When the A-10 Warthog first entered service, its primary job was standing ready to blow up hordes of tanks if the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies ever invaded Western Europe or if a similar major conflict erupted on the Korean Peninsula. Decades later, after years of flying the jets in a broader close air support role, the U.S. Air Force looked into what it would take to rent a fleet of the blunt-nosed attack jets to Colombia, where they would’ve blasted leftist guerrillas and drug smugglers.

In early November 2003, U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Randall Schmidt, then the dual-hatted commander of U.S. Air Forces Southern and 12th Air Force, traveled to Bogota, Colombia to meet with the head of that country’s air force. During their meetings, the Colombian officer broached the subject of leasing 18 A-10s for a period of between three to five years.

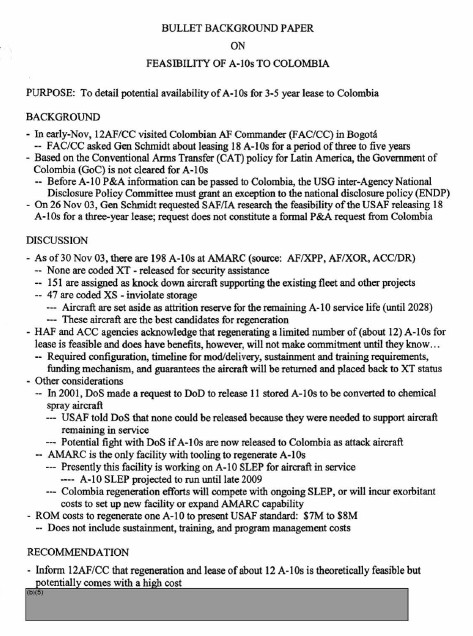

The American flag officer relayed the message back to his superiors, who determined immediately that Colombia was not presently cleared to purchase A-10s, regardless of any other issues, according to a backgrounder on the issue the service crafted sometime in the next three months. Undeterred, he asked the Air Force’s International Affairs office to look into the feasibility of the request.

The bullet background paper on the matter made it into a packet of materials the Pentagon put together for U.S. Marine Corps General Peter Pace, then the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, before a trip in February 2004 that would take him first to U.S. Southern Command’s headquarters in Miami, Florida, then on to Colombia, and finally to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba on the way back. The Department of Defense released the full collection of documents, many of which it heavily redacted, in response to another individual’s Freedom of Information Act request. The records are now publicly available online.

At the time, Colombia was still heavily engaged in a long-running civil war with a collection of leftist rebels, most notably the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, better known by their Spanish acronym FARC. On top of that, the country’s security forces were battling drug cartels that had taken advantage of the conflict to establish their operations in areas with little or no government control.

In the early 2000s, to support government operations against both of these groups, the Colombian Air Force relied on American A-37 Dragonfly and OV-10 Bronco light strike aircraft, as well as Israeli Kfir fighter jets. Colombia had also upgraded a number of aging C-47 transports into turboprop gunships, which it called AC-47T Fantasmas, or “ghosts.” In 1993, the United States reportedly rejected a request to buy a number of larger and more capable AC-130 gunships. Armed helicopters provided additional firepower for mobile operations in the country’s remote jungles.

But FARC rebels had access to heavy weapons, including large caliber machine guns, and were finding ways to obtain man-portable shoulder-launched surface-to-air missiles. These weapons, combined with the rugged terrain and dense foliage, which helped hide insurgent and criminal movements and base camps, posed a significant threat to the country’s aircraft. Already combat proven over the skies of Kuwait and Iraq and able withstand an amazing amount of punishment and weave precision fire through dense jungle canopy, the venerable A-10 would have been a welcome addition. And after an American-led coalition invaded Iraq in March 2003 to unseat dictator Saddam Hussein, the Warthogs again became a star of a major U.S. military operation. Colombian Air Force officials would have undoubtedly seen the routinely glowing public reports about the aircraft’s performance in the Middle East.

Schmidt found that there was tentative support for the rental idea from both the Air Force’s top leadership and the head of Air Combat Command (ACC), which controlled the bulk of the service’s combat-coded aircraft, including all of the active duty A-10s. “Regenerating a limited number of (about 12) A-10s for lease is feasible and does have benefits,” the bullet background paper noted. Unfortunately, there were significant bureaucratic hurdles in the way.

The most immediate issue was that ACC, perhaps surprisingly given its relationship with the low- and slow flying Warthogs, was not interested in giving up a squadron of its own aircraft to Colombia. With the straight-wing, twin-engine jets long out of production, Air Force officials asked about what was baking in the sun out at the famous boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona.

What they heard back was that 198 A-10s were sitting the desert in various states of disrepair and none that were coded “XT” or “released for security assistance.” A total of 151 were set aside as parts sources to help sustain the Air Force and Air National Guard fleets, as well as any other project that might require Warthog parts. The other 47 were “XS” or in “inviolate storage.” Also known as Type 1000 storage, planes in this category are ready to return to duty with a minimum amount of effort. The Warthogs in this condition at the Boneyard were specifically on hand as a reserve in case there was a sudden need for replacement aircraft or a surge in demand for spare parts.

Still in relatively good shape and with most of their pieces still in place, they were also the best candidates for rehabilitation and transfer to Colombia. The Air Force’s top brass and ACC refused to commit to letting any of those aircraft out of storage until there was a clear understanding and commitment on the part of the Colombians with regards to “required configuration, timeline for modification]/delivery, sustainment and training requirements, funding mechanism, and guarantees the aircraft will be returned and placed back to XT status,” the backgrounder explained. The last stipulation appears to be a typo. The Air Force would almost undoubtedly have wanted the jets to go back into XS storage and not get a new XT status after coming back from their Latin American tour of duty.

In addition, the Air Force worried that the effort required to get these A-10s combat ready again would compete with separate upgrade work on its own Warthogs. At the time, the Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Center (AMARC) at Davis-Monthan – now known as the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG) – had the only facility with the necessary tooling to do depot-level maintenance on the jets.

The only way to adequately support both efforts would be to “incur exorbitant costs to set up new facility or expand AMARC capability,” the Air Force complained. It would already take between $7 and $8 million to just regenerate each aircraft bound for Colombia. In addition, someone would have to pay for other tasks such as training Colombian pilots to fly them and sustaining the planes in country.

On top of all that, there was one last impediment to the plan that no amount of money would have been able to solve. The Air Force was deathly worried about getting into a fight with the State Department, and not over export restrictions or human rights concerns – though American diplomats would certainly have needed to do a certain amount of finessing on both those issues.

No, the big problem was that in 2001, State had asked the Pentagon for 11 A-10s to support its own counter-narcotics programs in Latin America, including Colombia. Faced with many of the same dangers as the Colombian Air Force, the Department had similarly come to the conclusion that it needed more rugged planes to spray herbicides on illicit drug crops. The Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, better known by its acronym INL, had already bought armored crop dusters and modified OV-10 Broncos that offered better protection against enemy fire. They had even considered purchasing armed versions to escort the spray aircraft. But the A-10 would have dramatically increased the capability of the Bureau’s Air Wing.

The Air Force balked at the idea, saying every one of the A-10s in the Boneyard was essential to maintaining its own fleet of aircraft. “Potential fight with DoS [Department of State] if A-10s are now released to Colombia as attack aircraft,” the background paper warned.

Ultimately, the service’s top leadership went back to Schmidt with at least two recommendations. The first one was that “regeneration and lease of about 12 A-10s is theoretically feasible but potentially comes with a high cost.” The other recommendation or recommendations are redacted. This is the only portion of the one-page document government censors blacked out.

We may never know what the other reasons were, or whether they argued for or against sending the A-10s to Colombia. We do know the lease plan never materialized. Instead, Colombia subsequently purchased a fleet of Embraer EMB 314 Super Tucano light attack aircraft. In 2013, The Washington Post reported that the Central Intelligence Agency and other members of the U.S. Intelligence Community were actively supporting Colombian targeted strikes against FARC leaders and other rebels. The project reportedly included integrating the GBU-12/B laser-guided bomb onto older Colombian A-37B Dragonfly light attack jets.

In general, these single-engine turboprops have become popular with small air forces around the world for surveillance and counterinsurgency missions, as well as basic training. The United States itself has facilitated their sale to Afghanistan and Lebanon and the Air Force is planning to include them in an experimental light attack fly-off later in 2017.

And in an interesting twist of fate, in August 2016, Colombian pilots brought some of their Super Tucanos to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana to take part in a Green Flag East training exercise. During the practice sessions, they flew with Air Force A-10s from Moody Air Force Base. We don’t know if any of those Colombian aviators were aware of the discussions more than a decade earlier that might’ve had them flying the Warthogs themselves.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com