The first ever attempt by the Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) system to intercept a mock intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) was been successful, according to the U.S. military’s Missile Defense Agency (MDA) and defense contractor Lockheed Martin. The long-planned test, known as Flight Test THAAD-18 (FTT-18) had taken on new significant after months of increasingly worrisome North Korean missile launches.

In its official press release, MDA did not give the exact time or location of the intercept, which occurred on July 11, 2017. Situated at Pacific Spaceport Complex Alaska in Kodiak, Alaska, a U.S. Army crew from the 11th Air Defense Artillery Brigade at Fort Bliss, which controls all the operational THAAD batteries, detected, tracked, and intercepted the surrogate IRBM somewhere over the Pacific Ocean north of Hawaii. A U.S. Air Force C-17 cargo plane air dropped the target missile during the experiment. Previous missile defense tests have also employed this air-drop method.

“This test further demonstrates the capabilities of the THAAD weapon system and its ability to intercept and destroy ballistic missile threats,” MDA Director U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Sam Greaves said in a statement. “THAAD continues to protect our citizens, deployed forces and allies from a real and growing threat.”

“With this successful test, the THAAD system continues to prove its ability to intercept and destroy many classes of the ballistic missile threat to protect citizens, deployed forces, allies and international partners around the globe,” Richard McDaniel, vice president of Lockheed Martin’s Upper Tier Integrated Air and Missile Defense Systems said in a separate press release.

Representatives of the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation, the Ballistic Missile Defense Operational Test Agency, and the Army Test and Evaluation Command were all on hand for FTT-18. In addition to the Army and the Air Force, U.S. Strategic Command’s Joint Forces Component Command for Integrated Missile Defense (JFCC-IMD) and the U.S. Coast Guard participated in the event.

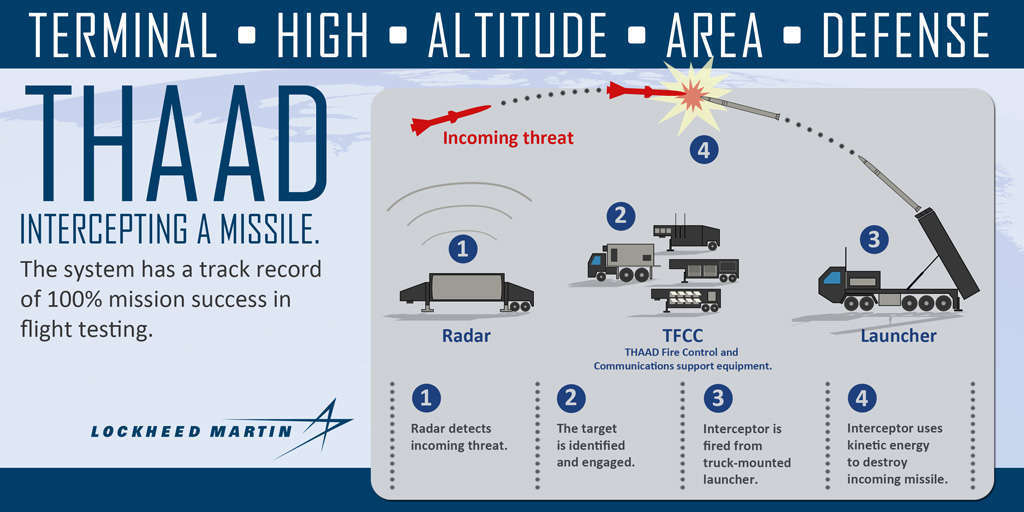

This was the first time THAAD had ever intercepted a target representing an IRBM and was the system’s 14 successful intercept since a revised testing regimen began in 2005. As intended, “the THAAD system then developed a fire control solution and launched an interceptor that destroyed the target’s reentry vehicle with sheer force of a direct collision,” according to Lockheed Martin.

“The successful demonstration of THAAD against an IRBM-range missile threat bolsters the country’s defensive capability against developing missile threats in North Korea and other countries around the globe and contributes to the broader strategic deterrence architecture,” MDA added. In March 2017, the U.S. military began deploying THAAD systems to South Korea. Among its otherwise rapidly expanding ballistic missile arsenal, the reclusive regime has at least two working IRBM types. The technical definition of this class of weapons specifies a maximum approximate range of at least 1,850 miles and no more than 3,420.

The first is the BM-25 Musudan, also known as the Hwasong-10, which has an estimated range of approximately between 1,550 and 2,485 miles. The North Koreans first successfully tested that missile in June 2016. The other is an elongated version of Hwasong-10, called the Hwasong-12, which experts believe can hit targets approximately 2,300 to 3,700 miles away. If accurate, that upper limit would actually place the weapon out of the IRBM category. North Korea demonstrated the Hwasong-12 in May 2017, the same month the U.S. military declared the first THAAD elements operational in South Korea. Both the Hwasong-10 and -12 are road-mobile, making them harder for U.S. and South Korean forces to track. On July 4, 2017, North Korea also fired a longer range intercontinental ballistic missile (IBCM), known as the Hwasong-14, for the first time.

Even after FTT-18, it is still not entirely clear how successful THAAD might be against a real IRBM threat. “Soldiers operating the equipment were not aware of the actual target launch time,” MDA’s statement noted. However, there was no indication of what other information, such as heading, flight envelope, or other factors, the personnel may have received before the test.

The War Zone has previously reported on the THAAD’s potential difficulties in shooting down an incoming ballistic missile, especially in the cramped confines of the Korean Peninsula. Most importantly, the system may be deficient against missiles flying in extremely high apogee flight profiles, which North Korea has used in testing, but which would also likely be the flight envelope for an attack on targets in South Korea or Japan. There are also concerns about the AN/TPY-2 radar’s ability to track objects outside a narrow cone, as well as the limitations of other supporting sensors. You can find our analysis of these issues in greater depth, which we wrote ahead of the launch, here. It’s also worth noting that the U.S. Army had deployed a THAAD battery to Guam in 2013, specifically to counter the BM-25, more than three years ahead of the system’s first actual test against an IRBM target.

Regardless of the results, MDA already has plans to continue testing. At present, the agency hopes to conduct the next THAAD experiment, FTT-15, sometime before the end of 2017. This launch will be focused purely on gathering data rather than intercepting a target missile, however. The Agency is planning to pit the system, along with the sea-based Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) and land-based Patriot surface-to-air missile systems, against another surrogate IRBM sometime between 2017 and 2018, as part of a test called Flight Test Operational-03 Event 2, or FTO-03 E2.

Many, even within the U.S. government, say this test schedule is too slow, especially given the pace of North Korean ballistic missile developments. “We are not going fast. We are so risk-averse that we only test every 18 months,” U.S. Air Force Gen. John Hyten, head of U.S. Strategic Command, told Stars and Stripes in an interview earlier July 2017. “The best way to build rockets, the best way to move fast, is to build it, test it, instrument it, learn from your failures,”

So, it is entirely possible that, buoyed by this success, the Pentagon may add additional tests of THAAD or other systems to its plans in the coming months in order to find and fix potential problems and make sure they are truly ready in a crisis.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com