Whenever someone retires, it marks the end of an era in their personal life. When U.S. Air Force Chief Master Sergeant Rob Wellbaum leaves the service he’ll end an entire era of aerial combat as America’s last bomber tail gunner.

On May 12, 2017, Wellbaum retired after three decades in the Air Force. When he first joined up in 1987, the non-commissioned officer had signed up for Specialty Code 111X0—Aerial Defense Gunner.

“I went into the recruiter’s office and asked them what jobs they had for enlisted [personnel] to fly,” Wellbaum recalled in an interview. “My recruiter listed off loadmaster, boom operator, and B-52 aerial defensive gunner. The gunner job sounded like the coolest job out of the three so that is what I applied for.”

For the next five years, he served in that role on a B-52 Stratofortress bomber. This aircraft – more lovingly referred to as the Big Ugly Fat Fellow, or BUFF – was the last in service to even have a tail gun.

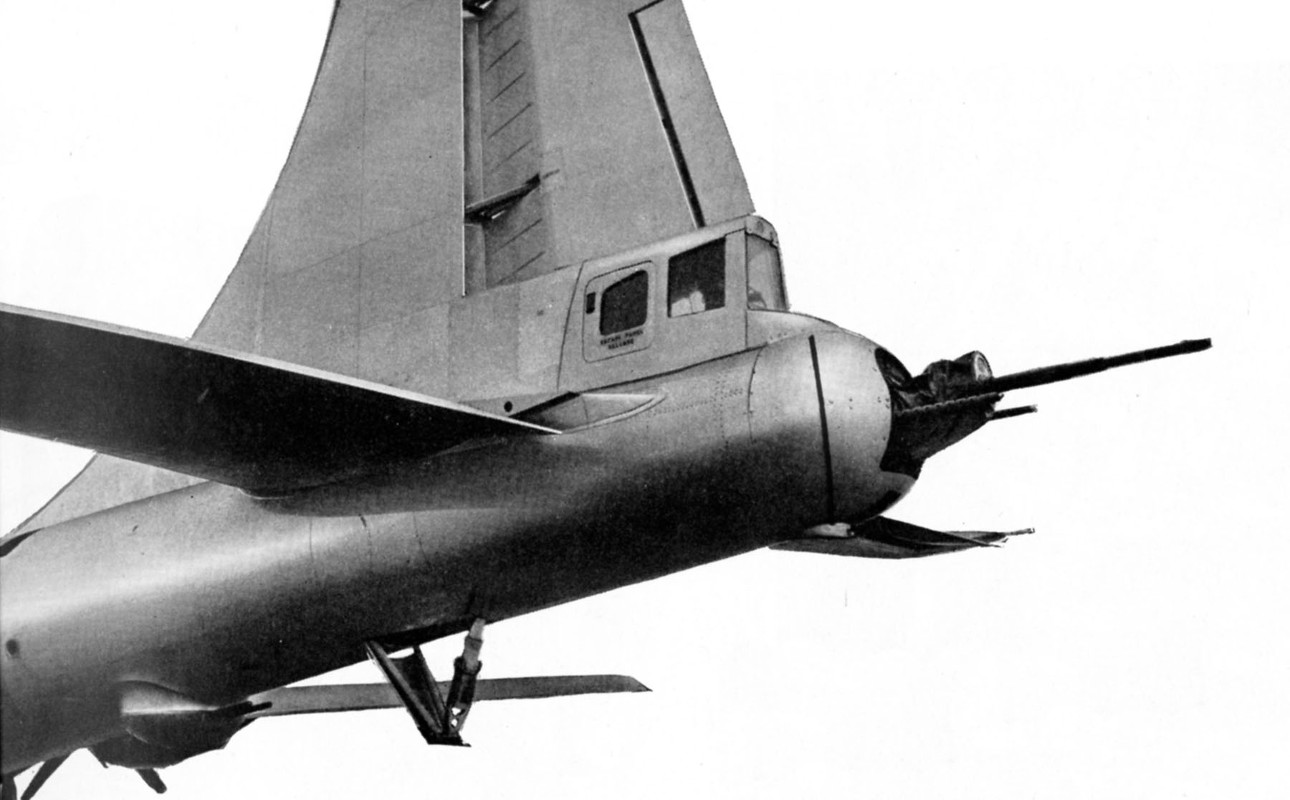

When the first B-52 prototype rolled out of Boeing’s plant in Seattle in 1952, aircraft defensive armament was already in a period of flux. For more than a decade at that point, American heavy bombers, as well many smaller attack and maritime patrol aircraft had featured various guns for self-protection against enemy fighters and interceptors.

The American workhorses of World War II, Boeing’s B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated’s B-24 Liberator both bristled with machine guns by the end of their service life. Both companies specifically designed the armament configurations to provide maximum coverage. So, in addition to weapons in the nose and sticking out the sides and the top and bottom of the fuselage, another gunner’s position was installed in the tail. From there a member of the crew could cover the vulnerable rear flank.

The U.S. Army Air Force’s entire bomber doctrine revolved around this defensive armament. The lumbering aircraft would fly together in tight “boxes” in order to provide mutually supporting firepower. U.S. military proponents of heavy bombing felt this method of operation, combined with superior aircraft designs, might even obviate the need for escorting fighter planes altogether.

The World War II experience in both the Europe and Pacific theaters showed this notion was a pipedream. Over Germany especially, American crews suffered horrific losses until sufficient escorting aircraft became available. After one raid on Nazi factories in Schweinfurt on Oct. 14, 1943, the Eight Air Force effectively lost more than 25 percent of its entire force.

“With the Schweinfurt missions went the virtual end of the idea that the heavy bomber could ‘go it alone’,” according to one 1955 Air Force history. “The debate that had continued since the early 1930’s was now all but over.”

Though this didn’t stop bombers from carrying weapons, it did begin to reduce crews’ reliance on their own guns for self-defense. Boeing’s B-29 Superfortress, which became iconic of the fight against the Japanese, still had multiple machine gun positions, including then state-of-the-art remote control dorsal and ventral turrets. Its particularly deadly tail gun position, often referred to as the plane’s “stinger,” packed a pair of .50 caliber M2 machine guns flanking a single 20mm M2 cannon. But with the Japanese Army and Navy air arms all but crushed, American crews began leaving some or all of those weapons back at base to reduce weight and increase flying time.

Many immediate post-war bomber designs for the brand new, separate Air Force continued to come with full suites of defensive weapons. The B-50, a suped-up B-29, had the same gun positions. The initial prototypes of Consolidated’s massive B-36 Peacemaker had numerous, retractable remotely-operated turrets with 20mm cannons, along with a tail gun.

But technological advances were making much of this obsolete. Most importantly, surface-to-air and air-to-air missiles gave anti-aircraft teams on the ground and fighter pilots the ability to attack bombers from increasingly long distances, well outside of the range of a bomber’s guns.

So, Boeing’s B-47 Stratojet and B-52 both dispensed with guns in the nose and fuselage completely. On both aircraft, tail guns were the only traditional defensive weapons. Nearly all of the B-52 variants featured a radar-assisted tail position with four M3 machine guns, each firing at a rate of 1,200 rounds per minute. The ultimate version, the B-52H, came with a single 20mm M61 Vulcan cannon, able to spit out up to 100 shells every second, in their place. In addition, the air search radar for the guns was powerful enough to act as a navigational aid and help keep bombers in formation, according to an article in Air Force Magazine. On top of that, it could help guide trailing bombers in a single cell toward their destination through bad weather.

Still, physically separated from the rest of the crew at the other end of the plane’s enormous fuselage, it sounds like it would have been a lonely job. However, starting with the B-52G, the gunner joined the rest of the crew in the main cabin. The Air Force Magazine piece explains this was done in order to allow the crew to better coordinate during the flight and finally put the gunner in an ejection seat like everyone else, but “many gunners rued the loss of their wide-screen view.”

Convair’s super-sonic B-58 Hustler had a similar arrangement with a single Vulcan cannon. At the same time, electronic countermeasures and chaff to jam and confuse enemy radars, along with bright-burning flares to distract heat-seeking missiles, increasingly became the primary means of defense.

Fast-forward to the 1970s and the B-52 was Americans sole remaining heavy bomber. It was also the service’s last aircraft to even feature a tail gun, whatever its utility might have been at that point. Over Southeast Asia, B-52D bombers scored just two kills. Both instances occurred over North Vietnam in 1972.

“When the target got to 2,000 yards, I notified the crew that I was firing,” Airman 1st Class Albert Moore, who was responsible for the second kill, explained later. “I fired at the bandit until it ballooned to three times in intensity then suddenly disappeared from my radar scope at approximately 1,200 yards, 6:30 low. I expended 800 rounds in three bursts.”

A gunner in another nearby B-52 confirmed Moore had blasted a North Vietnamese MiG-21. This was the last time a tail gunner from any air force scored a kill.

“On the way home I wasn’t sure whether I should be happy or sad. You know, there was a guy in that MiG,” Moore wrote afterwards. “I’m sure he would have wanted to fly home too. But it was a case of him or my crew. I’m glad it turned out the way it did. Yes, I’d go again. Do I want another MiG? No, but given the same set of circumstances, yes, I’d go for another one.”

The bomber Moore served on, nicknamed Diamond Lil and with the tail number 55-083, continued to serve until 1983. It now sits near the north entrance to the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Moore died in 2009.

After the Vietnam War ended, the Air Force continued to train enlisted personnel like Chief Master Sergeant Wellbaum to man the guns on the remaining B-52s. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the service finally decided it wasn’t worth the trouble.

“My decision to eliminate the guns from the ‘BUFF’ was not an easy one,” General George L. Butler, then head of Strategic Air Command (SAC), wrote to the aerial gunner community in the fall of 1991. “It stemmed from the collapse of the soviet threat and the leading edge of very sharp budget cuts… Our Air Force is going to go through a lengthy period of turmoil as we adapt to a dramatically changing world.”

By 1992, the Air Force had removed the guns from all its remaining B-52Gs and Hs. The service’s 111X0s, including Wellbaum, transitioned to other jobs. Neither the B-1 Bone nor the B-2 Spirit bombers ever had tail guns.

“We knew something was in the works but we weren’t expecting to be cut,” Wellbaum said of the Air Force’s decision to remove the BUFF’s weapons for good and eliminate tail gunners. “However, the Air Force did take care of us and opened up a lot of AFSCs, one of which was flight engineer.”

In total, Wellbaum accumulated more than 1,000 flight hours as a B-52 tail gunner. His last position was as the superintendent of the 15th Operations Group, the flying component of Pacific Air Force’s composite 15th Wing, which is situated at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii.

Update 5/16/2017: Since this story was published, multiple readers have reached out to inform us that there are in fact other former aerial defense gunners still on duty. Initially, it appeared as if the 15th Wing’s public affairs office had only been referring to individuals within the active component and not counted personnel who had gone on to serve in the Air National Guard. However, a representative of the Air Force Gunners Association explained that there were in fact at least two of its members still in active component units. It’s unclear how the error occurred, but it seems safe to say that the last B-52 gunner still has yet to leave the service.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com