The U.S. Navy has finally gotten the first of its latest class of supercarriers, the future USS Gerald R. Ford. Though the service expects to commission the ship within months, there are still significant questions about when it will be fully operation and what exactly that will really mean in the end.

On May 31, 2017, Newport News Shipbuilding delivered the upcoming Ford to the Navy’s own facilities in Newport News, Virginia. This is the service’s first all-new carrier type in more than four decades and the first new flattop of any kind – not counting the USS America, technically an amphibious assault ship – it has received since what became the Nimitz-class USS George H. W. Bush arrived in 2009. The Navy originally expected her to join the fleet in March 2016.

“Over the last several years, thousands of people have had a hand in delivering Ford to the Navy – designing, building and testing the Navy’s newest, most capable, most advanced warship,” Rear Admiral Brian Antonio, the Navy’s program executive officer for aircraft carriers, said at a ceremony marking the milestone. “It is because of them that Ford performed so well during acceptance trials, as noted by the Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey.”

Antonio’s not wrong about the ship’s design being a significant departure from the existing Nimitz-class. Compared to the older ships, the Ford-class’ nuclear reactor and associated generator turbines produce more than three times as much electricity. This is vital to run a host of new systems, including high-tech battle management networks and other computer systems, long-range radars and other sensors.

But by far, most important are the ship’s electrically-powered Electromagnetic Aircraft Launch System (EMALS) and Advanced Arresting Gear (AAG). Nimitz-class carriers launch aircraft using steam-powered catapults and recover aircraft with a hydraulic arresting system. On paper, both systems should allow the ship’s crew to have more control over how they get aircraft into the air and get them back on the deck, speeding up the processes and reducing wear and tear on the ship and the planes. The Navy has made a somewhat questionable claim that the Ford-class will be able to increase overall sortie generation rates by about a third compared to the older carriers. The precision equipment could also fundamentally change the way people design carrier-based aircraft, paving the way for smaller, lighter drones and other developments.

The only problem is that neither of these systems work reliably in their present form. The technology is revolutionary, but still largely unproven, even after many years of research and development and huge sums of money invested. Without them performing as expected, the Ford and its sister ships will simply be incapable of doing their job to any meaningful degree. The War Zone’s Tyler Rogoway, who has been following the development of the new supercarrier, highlighted this issue earlier in May 2017:

The thing is, both of these components are absolutely critical to the carrier’s mission and are heavily integrated into the vessels. Also they don’t have to work reliably just some of the time, but all of the time. Aircrew’s lives are literally depending on them as is the carrier’s actual war fighting ability. So if they are not able to function in a highly reliable manner, it equals a mission kill for these massive ships.

In April 2017, given the issues with Ford, Rogoway offered his own detailed recommendations of how the Navy could right-size its carrier forces, as part of a larger set of proposals for future naval developments.

The Navy is well aware of these issues. In August 2016, Bloomberg.com obtained a memo Frank Kendall, then Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics and effectively the Pentagon’s top weapons buyer, sent to Ray Mabus, who was then Secretary Navy. In his notice, Kendall said he was ordering an independent review of the program, which had already seen serious cost overruns and seemed destined for more in order to fix the glaring issues with its most central equipment. He specifically mentioned trouble with the EMALS and AAG, but also pointed to persistent issues with the ship’s powerplant, its dual band radar, and the ship’s elevators that take aircraft and weapons up from the hangars onto the flight deck.

“With the benefit of hindsight, it was clearly premature to include so many unproven technologies in the Gerald R, Ford,” Kendall explained. “What we have to determine now is whether it is best to stay the course or adjust our plans, particularly for future ships of the class. The first step in that process has to be a completely objective and technically deep review of the current situation.”

Though Kendall mentioned a purchasing method called “transformation,” what he really appeared to be talking about was a process known as “concurrency.” Under this concept, rather than finalizing the design of a weapon system first, the Pentagon would hire contractors to start building examples immediately while that work was still ongoing. In theory, the “concurrent” work would save time and money as “minor” fixes are applied to finished products and those still on the production line. In practice, the results have been exactly the opposite, with costly and complex changes routinely leading to delays and limiting the system’s initial combat capability.

So, in referring to this revelation as “hindsight,” Kendall may have been being very generous to himself and his colleagues. The Pentagon and the Navy had both downplayed many of these issues for years beforehand, in the face of assessments and cost estimates from both independent government watchdogs and Newport News Shipbuilding itself. In October 2015, the Government Accountability Office hit the Navy with a scathing report on the progress of Ford, titled “Poor Outcomes Are the Predictable Consequences of the Prevalent Acquisition Culture”– essentially “we told you so.”

“In July 2007, we reported on weaknesses in the Navy’s business case for the Ford-class aircraft carrier,” Paul Francis, the GAO’s Managing Director of Acquisition and Sourcing Management, explained to the Senate Armed Services Committee on Oct. 1, 2015. “Today, all of this has come to pass in the form of cost growth, testing delays and reduced capability – in other words, less for more.”

The Navy initially estimated Ford would cost $10.5 billion. GAO felt this was around $2 billion short, a number that closely matched Newport News’ own calculations. This shipyard has a wealth of experience in what goes into building carriers, having been involved in constructing every class of flattop the Navy has operated since the 1950s. It seemed the height of pique for anyone in the U.S. military to disregard the company’s view of the matter. As of 2016, the final price tag had risen to more than $13 billion, and that does not include research and development costs, which were billions more.

So, with the Pentagon’s review still ongoing, and EMALS and AAG, along with other systems, still slogging through development, its entirely unclear how long it will be before the Navy can actually put Ford to any use. Buried in its own announcement is a tactic admission of this fact: “Planned deferred work will be performed [after commissioning], and any deficiencies identified during trials will be addressed during in-port periods.”

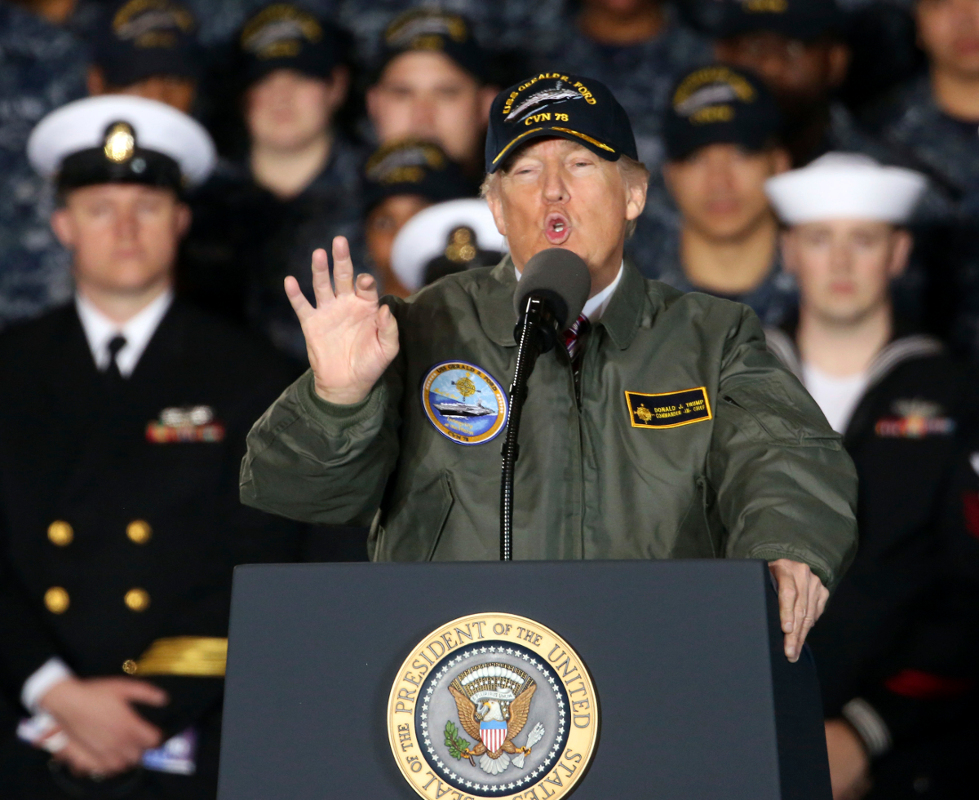

The Navy wants the ship to be combat ready by 2020, but on how significant the changes and fixes are, this may turn out to be as overly optimistic as the ship’s cost. Changes in the EMALS system in particular could potentially require a redesign of the ship’s basic profile or internal arrangement, not the kind of thing contractors could do during a brief port visit. A more drastic change, such as going back to a traditional steam catapult system – which no American company currently makes – would be even more time and labor intensive. That shift is unlikely to happen, but President Donald Trump did highlight it as a possibility in a freewheeling speech from the deck on the ship earlier in May 2017.

“You going to goddamned steam,” he said he told a Navy officer after learning about the electromagnetic catapult’s troubles. “The digital costs hundreds of millions of dollars more money and it’s no good.”

The need for expensive overhauls might not be linked to any particular system, either. The Navy repeatedly attempted to delay critical shock tests, which the Pentagon conducts on all new ships to see how they and their on board equipment might fare when things start exploding nearby in combat. Ford needs to pass those trials before it can enter service. Any one has to wonder how legitimate any such results might be if gear like the EMALS is still not fully functional under optimal conditions.

This is all on top of the normal teething trouble any new weapon system experiences, too. Workers will undoubtedly find things they didn’t even know were a problem as they put Ford through the paces before its commissioning. All of this could impact the final cost of the second Ford-class ship, the future USS John F. Kennedy, which is already under construction at Newport News.

As it stands now, unfortunately, the Navy still has a number of hurdles to overcome before it can get its newest supercarrier into action and it likely doesn’t even know yet how extensive the work required will be in the end.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com