The U.S. Navy has revealed the latest details about what it expects from its already dumbed-down MQ-25 Stingray drone program. In a new twist, the service has downplayed an already limited reconnaissance requirement while expanding the scope of the proposed unmanned aircraft’s aerial tanking duties.

On July 19, 2017, the Navy sent out a draft request for proposals to four defense contractors – Boeing, General Atomics, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman – ahead of the service’s planned release of a formal notice sometime in the fall, according to USNI News. Notably, this document outlines just two so-called “key performance parameters,” or KPPs, for any proposed design.

“The system needs to be able to operate off of the aircraft carrier and integrate with all of the subsystems of the carrier,” U.S. Navy Captain Beau Duarte, the MQ-25 program manager, told USNI. “Sea-based tanker is the second KPP. It needs to be able to deliver a robust fuel offload at range to support an extension of the air wing and add flexibility of what’s available from a mission tanking perspective.”

It’s a testament to Pentagon bureaucracy that the Navy has to specify the first of these requirements at all. That the unmanned aircraft, previously known as the Carrier-Based Aerial-Refueling System (CBARS), would need to use existing carrier subsystems, such as catapults and arresting equipment, is a long-established given.

The second KPP, however, is a small, but significant change from how the service explained the drone’s planned missions when it applied for the MQ-25 designation in 2016. In that request, which the author previously obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request, the primary focus was on recovery rather than mission tanking.

Recovery tanking is a much more limited task involving an aerial refueling aircraft flying fixed orbits in close proximity to the carrier. The concept allows carrier fighters or strike aircraft to fly missions that take up much of their fuel, knowing that when they return they can take on additional gas and land safely.

Since the Navy’s carrier air wings do not presently have a dedicated tanker, Super Hornets have to fill this role using a detachable “buddy pod” store. This takes the aircraft away from their primary duties as a strike fighter. So, having the Stingray do this work would lead to “a substantial increase in mission capacity and can also extend the reach of existing [carrier strike group] capabilities,” according the MQ-25 designator request packet.

Only one MQ-25 in each complete “unmanned aerial system” – which would include multiple drones, an MD-5 ground control station, and other associated equipment – would be available for so-called mission tanking. Unlike recovery tanking, this mission profile has aerial refueling planes operating in orbits nearer to the target area.

To perform this job, the tanker would have to have a greater maximum range of its own and could expect to find itself closer to enemy defenses without the protective umbrella of the carrier and its escorts. At present, large U.S. Air Force KC-135 and KC-10 tankers perform the bulk of the U.S. military’s mission tanking across all the services.

The shift in focus from primarily recovery to mainly mission tanking could potentially lead manufacturers to develop significantly larger designs than they might’ve originally planned to submit. In line with the original focus on recovery tanking, both Boeing and Lockheed Martin have already released concept artwork showing nothing but what looked like the Navy’s existing buddy pods without any significant amount of the aircraft itself visible. Duarte confirmed to USNI that this piece of kit is part of the requirement, but that the rest is up to the manufacturer.

“We are saying that you do have to use the existing aerial refueling store that F/A-18s [and] S-3s have used – and that’s externally carried – and that’s to reduce development, cost and timeline and risk,” Duarte explained. “But how you configure the air vehicle to deliver that fuel is up to industry.”

Also, Duarte made no specific mention of the Navy’s earlier desire for the aircraft to still have limited intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities. This was a holdover requirement from the original strike and reconnaissance focused Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike (UCLASS) program.

In asking for the MQ-25 designation, the Navy specifically said that drones would be available for intelligence gathering missions when not providing tanking services. The requirements described an unmanned aircraft able to gather imagery, including full motion video, during the day or at night, as well as signals intelligence data. It would also have the necessary data links to transmit that information back to the carrier, to other ships or even submarines, other manned or unmanned aircraft, and troops on the ground.

We don’t know whether or not the Navy has decided to scrap the intelligence gathering mission entirely. “There are a number of key system attributes or other requirements lower than that that are subsequent to and are of lower importance and that will allow us to focus on those two key areas on tanking and carrier suitability and let those be the primary design drivers,” Duarte noted.

All of this seems to suggest the Navy may have decided to focus on tanking above all else, at least initially. This singular mission focus could help the service keep costs low and get the aircraft into service quickly. In April 2017, Boeing, General Atomics, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman each received more than $18 million to continue work on their MQ-25 designs, even though the final requirements were still in flux and it was unclear when any production aircraft might actually be combat ready. There is no estimated final price tag for the project as of yet.

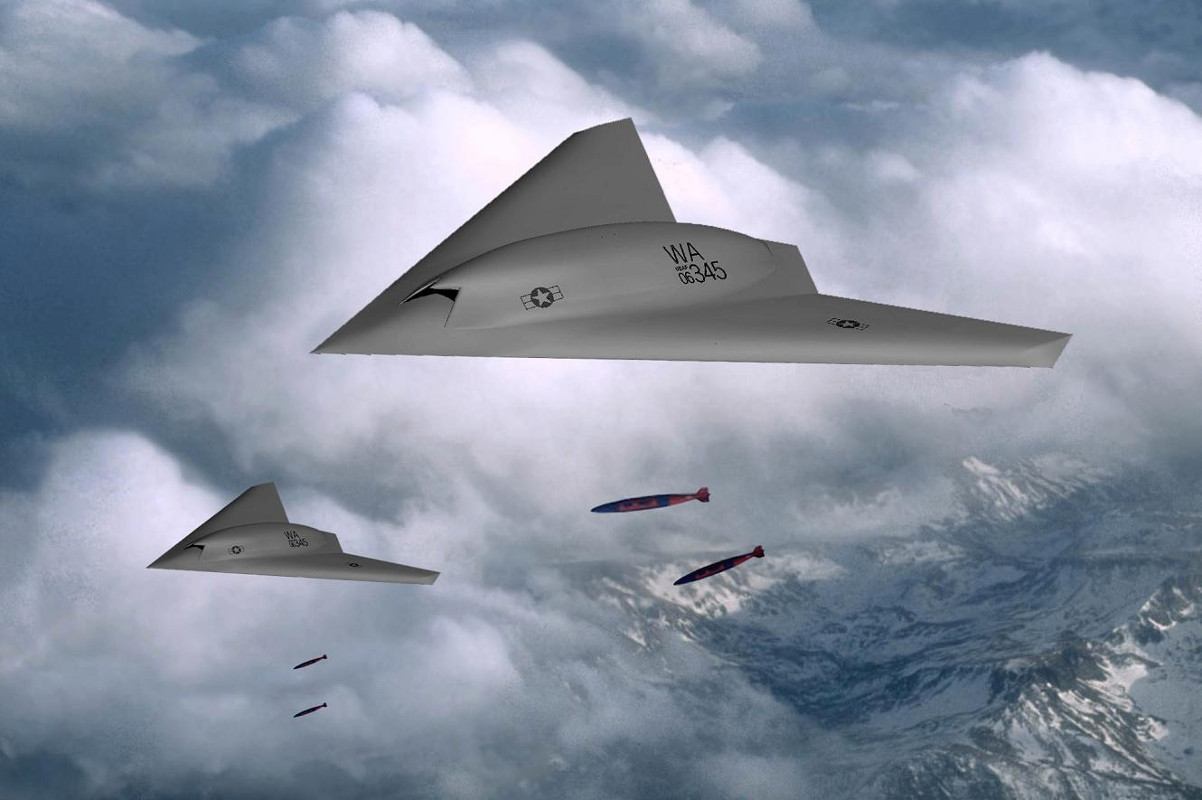

But billing the aircraft as nothing more than a pilotless gas station could limit the ability for the Navy to employ them for other tasks in the future. The original UCLASS designs – Boeing’s Phantom Ray, General Atomics’ Sea Avenger, Lockheed Martin’s Sea Ghost, and Northrop Grumman’s X-47C – were low-observable drones clearly intended for deep strike and intelligence gathering in so-called anti-access/area denial environments, or A2/AD, full of networked air defenses and hostile aircraft.

The shift in requirements to a tanker with secondary intelligence gathering capability already suggested manufacturers might rework their proposals around less costly non-stealthy designs. “From our viewpoint, the requirements, as they are currently unfolding, are going to require a new design from all of the competitors,” Rob Weiss, head of Lockheed’s Skunk Works advanced projects office, told USNI in March 2017.

If the Navy did decide it needed a deep strike unmanned combat air vehicle in the future, an aircraft that may ultimately become essential for operations in heavily defended areas, these new pilotless aircraft could be wholly unsuitable for the task. Whether they could perform the kind of secondary reconnaissance mission the Navy had originally envisioned is debatable with this new primary focus on longer range aerial refueling. A modular design that could accept additional mission equipment would necessarily be a substitute for a purpose-built low observable design.

Of course, there is always the possibility one or more of the four contractors could put forward a stealthy tanker design. There is growing evidence that aerial refuelers, manned or unmanned, are increasingly vulnerable in high threat environments in general. In May 2017, a Russian fighter jet intercepted and then did a barrel roll atop an Air Force KC-10 flying over Syria, underscoring this potential danger. But unless all of the competitors decide to go this route, anyone who does might be stuck making an offer that is significantly more expensive and less attractive as a result.

Still, in his interview with USNI, Duarte sought to downplay these concerns and the idea that there would be a need for all new aircraft concepts. “The program has been structured so there isn’t any new development. There’s no new science here,” he insisted.

That’s not really true, of course. Northrop Grumman’s X-47B demonstrator and its associated technological advancements had made clear the impressive potential of a carrier-based combat-capable drone as outlined in the original UCLASS program. Since then, the Navy, as well as the U.S. Air Force, has repeatedly declined to push ahead with UCAV concept for reasons that remain largely unclear.

In the case of the MQ-25 specifically, it could be that naval aviators saw the Stingray as a threat and have argued behind the scenes for reduced requirements. Maybe multiple branches feared the drone would eat into budgets for more F-35 Joint Strike Fighters or updated F/A-18 Super Hornets. We don’t know for sure, but it seems clear that the decision against a deep-penetrating, stealthy attacker in favor of a tanker was not done without careful consideration of one or more factors.

Whatever the case, it will be interesting to see how Boeing, General Atomics, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman ultimately interpret the Navy’s latest requirements.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com