that, Arleigh Burke-class destroyer, the USS Mahan, fired three warning shots to chase away a flotilla of four IRGCN fast attack craft that appeared to be rushing toward the American ship as it transited the narrow Strait of Hormuz. There were more incidents in 2016, including at least one other involving a Naser-class boat. In each of these instances, the U.S. Navy made a public complain about the Iranian actions.

But while there is a certain routine nature to these incidents, and Iran has never followed through on threats to close off the Strait of Hormuz to foreign military ships in the past, the U.S. Navy has had reason to take these interactions especially seriously in the past year. In January 2016, IRGCN forces captured 10 American sailors and two Riverine Command Boats that had drifted into Iranian territorial waters near Farsi Island, touching off a tense international incident. One of the craft had suffered an engine breakdown and lost track of its position.

Though American officials quickly secured the release of the sailors and defused the situation, IRGC-linked media had already broadcast humiliating imagery of the American personnel and apparent formal apologizes for violating Iranian sovereignty. A subsequent U.S. Navy investigation found that the sailors and their superiors had been responsible for a series of failures that put them in the situation to begin with, but that Iran had violated a host of international norms by detaining rather than assisting the broken down ship.

It’s not just the United States that Iran has been sparring with in international waters, either. In June 2017, Saudi Arabia claimed it had captured a team of IRGCN commandos near the offshore Marjan oilfield in the Persian Gulf. Iran strenuously denied the Saudis had captures any of its forces or that they had been near the Saudi oil rigs to begin with while countering that the Royal Saudi Navy had actually fired on a pair Iranian fishing boats, killing an innocent civilian. The next month, Iran’s semi-official Fars News Agency reported the IRGC had captured a Saudi-flagged fishing boat trespassing in Iranian waters, with Saudi officials taking their turn to deny the incident had even occurred.

But critics of President Barack Obama and his administration pointed to a multi-lateral deal with Iran over that country’s controversial nuclear program as having enabled the IRGCN. Opponents of that arrangement, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), claim it has otherwise empowered Iranian authorities to continue pursuing destabilizing policies across the Middle East. Iran’s military is reportedly considering opening bases in Syria and Yemen to expand its physical footprint abroad.

This includes supporting Houthi rebels in Yemen who are fighting a Saudi Arabian-led coalition, propping up the brutal dictatorship of Bashar Al Assad in Syria directly and through proxies including the Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah and other militias – some of which have attacked American-supported forces in the country – and increasing military and economic cooperation with the government of Iraq. Iranian-backed groups have also been fighting ISIS alongside Iraqi government troops and on July 23, 2017, the two countries quietly signed a new agreement on military and counter-terrorism cooperation that has the potential to reduce American influence on Iraq’s security forces.

This has in turn pushed U.S. military officials to seek a role in the country even after the terrorist threat has subsided in order to counter Iran’s influence. President Donald Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia in May 2017 had a decidedly anti-Iranian tone to it, as well. The American leader has repeatedly called the JPCOA a “bad deal” and there are rumors he might try to renegotiate its terms, despite Iranian officials contending that this proposal would be a non-starter. In June 2017, he threatened Iran, along with Russia and Syria, over possible future chemical weapons attacks in Syria.

In July 2017, the Trump administration reluctantly admitted that the Iranian government was abiding by the terms of the Iran deal. However, criticizing the country’s separate and continued work on ballistic missiles and support for international terrorist organizations, this announcement came along with a raft of new sanctions against Iranian individuals and entities.

Of course, Iran’s continued push to assert itself throughout the Middle East hasn’t been without its own problems. The country’s support for the Assad regime has made it a target for ISIS, who launched a pair of unprecedented terrorist attacks in Tehran in June 2017. The attackers killed more than a dozen people and the entire affair threatened to drag Iran deeper into a still simmering regional crisis.

For its part, the IRGC pointedly blamed Saudi Arabia, which is accuses of supporting Sunni extremists like ISIS, as being ultimately responsible for the incident. It also put its ballistic missile capabilities on display afterwards in a major and heretofore unseen ballistic missile attack ostensibly against ISIS in Syria. However, it seemed clear that the strike also served as a show of force against Iran’s regional competitors, including the Saudis.

In light of this, the increasingly complex and confusing situation in Syria, Iran’s reported support for the Houthis, its long-standing rivalry with the Saudis, and continuing exchanges of tough talk with the U.S. government, it seems likely that the IRGCN will continue to harass American ships in the Persian Gulf for the foreseeable future as an easy way of showing its continued defiance against its international opponents. Unfortunately, these interactions will also continue to run the risk of a dangerous miscalculation that could turn them into a violent skirmish or even a larger conflict.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com