Though Russian officials have delayed plans to move forward with two of its major surface ship programs indefinitely, including a new aircraft carrier, the Kremlin insists it will move ahead with work on a modern amphibious assault ship. Despite assurances to the contrary, there is little evidence that the country’s shipbuilding infrastructure is anymore ready for this task, and the project could easily end up deferred in the face of other priorities.

On June 4, 2017, Russia’s state-owned news outlet Sputnik reported that the Ministry of Defense had included the proposed Lavina-class amphibious assault ship in its up-coming modernization plan, which will run through 2025. In 2015, the Krylov State Research Center in St. Petersburg unveiled the design along with that of the highly ambitious Project 23000E Shtorm aircraft carrier.

Krylov “has conducted extensive studies on the creation of a next-generation universal amphibious assault ship design,” Valery Polovinkin, an advisor to the firm’s general director, told Zveda television, which the Russian ministry of defense operates. The ship would be more capable than the French Mistral-class, which Russia had previously attempted to buy, he added.

On paper, the 24,000 ton Lavina – which means “avalanche” in Russian – displaces 2,500 tons more than the Mistral class. Though it’s not clear whether it will be conventionally or nuclear-powered, Krylov claims its ship will be able to make 22 knots, three knots faster than its French counterpart. Given Russia’s capacity to produce large conventional marine engines, or lack thereof, the proposed ship would most likely need a nuclear powerplant for this to be true.

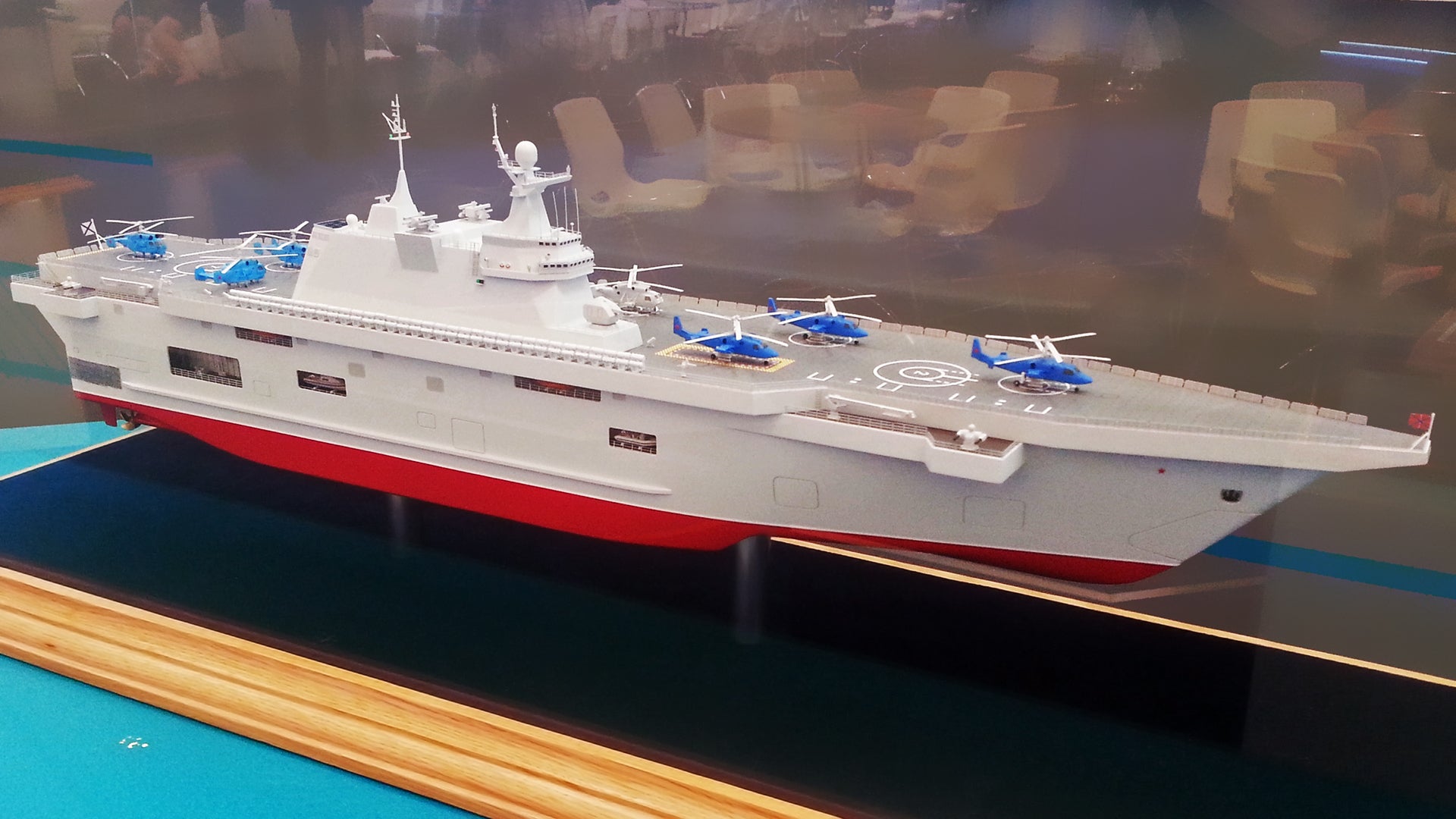

Krylov designed the amphibious ship to carry up to 50 main battle tanks and other armored vehicles, depending on their size, along with 500 troops. Between four and six Project 11770 or Project 02510 landing craft would ferry these forces ashore during an assault. A model the company showed off in 2015 featured a turret with a 100mm gun, two Pantsir-M surface-to-air missile launchers, and three Palash close-in weapon systems for self defense.

But by far, the Lavina’s most powerful weapon would be its compliment of up to 16 helicopters, including some number of the advanced Ka-52K Katran, a navalized version of the Ka-52 Alligator gunship. In addition to folding rotor blades and other features for shipboard operations, the new version can carry the Kh-31 and Kh-35 supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles. “This is the first helicopter in the world capable of using the Kh-31 and Kh-35 anti-ship cruise missiles,” Zveda reported, according to Sputnik.

On top of that, the attack helicopters have a 30mm cannon and can carry laser-guided Vikhr anti-tank missiles, R-73 short-range air-to-air missiles, unguided rockets, and other weapons. There are somewhat questionable reports that Kamov is looking to integrate the long-range R-77 air-to-air missile, an analogue to the American AIM-120, onto the choppers. The Katran’s does have a nose-mounted radar, along with the option for a mast-mounted type, for air- and surface search functions, along with infrared video cameras.

Russian officials have already been buying the Ka-52K, initially expecting to deploy them on its now canceled

Mistrals. This deal, which U.S. officials had already criticized and pressured their counterparts in Paris to reconsider, finally broke down completely after the Kremlin invaded Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014. France subsequently refunded a significant amount of money it had already received for the project and then sold the two ships it had already under construction to Egypt.

But there’s still no clear evidence that Krylov, or any of Russia’s other shipyards, have the capacity or knowledge base to produce a ship like the Lavina. Since 2004, the Yantar Shipyard, located in Russia’s Kaliningrad enclave on the Baltic Sea, has been struggling to finish orders for two significantly smaller Ivan Gren-class landing ships. These 6,000 ton ships can carry 13 main battle tanks or 36 armored personnel carriers, as well as 300 troops, but have no flight deck or helipad. Yantar laid down the hull of the Ivan Gren in 2004, but didn’t launch her until 2012. The vessel began sea trials in 2016. The Russian Navy expects to get the second ship, Petr Morgunov, sometime this year.

Krylov has never built an aircraft carrier or an amphibious assault ship in its history. The firm insists that, despite it turning into a debacle, the technical data Russia obtained from the Mistral arrangement has given it the knowhow, especially in the design of well decks for amphibious operations, to proceed with the project. As part of the deal with France, the conglomerates behind Mistral – STX Europe and DCNS – agreed to share a certain amount of information with Russian engineers as part of a planned joint venture that would have produced additional ships in Russia.

The two ships that France intended to sell to Russia, but ultimately offered to Egypt, did have changes based on Kremlin requirements. Given Moscow’s rapidly warming relationship with Cairo, it is possible that Russia may be able to learn even more about the design in the end. The two countries are already in talks regarding the sale of Ka-52Ks specifically for these warships.

“The carriers [the Mistrals] had been built in accordance with Russian requirements and for Russian systems,” Alexander Sitnikov, an independent analyst and frequent commentator on military issues for Sputnik, said in an interview earlier in 2017. “Rebuilding them to NATO standards was technical feasible, but not commercially justifiable: it would be cheaper to simply scrap them. If Russia wins the tender for the helicopters for the Mistrals (and the probability is very high), Egyptian experts will allow Russian naval engineers access to all the ships’ systems.”

There’s still no guarantee that any amount of information will translate into actual capacity to build the ships, which would require a skilled workforce and significant improvements to Russia’s shipyard infrastructure. As we have written at The War Zone many times before, those factors are largely separate issues dictated by Russia’s economy. In 2015, the Nevsky Design Bureau, proposed a smaller, competing 14,000-ton design, called the Priboy, or “surf.” So far, this ship has failed to materialize, too.

If all goes to plan, the Russian Navy hopes to get its first Lavina-class ship before 2025. But previous delays in similarly sized ships and persistent economic factors suggest this may be an optimistic time frame.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com