It’s a truism that if a country’s military, no matter how big, cannot operate for a protracted period beyond its own boundaries, then it is little more than a territorial defense force. Since the end of the Cold War, the People’s Republic of China and its People’s Liberation Army have been hard at work to shake this perception of their capabilities and expand their presence around the world. Now, Chinese troops are on their way to the Horn of Africa to staff the country’s first permanent overseas base, which opens the door for deployments well beyond the continent.

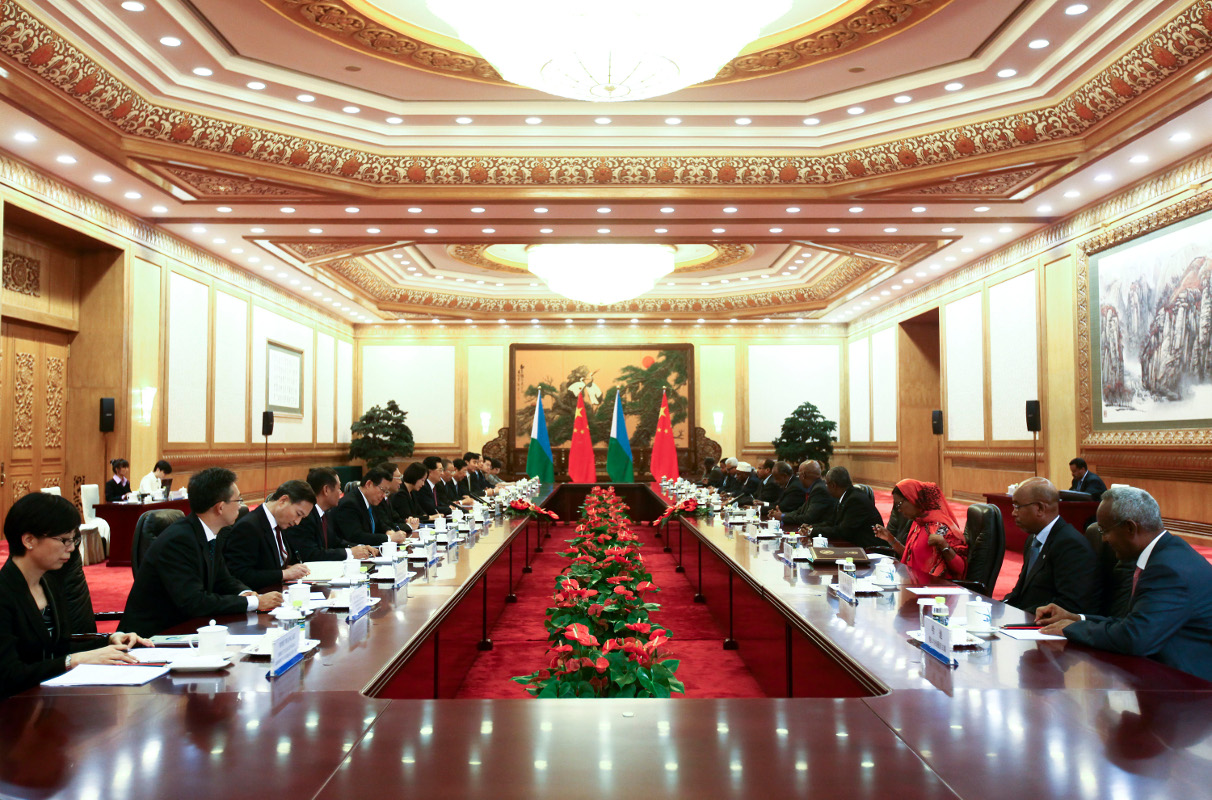

On July 12, 2017, Chinese state media outlet Xinhua reported that the first group of personnel and equipment was headed to the country’a new “support base” in the small East African country of Djibouti. China first announced the plan in 2015 and began building the facilities, situated in the capital Djibouti City, the following year.

“The support base will better serve Chinese troops when they escort ships in the Gulf of Aden and the waters off the Somali coast, perform humanitarian rescue, and carry out other international obligations,” Xinhua explained, citing statements by Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang. “Moreover, the base will be conducive to driving Djibouti’s economic and social development, and assist China’s contribution to peace and stability both in Africa and worldwide.”

Though it can undoubtedly fulfill these functions, on closer inspection the site looks in line with a larger trend on the part of the PLA to take a more active role internationally. The base provides Chinese Forces a key stepping stone for persistent and independent access to the Middle East, Europe, and beyond, regardless of their mission.

What is China’s plan?

The Chinese have been particularly sensitive about the new base and the contingent it would house, offering few specific details about the composition of either. In official remarks, neither Geng nor Vice Admiral Shen Jinlong, head of the PLA Navy (PLAN), provided any additional information. However, previous reports suggest that there will ultimately be approximately 1,000 Chinese military personnel in Djibouti.

Officially, the job of this contingent is “logistics support” for PLAN forces in the region. Chinese ships have deployed to the Gulf of Aden since 2008 to help protect commercial shipping against piracy and other dangers. Though its forces have not part of any of the other multi-national counter-piracy task forces in the region, China has conducted this mission unilaterally under the broad mandate of a number of U.N. Security Council resolutions.

“The support facility will be mainly used to provide rest and rehabilitation for the Chinese troops taking part in escort missions in the Gulf of Aden and waters off Somalia, U.N. peacekeeping and humanitarian rescue,” the Chinese Defense Ministry told The New York Times

in a written statement as recently as February 2017. But the choice of the word “mainly” may be a key caveat.

Fox News obtained unclassified satellite imagery from earlier in July 2017 that showed extensive construction at the base still underway. Most notably, there appear to be new aviation facilities that could ultimately support helicopters or unmanned aircraft. There are at least seven structures that look like hangars, connected by a 1,300 apron for planes to park, refuel, and rearm. In addition, there is another, central building that could serve as a control tower and command center.

The work is unfinished in the July 4, 2017 images and there are no aircraft present. However, the site looks large enough to accommodate China’s Wing Loong or Wing Loong II drones, which can carry both weapons and sensors and are roughly equivalent to the U.S. military’s MQ-1 Predator. With a reported range of over 2,400 miles, these pilotless planes would be able to fly armed surveillance missions throughout the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea, and even further out into the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean from the base. It would also allow over-land operations in East Africa, including South Sudan, where Chinese troops are part of a U.N.-backed international peacekeeping mission. From the base, helicopters could also ferry troops and supplies – and casualties and evacuees – back and forth from nearby ships.

The base’s potential to support broader expeditionary operations was on full display during the ceremony marking the departure of the first PLA contingent headed for Djibouti. Official pictures showed a two ship flotilla consisting of the Jingangshan, a Type 071 landing platform dock, and Donghaidao. This second ship, which the PLAN only commissioned in 2015, is semi-submersible logistics vessel displacing approximately 20,000 tons when fully loaded and is similar in concept to the U.S. Navy’s much larger Mobile Landing Platforms.

With this unusual looking design, these types of ships can carry over-sized cargo or act as floating sea bases in support of amphibious and other operations. In the past, the Chinese have showed off the ship, which first deployed in support of the country’s expanding presence in the South China Sea, acting as a mothership for a Zubr-class air-cushion landing craft. The ship is just one component of a larger expansion of the PLAN’s blue water capabilities, which notably includes work on multiple aircraft carriers and advanced surface warships that will be at the core of future carrier battle groups, as well as be able to perform independent operations.

What do the Chinese really want?

There is nothing to suggest that China’s ostensible reasons for wanting a permanent base in Djibouti aren’t true. Since the 1990s, Chinese military and police forces have become key components of the U.N.’s peacekeeping structure. As of 2015, the country had committed approximately 8,000 personnel to the international organization’s standby reserve, making up a fifth of the total force. The majority of these activities are in Africa. On top of that, China is an active

support of the African Union’s own peacekeeping missions, having pledging at least a $100 million to help maintain its own rapid response elements.

By December 2016, in addition to the deployment in South Sudan the country had troops with other U.N. missions in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Mali, and Sudan’s contested Darfur region. Other personnel had joined the U.N. contingent in Lebanon. The government in Beijing had become the largest contributor to these operations, on average, among the permanent members of the U.N. Security Council.

This makes perfect sense, since China has similarly increased economic ties across Africa, particularly in regards to resource extraction industries. Chinese workers dot the continent and China outright paid for the entire $200 million construction of the African Union’s new headquarters in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, which has been called “China’s gift to Africa.” Its powerful soft-power diplomacy that has helped ingratiate the country with regimes across the continent, though not always the local populace.

Though the United States is often accused of propping up African dictators, the totalitarian government in Beijing has far less interest in even broaching sensitive topics such as human rights abuses, with a long-standing official policy of not “meddling” in other countries’ affairs and demanding the same of others. This makes them a particularly attractive partner for repressive leaders. These include regimes that the U.S. and other western powers refuse to work with, such as the governments in Sudan and Eritrea. In the case of Djibouti itself, international monitors, independent humanitarian groups, and opposing political factions have accused President Ismaïl Omar Guelleh and his ruling People’s Rally for Progress party of rigging elections, suppressing political opposition, and jailing opponents on trumped up charges.

Chinese political and economic engagement in Africa has only reinforced the need for an outpost on the continent to support unilateral military missions in times of crisis. In 2011, as the regime of Libya’s long-time dictator Muammar Gaddafi collapsed, China suddenly had to find a way to help more than 35,000 of its nationals flee the country. In 2014, it repeatd the process, but had to call upon other countries, including Greece, to help. Authorities in Beijing facilitated a much smaller evacuation of some 600 individuals from Yemen as the small country on the Arabian Peninsula devolved into civil war four years later.

The simple act of sailing up and down the coast of Somalia hunting for pirates had already been logistically complicated for the PLAN. During those operations, “Chinese officers and men encountered difficulties in replenishing food and fuel, and Djibouti offered logistical support in multiple instances,” Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesman Geng had acknowledged in his July 2017 remarks.

China as an international military power

But these official missions are just one piece of the larger picture. Beyond regional security concerns, the facility in Djibouti can only help China obvious desire to expand its military presence well beyond its borders. The African country is strategically located near the Suez Canal, providing a stable, Chinese-controlled stop-over point for military fleets heading to Europe and beyond. Its especially well positioned to both protect the transport of Middle Eastern and African energy and mineral resources critical to China’s overall economic development, as well as provide storage space for the fuel and other supplies the PLA needs to conduct operations in Africa and Europe. Having these port facilities will be essential if the country wants to conduct far-flung carrier battle group operations. It seems almost guaranteed that once the base in fully operational the country’s first operational carrier, the Liaoning, and its escorts will make it a regular port of call.

The decision to establish the overseas base has lined up with dramatic cuts to the PLA’s ground forces, too. In 2015, the Chinese military trimmed 300,000 personnel from its total strength. Just one day before its troops set sail for Africa, the PLA unveiled a plan to slash its land units even further, cutting the total ground force to less than one million individuals, and redistribute the remaining personnel to all other branches, including the PLAN, specifically to support operations abroad.

“This reform will provide other services, including the PLA Rocket Force, Air Force, Navy and Strategic Support Force (mainly responsible for electronic warfare and communication), with more resources and inputs, and the PLA will strengthen its capability to conduct overseas missions,” Xu Guangyu, a senior adviser to the government-funded China Arms Control and Disarmament Association, told Global Times, an official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party. “The PLA must be capable of spotting overseas threats and destroying hostile forces thousands of kilometers away before they enter our 12 nautical mile territorial waters. China’s overseas interests are spread around the world and need to be protected. These are beyond the army’s current capabilities.”

Its perhaps not surprising then that as Chinese forces make their way to Djibouti, three PLAN warships are in the process of conducting an uncommon “goodwill voyage” through the Mediterranean Sea, while a separate flotilla is moving through the area en route to joint drills with the Russian Navy. During the transit, China’s sailors practiced blasting targets at sea ahead of the upcoming Joint Sea 2017 exercise, which will take place in the Baltic Sea. Since 2005, the two countries have held seven combined naval exercises. The last of these, Joint Sea 2016, occurred in the contested South China Sea and was the first in the series to include simulated “island seizing missions.” With its African lily pad, the PLAN could step up its involvement in these European drills or even start all new unilateral, bilateral, or multinational exercises with its partners in Africa and the Middle East. Regardless, it will make it much easier for China to show its flag in general and make those appearances much more significant whenever and where ever they occur.

Potential for tensions

The PLA’s push to become a bigger player on the international scene has long worried other countries, including the United States. The establishment of a base in Djibouti in particular has only added to those concerns about potential tensions. Though small, the African country already plays host to American, French, British, and Japanese military contingents. Other countries, including Iran and the United Arab Emirates, have or are considering basing military forces in the country or elsewhere in the Horn of Africa.

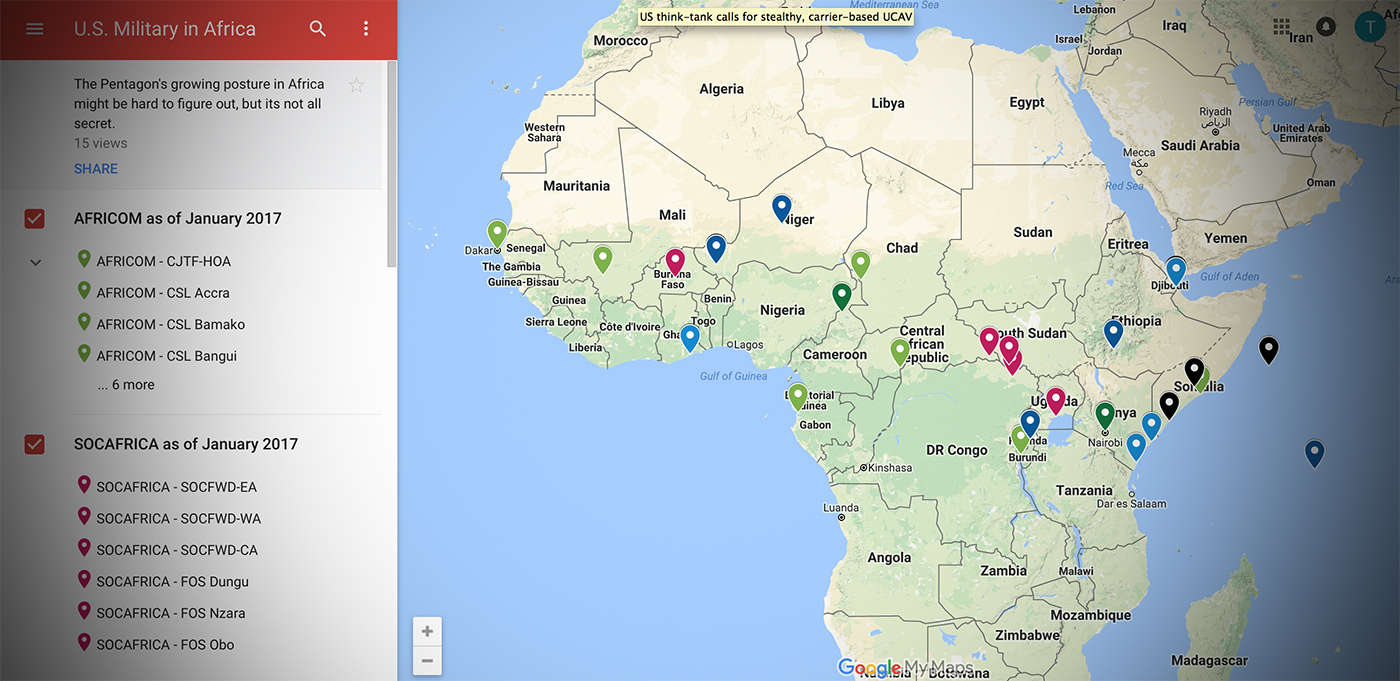

The U.S. military in particular uses Djibouti as a major hub for operations across East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula on the other side of the Gulf of Aden, something The War Zone has previously covered in depth. The ever expanding American bases at Camp Lemonnier and Chabelley Airfield have served as a staging point for drone strikes and special operations missions in both Somalia and Yemen, as well as other regional military activities. In the past year, dangers in the area for American forces have only increased, with Yemeni rebels firing cruise missiles at U.S. Navy warships and laying sea mines that could threaten both military and commercial ships. Combined with an expanding, secretive counter-terrorism campaign in neighboring Somalia, the country will undoubtedly continue to be strategically significant to the U.S. military for the foreseeable future.

And American commanders aren’t necessarily thrilled about having to run these sensitive operations in a shared space with the Chinese. The U.S. military “expressed … concerns about some of the things that are important to us about what the Chinese should not do at that location” to President Guelleh, U.S. Marine Corps General Thomas Waldhauser, head of U.S. Africa Command, told members of Congress in March 2017.

Make sure to check out our interactive google map showing U.S. military facilities across in Africa.

“We’ve never had a base of, let’s just say a peer competitor, as close as this one happens to be, so there’s a lot of learning going on, a lot of growing going on,” Waldhauser said in a separate interview with Breaking Defense. “Yes, there are some very significant operational security concerns.”

In both cases, he declined to elaborate on what those concerns were specifically. However, having Chinese personnel in such close proximity could give both parties the opportunity to spy on each other. For China in particular, it would give them a better opportunity to observe its American counterparts during actual operations. There are also concerns that authorities in Beijing could pressure Guelleh to change or even rescind the terms of America’s lease agreements, though this seems unlikely. These deals are worth millions in direct payments, as well as the economic benefits of hosting large numbers of U.S. troops and supporting contractors. Neither party would be in a hurry to willingly give up the strategic position either.

“The Bab al-Mandeb [strait between Yemen and Djibouti] is an essential maritime chokepoint from an energy, shipping and security perspective,” Dr. Geoffrey Gresh, an associate professor and Chair of the International Security Studies Department at the National Defense University, as well as author of Gulf Security and the U.S. Military: Regime Survival and the Politics of Basing, told me by Email back in 2015. “Djibouti is an important and essential gateway or doorway to the rest of Africa.”

With the Chinese now establishing their base, whatever its purpose ultimately turns out to be, that gateway is getting just a little bit more crowded.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com