Every year around July 4th, U.S. military units record greetings and write messages to celebrate the country’s independence. In their annual salute to the nation, members of the Vermont Air National Guard decided to share their state’s own connection to the American Revolution by holding a distinctive flag not everyone might recognize.

The 158th Fighter Wing is nicknamed “The Green Mountain Boys” after a militia that fought on the side of the United States during the Revolutionary War. In the blinding sun at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, five members of the wing and its 134th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron held up that group’s distinctive green and blue banner.

“It’s The Green Mountain Boys, live from Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar,” one of them says in the brief recording. The unit, with its F-16 Viper fighter jets, has been in the region fighting ISIS as part of the U.S.-led coalition since December 2016.

Now, of course, there were no air forces or fighter jets during the American Revolution. Officially, the 158th traces its direct lineage to the 134th Fighter Interceptor Squadron and the formal recognition of the Vermont Air National Guard in 1946. But the wing highlight’s Vermont’s unique place in America’s formative history with its moniker. The Green Mountain Boys, and their leader Ethan Allen, was an important factor in the Revolutionary War and the creation of Vermont itself.

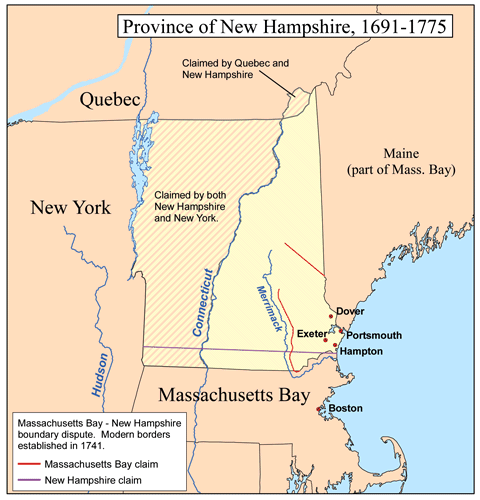

The militia and its grievances with British royal authorities actually predate the formal beginning of the colonial revolt that ultimately gave birth to the United States. In 1749, Benning Wentworth, the royal governor of what was then the Province of New Hampshire began issuing landing grants west of the Connecticut River. One had to pay to get one of these “New Hampshire Grants” and Wentworth was more interested in making money than anything else. As such, he had no qualms about allotting territory that was already claimed by individuals from the neighboring Province of New York.

The resulting land disputes became so pronounced that King George III officially stepped in and decreed that the land belonged to New York in 1764. Many of the settlers from New Hampshire were outraged at the decision, which stripped them of their property, and began an armed revolt.

Ethan Allen, his brother Ira Allen, their cousins Seth Warner and Remember Baker, and other like-minded individuals formed what became known as The Green Mountain Boys at Catamount Tavern in Bennington. Taverns were a common meeting place at the time, with similar establishments having hosted the creation of The Sons of Liberty and the U.S. Marine Corps.

The Green Mountain Boys spent the subsequent years defending their claims and harassing officials and other “Yorkers.” By the time the Continental Congress declared independence from the British Crown in 1776, New York authorities had long had warrants out for the arrest of Ethan Allen and his “Bennington mob.” But while this might have made it seem as though a union between the militia and the rebellious colonists would have been an easy decision, this was far from the reality.

Though his years of armed defiance of both authorities in New York who saw his claims as illegal and officials in New Hampshire who sought to reign in the Green Mountain Boys, Allen had alienated many on both sides. Revolutionary governments in both regions were in no rush to legitimize the group or its aspirations. As it turns out, a revolutionary force made of militia from Massachusetts and Connecticut were the first to enlist his aid as they pushed into what is today upstate New York.

Allen and The Green Mountain Boys joined the group, ultimately under the command of the infamous eventual traitor Benedict Arnold, for the assault on and capture of Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775. Afterwards, the militia made several independent attempts to seize control of Fort St. Jean in Quebec. These all failed, squeezing the force to the point that it effectively disbanded.

In June 1775, Allen and Seth Warner traveled to Philadelphia to propose the formal creation – with formal supplies and formal paychecks – of a “ranger regiment” from men in the New Hampshire Grants. The Continental Congress agreed, but effectively placed the resulting unit under the authority of New York’s new provisional government. In an apparent attempt not to upset their newfound legitimacy, the reformed Green Mountain Boys resoundingly elected Warner to lead the force, appointing Ira Allen and a third brother Herman to other important positions, but cutting the divisive Ethan out of the organization completely.

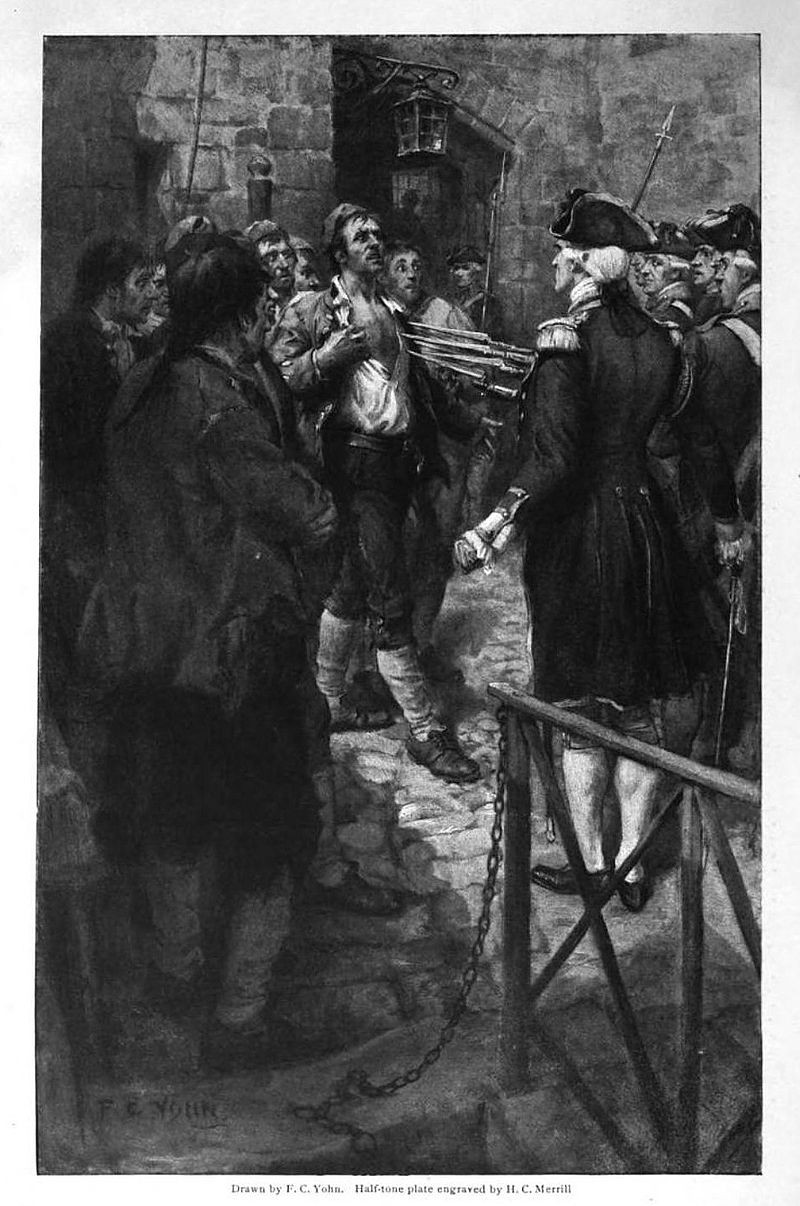

After some creative bargaining with General Philip Schuyler, head of the Continental Army’s Northern Department, Ethan Allen secured the right to accompany his men as a civilian. His ambitions quickly got the better of him and as American troops began their invasion of Canada he found himself increasingly unwelcome. Repeatedly sent out to try and rally Canadians and Native Americans to join the rebellious colonists against British rule, his hubris eventually took over and he tried to capture the city of Montreal in September 1775. Though he had the element of surprise, his company of 100 men was simply no match for the loyal defenders.

“I am very apprehensive of disagreeable consequences arising from Mr. Allen’s imprudence,” Schuyler reportedly wrote after learning of the debacle, according to Michael Bellesiles Revolutionary Outlaws: Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier. “I always dreaded his impatience and imprudence.”

Initially sent to a prison in Cornwall, Allen spent nearly three years bouncing from prison to prison after King George III decided he and other revolutionaries should be held in the colonies as prisoners of war. So, despite his previous run-ins with British officials, his sentence was relatively light as he received the substantial rights and limited parole befitting a captured officer. In May 1778, the British traded him for one of their own.

In the meantime, in January 1777, upset at their continued political limbo, a convention of individuals within the New Hampshire Grants decided to declare their own independence, separate from both Great Britain and the rebel colonists. First named the Republic of New Connecticut, the small country renamed itself the Republic of Vermont – a sort of portmanteau of the French phrase les verts monts, or Green Mountains – six months later. Despite Ethan Allen’s imprisonment and his militia’s complicated affiliation with the Continental Congress, they adopted his flag as their official symbol.

Effectively a rogue province within two rogue provinces, neither British nor continental authorities recognized the decision. And while the new government was keen to take property from individuals loyal to the Crown, they also welcomed deserters and others fleeing the conflict, becoming a sort of maroon community in the mountains. Many of the Allen family became major players in the new country’s politics and military affairs.

In 1778, Ethan Allen himself petitioned the Continental Congress to let Vermont join as an independent state. The New York delegation was especially resistant to this idea, with no amount of ongoing civil war warming them to the idea of ceding their claims to the region. In 1779, revolutionary Governor of New York George Clinton offered to drop all claims to property in New Hampshire Grants if the Vermonters would agree to accept his state’s authority over the area. Incensed at the offer and acting as lead negotiator, Allen not only flatly rejected it as an attempt “to deceive [the] woods people,” but subsequently negotiated in secret with British officials in Canada about rejoining the United Kingdom in exchange for becoming a new, separate Crown province. Those overtures, backed by generous prisoner transfers, failed to generate any support from King George III or other officials.

Allen’s treasonous actions meant that even after the new United States made peace with Great Britain in 1783, Vermont continued to operate as an independent country. The British had given up their claim to the territory, but the new U.S. government, perhaps ironically, had no intention of welcoming them into the union.

The last stanza of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem The Song of the Vermonters, 1779 highlights this fiercely independent nature:

Come York or come Hampshire, come traitors or knaves,

If ye rule o’er our land ye shall rule o’er our graves;

Our vow is recorded—our banner unfurled,

In the name of Vermont we defy all the world!

Only after his death in 1789 did the situation begin to change, though there is no indication the two events were directly connected. The next year, New York and Vermont finally settled their differences, with an agreement to reimburse New Yorkers for their claims. Vermont paid $30,000, a not significant amount at the time, and on March 4, 1791 joined the union as the 14th state. In an ominous portent of things to come, the decision was motivated in part by the need for a free state to serve as a counterweight to the proposed admission of slave-owning Kentucky.

But as the Vermont Air National Guard’s Independence Day message highlights, the state remains very proud of its brief time as an independent country, and of Ethan Allen’s and The Green Mountain Boys’ spirit of freedom. Until 1960, Burlington International Airport was actually called Ethan Allen Air Force Base. Today, the Vermont National Guard as a whole carries the Green Mountain Boys name, as well.

“I am the dream of Ethan Allen, soaring above the battlefields of the American Revolutionary War from Bennington to Fort Ticonderoga,” the first sentence of the 158th Fighter Wing’s official history proudly declares. It continues the “legacy of the original Green Mountain Boys.”

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com